Surprise – noun — a completely unexpected occurrence, appearance, or statement.

* * *

Unsurprisingly, there’s been some research done on the science of surprise. I read this summary on Melissa Hughes’s blog.

There is science in surprise. Neuroscientists have discovered that surprise is one of the most powerful human emotions. As it turns out, the brain’s pleasure center (or the nucleus accumbens) lights up like a Christmas tree when you experience something that you didn’t expect. Not only do you get a nice boost of dopamine, the brain releases noradrenaline – the neurotransmitter responsible for focus and concentration. Think of it as the reset button for the brain. It actually stops all of the other brain activity to let you find meaning in the surprise.

An article on sciencedaily.com highlights the work of neuroscientists Dr. Gregory Berns and Dr. Read Montague who ran experiments that used functional magnetic resonance imaging to measure changes in human brain activity in response to a sequence of pleasurable stimuli, in this case, fruit juice and water.

“Until recently, scientists assumed that the neural reward pathways, which act as high-speed Internet connections to the pleasure centers of the brain, responded to what people like,” said Montague.

“However, when we tested this idea in brain scanning experiments, we found the reward pathways responded much more strongly to the unexpectedness of stimuli instead of their pleasurable effects.”

Given this data, maybe we authors should look closely at the element of surprise in our works. If we can cause the reader’s brain to suddenly experience a pleasurable shot of dopamine, we will have captured their attention and their loyalty.

* * *

“Mystery is at the heart of creativity. That, and surprise.” — Julia Cameron

* * *

When we read a mystery novel, we expect to be surprised. All those twists and turns are designed to keep our attention. When the shy, gentle woman suddenly pulls a gun out of her purse, or the disconnected nerd leaps into the line of fire to save a stranger, we love it.

According to an essay on thenetwriters.com,

The importance of surprising your readers should never be forgotten by any aspiring writer. In fact, it should always be considered a vital part of a storyteller’s toolkit. By seeking to confound your audience with plot twists, subverting the reader’s expectations with ‘the element of surprise’ can often allow you to heighten dramatic tension in your story, add suspense, or introduce humour.

Mystery readers, though, are a fairly sophisticated bunch. Most dedicated mystery readers have a sense of the story. We’re accustomed to surprises in the form of strange clues and red herrings to distract us from figuring out who the real culprit is. Complex twists and turns are part of a good mystery, but readers know that no matter what surprises or unusual events are thrown at the amateur sleuth, she will eventually solve the mystery and save the day.

However, I read a book recently that took a couple of turns I didn’t expect. (Note: spoilers in the paragraphs below.)

* * *

Trent’s Last Case by E.C. Bentley was published in 1913 and is widely respected as one of the first, if not the first, modern detective novel. Agatha Christie called it, “One of the best detective stories ever written.” It was dedicated to Bentley’s friend G.K. Chesterton who encouraged him to write it and, maybe unsurprisingly, called it, “The finest detective story of modern times.”

The story begins when the body of a very unlikeable financial magnate, Sigsbee Manderson, is found by one of his servants, and there is concern that his death might shake up the financial markets When the editor of an influential newspaper hears of the probable murder, he calls on the charismatic Philip Trent, an artist who is also a freelance reporter and amateur sleuth, to help solve the case. Highly respected by the police authorities, Trent seems to have the intellectual acuity of Sherlock Holmes since we’re told nothing can escape his astute powers of observation. (It turns out this is an intended comparison.)

There are the usual suspects in the case: the beautiful widow, the unhappy uncle, and various others who had reasons to do away with the unpleasant Mr. Manderson. And there is an abundance of strange clues to keep the reader busy trying to put the puzzle together. Not to worry, though. Trent puts his considerable analytical skills to work and comes up with a brilliant theory that satisfies all the clues. The only problem is that he has fallen in love with Manderson’s widow, and he believes she was having an affair with one of her husband’s employees who subsequently murdered Manderson.

Trent writes his dispatch to the newspaper editor but doesn’t send it. Unwilling to implicate the woman he loves, he gives the dispatch to the widow, leaves the site of the crime, and accepts a freelance reporting assignment in another country..

Surprise #1: Trent’s solution to the mystery comes just a little after the midpoint in the book. That threw me since I’m accustomed to the reveal coming in the last chapter. I read on, curious to see how the author would continue the story. Will the widow turn out to be a scheming murderer who hunts down Trent and kills him? Will she and her lover taunt Trent with his unwillingness to accuse them?

Several chapters later, we discover:

Surprise #2: The widow wasn’t involved. Trent was wrong.

Very clever, Mr. Bentley. You led me down the garden path, convinced that Trent could not make a mistake because he was modeled on the extraordinary Sherlock Holmes.

It turns out E.C. Bentley was not a fan of Sherlock Holmes, and he intended Trent’s Last Case to show the amateur sleuth as a fallible human, not a flawless reasoning superhero. But I didn’t know that when I began reading the book, and my expectations set me up for a few surprising plot twists.

There are a couple of other surprises in the book, but I won’t reveal them here in case anyone wants to read the story. Even though Bentley employs an early 20th-century style of writing that is no longer popular, the story is enjoyable and stands the test of time.

* * *

“I love surprises! That’s what is great about reading. When you open a book, you never know what you’ll find.” –Jerry Spinelli

* * *

An interesting postscript: I uploaded this post to the TKZ site last week. Over the weekend, my husband and I had lunch with a fellow author who was telling us about a book he recently read: Fade Away by Harlan Coben. Although I hadn’t said anything about my TKZ post, our well-read friend said the thing he loved about the book was that it held many surprises. So there you have it. The proof is in the pudding.

So TKZers: Have you read Trent’s Last Case? What books have you read that took you by surprise? How do you include elements of surprise in your books?

* * *

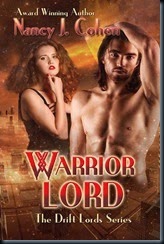

Private pilot Cassie Deakin is in for a string of surprises when she lands in the middle of a murder mystery. Even Fiddlesticks the cat takes on a new persona that’s shocking.

Private pilot Cassie Deakin is in for a string of surprises when she lands in the middle of a murder mystery. Even Fiddlesticks the cat takes on a new persona that’s shocking.

Buy on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Kobo, Google Play, or Apple Books.