@jamesscottbell

I was a student in one of the best film studies programs in the country during the golden age of American movies. The 1970s saw an explosion of great independent films and directors, many of whom were picked up by major studios. Up at U.C. Santa Barbara, our intimate band of film majors got to sit around talking with exciting new directors like Martin Scorsese, Robert Altman, Lina Wertmuller and Alan Rudolph.

I was a student in one of the best film studies programs in the country during the golden age of American movies. The 1970s saw an explosion of great independent films and directors, many of whom were picked up by major studios. Up at U.C. Santa Barbara, our intimate band of film majors got to sit around talking with exciting new directors like Martin Scorsese, Robert Altman, Lina Wertmuller and Alan Rudolph.

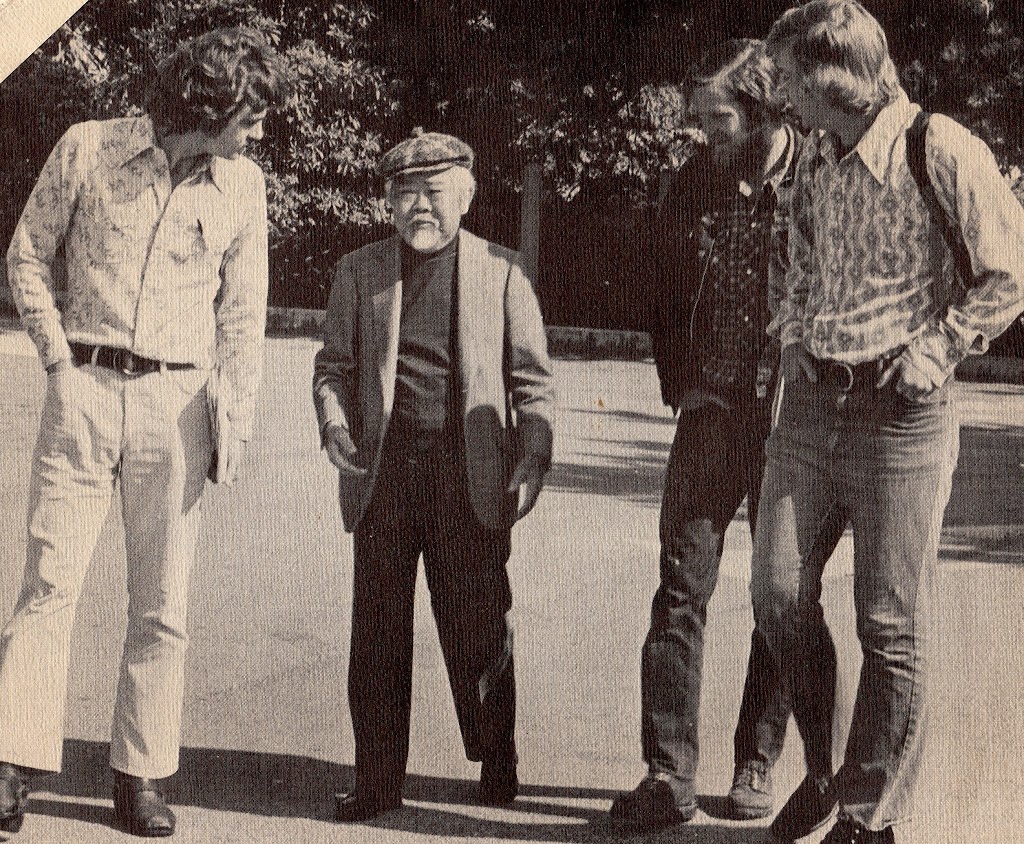

But this was also the time when many of the great directors of the past were still alive, and they also came up for a visit. I got to chat with film giants like King Vidor, Rouben Mamoulian and one of my all-time favorite directors, Frank Capra. Also the legendary cinematographer James Wong Howe. Heady times indeed! (The photo below is of three film students chatting with Mr. Howe on the campus. The one on the right with all the hair is your humble correspondent).

Film studies at that time were heavily into the “auteur theory,” which had come to us from the French critics. The theory embraced directors with a marked style that was evident in movie after movie. You can always tell a film by Welles, Hitchcock, Josef von Sternberg, Chaplin, Keaton and so on. Visual and thematic consistency are the marks of the auteur.

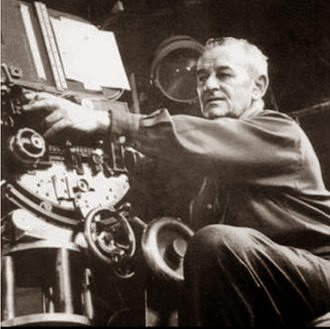

Over the years, though, I have come to appreciate more and more a director who is usually left off the list of the greats. Yet I believe he belongs near the top, and for reasons auteur theorists often reject. He belongs because he may simply be the best storyteller of them all.

William Wyler (1902 – 1981) was a studio director who refused to get tied down to one genre (usually an auteur requirement). All he did was tell one mesmerizing story after another. If you step back and look at his output, you have to shake your head in wonder. Here are just a few of his titles:

Dodsworth

Jezebel

Wuthering Heights

The Little Foxes

Mrs. Miniver

The Heiress

Classics, all. But look at what else:

A great Western, The Big Country. A great musical, Funny Girl. The greatest biblical epic, Ben-Hur.

Roman Holiday (a romance). The Desperate Hours (suspense). Friendly Persuasion(Americana).

Wyler’s films have won twice the number of Academy Awards as any other director’s. Of the 127 nominations, half of them were in the Best Picture, Director and Actor categories. No less a light than Bette Davis credited Wyler with deepening her art and turning her into a major star.

Wyler’s films have won twice the number of Academy Awards as any other director’s. Of the 127 nominations, half of them were in the Best Picture, Director and Actor categories. No less a light than Bette Davis credited Wyler with deepening her art and turning her into a major star.

And right in the middle of Wyler’s amazing career is the film I consider the greatest ever produced in America, The Best Years of Our Lives. I re-watched it recently with my family and, once again, was knocked senseless by it. The mark of a classic is that it gets better every time you see it. Best Years is such a film.

Harold Russell, Dana Andrews and Fredric March in The Best Years of Our Lives (1946)

So what was it about Wyler? He wasn’t hyperactive with his camera work (a lesson many of today’s filmmakers could benefit from). Why not? Because he didn’t want to get in the way of the story. Instead, what you’ll see in a Wyler film is a respect for the script, a superb direction of actors, and shots that are designed to tell the story, not shout out what a great director he is—even though those very virtues made him great. He was known for retake after retake, until he got just the shot and performance he wanted (many times to the consternation of his actors, who always thanked him after the film came out.)

What’s the lesson here for writers? Those who really make a dent, be it in the traditional world, indie or “blended,” are all about story.If I have to choose between a novel that has a “literary” style but a dull (and even, perhaps, a non-existent) plot, and a novel that has a killer concept and professional writing, I’ll go for the latter every time. While I can enjoy a bit of “style for style’s sake,” it can run out of steam quickly if that’s all there is. Indeed, I’ve read some highly lauded lit-fic that turned out to be, for me at least, the scribal equivalent of the emperor with no clothes.

What really rocks for me is when a great plot meets with a style that has what John D. MacDonald called “unobtrusive poetry.” That’s how I would describe William Wyler’s films. His framing is masterful. His work on Best Years with the great cinematographer Gregg Toland has never been surpassed.

Above all, tell a great story. Give us characters we can’t resist, even the bad ones. Give us “death stakes”. Give us twists, turns and cliffhangers. Give us heart.

Find your style by getting excited about your tale. That’s the key to the elusive concept of “voice.” If readers get just as excited about your story as you are, you’ve done it. You’ve clanged the bell, nabbed the brass ring, knocked a four-bagger over the green monster at Fenway.

And if you’ve never seen The Best Years of Our Lives, get it on DVD and give yourself a good three hour stretch with no interruptions. Then sit back and marvel at the genius of William Wyler, storyteller.