@jamesscottbell

I was a student in one of the best film studies programs in the country during the golden age of American movies. The 1970s saw an explosion of great independent films and directors, many of whom were picked up by major studios. Up at U.C. Santa Barbara, our intimate band of film majors got to sit around talking with exciting new directors like Martin Scorsese, Robert Altman, Lina Wertmuller and Alan Rudolph.

I was a student in one of the best film studies programs in the country during the golden age of American movies. The 1970s saw an explosion of great independent films and directors, many of whom were picked up by major studios. Up at U.C. Santa Barbara, our intimate band of film majors got to sit around talking with exciting new directors like Martin Scorsese, Robert Altman, Lina Wertmuller and Alan Rudolph.

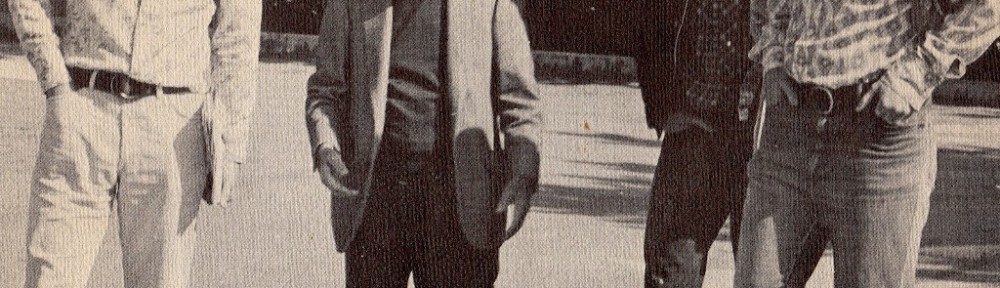

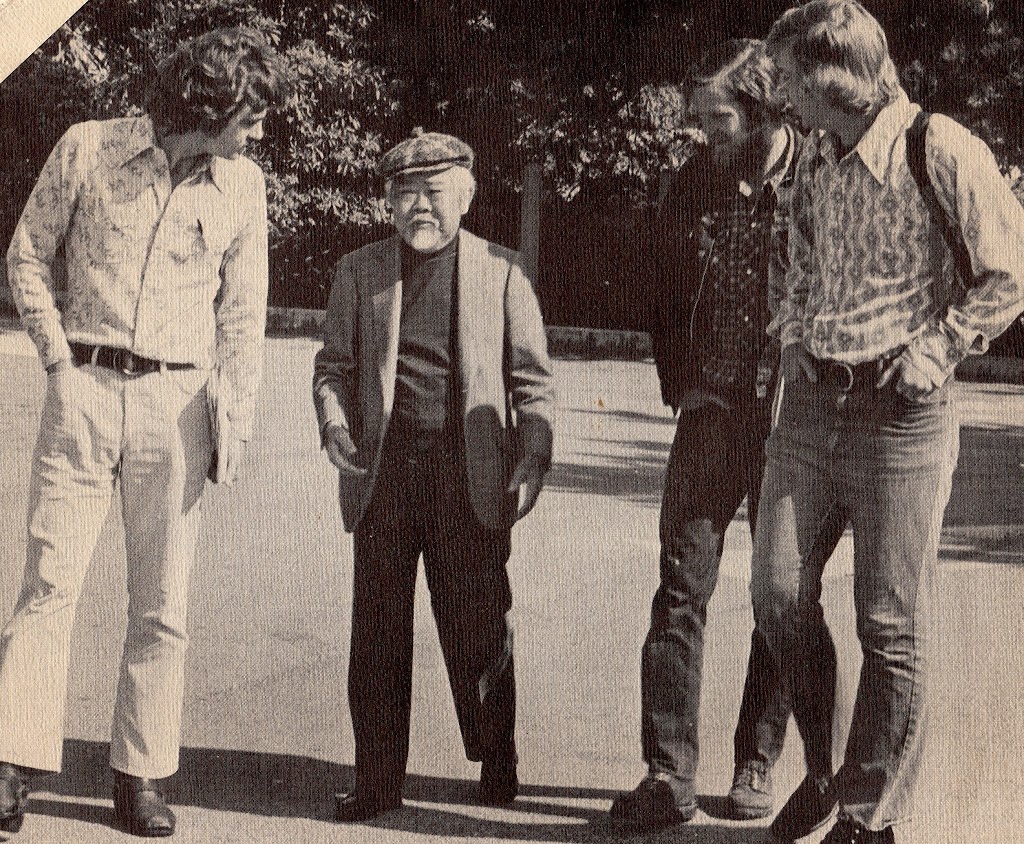

But this was also the time when many of the great directors of the past were still alive, and they also came up for a visit. I got to chat with film giants like King Vidor, Rouben Mamoulian and one of my all-time favorite directors, Frank Capra. Also the legendary cinematographer James Wong Howe. Heady times indeed! (The photo below is of three film students chatting with Mr. Howe on the campus. The one on the right with all the hair is your humble correspondent).

Film studies at that time were heavily into the “auteur theory,” which had come to us from the French critics. The theory embraced directors with a marked style that was evident in movie after movie. You can always tell a film by Welles, Hitchcock, Josef von Sternberg, Chaplin, Keaton and so on. Visual and thematic consistency are the marks of the auteur.

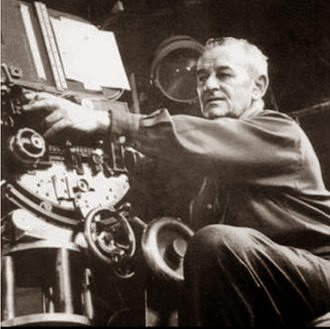

Over the years, though, I have come to appreciate more and more a director who is usually left off the list of the greats. Yet I believe he belongs near the top, and for reasons auteur theorists often reject. He belongs because he may simply be the best storyteller of them all.

William Wyler (1902 – 1981) was a studio director who refused to get tied down to one genre (usually an auteur requirement). All he did was tell one mesmerizing story after another. If you step back and look at his output, you have to shake your head in wonder. Here are just a few of his titles:

Dodsworth

Jezebel

Wuthering Heights

The Little Foxes

Mrs. Miniver

The Heiress

Classics, all. But look at what else:

A great Western, The Big Country. A great musical, Funny Girl. The greatest biblical epic, Ben-Hur.

Roman Holiday (a romance). The Desperate Hours (suspense). Friendly Persuasion(Americana).

Wyler’s films have won twice the number of Academy Awards as any other director’s. Of the 127 nominations, half of them were in the Best Picture, Director and Actor categories. No less a light than Bette Davis credited Wyler with deepening her art and turning her into a major star.

Wyler’s films have won twice the number of Academy Awards as any other director’s. Of the 127 nominations, half of them were in the Best Picture, Director and Actor categories. No less a light than Bette Davis credited Wyler with deepening her art and turning her into a major star.

And right in the middle of Wyler’s amazing career is the film I consider the greatest ever produced in America, The Best Years of Our Lives. I re-watched it recently with my family and, once again, was knocked senseless by it. The mark of a classic is that it gets better every time you see it. Best Years is such a film.

Harold Russell, Dana Andrews and Fredric March in The Best Years of Our Lives (1946)

So what was it about Wyler? He wasn’t hyperactive with his camera work (a lesson many of today’s filmmakers could benefit from). Why not? Because he didn’t want to get in the way of the story. Instead, what you’ll see in a Wyler film is a respect for the script, a superb direction of actors, and shots that are designed to tell the story, not shout out what a great director he is—even though those very virtues made him great. He was known for retake after retake, until he got just the shot and performance he wanted (many times to the consternation of his actors, who always thanked him after the film came out.)

What’s the lesson here for writers? Those who really make a dent, be it in the traditional world, indie or “blended,” are all about story.If I have to choose between a novel that has a “literary” style but a dull (and even, perhaps, a non-existent) plot, and a novel that has a killer concept and professional writing, I’ll go for the latter every time. While I can enjoy a bit of “style for style’s sake,” it can run out of steam quickly if that’s all there is. Indeed, I’ve read some highly lauded lit-fic that turned out to be, for me at least, the scribal equivalent of the emperor with no clothes.

What really rocks for me is when a great plot meets with a style that has what John D. MacDonald called “unobtrusive poetry.” That’s how I would describe William Wyler’s films. His framing is masterful. His work on Best Years with the great cinematographer Gregg Toland has never been surpassed.

Above all, tell a great story. Give us characters we can’t resist, even the bad ones. Give us “death stakes”. Give us twists, turns and cliffhangers. Give us heart.

Find your style by getting excited about your tale. That’s the key to the elusive concept of “voice.” If readers get just as excited about your story as you are, you’ve done it. You’ve clanged the bell, nabbed the brass ring, knocked a four-bagger over the green monster at Fenway.

And if you’ve never seen The Best Years of Our Lives, get it on DVD and give yourself a good three hour stretch with no interruptions. Then sit back and marvel at the genius of William Wyler, storyteller.

Just for the proverbial record, I append to your good commentary here, sir, the fact — I say fact — that literary fiction does not HAVE to present “a ‘literary’ style but a dull (and even, perhaps, a non-existent) plot.”

There is literary fiction — I say literary fiction — that bursts with story, plot, action. And I contribute this irritating footnote only because I tire — I say tire — of people running down literary fiction as if it’s a dreadful academic snore in which pale and probably anemic characters wander from one empty room to the next and muse on bad social moments of no import whatever.

It is, in most cultures, for the most part — I say the most part, not all — the literary fiction that is longest remembered, best celebrated, and most lavishly celebrated. And there is a reason for that.

None of which means that there is a single thing wrong with other genres, forms, types, and mysterious subtypes of literature not classified as “literary.” It’s all quite wonderful, especially if it’s good, as you tell us here. And you’re right — I say you’re right — that storytelling is usually the key to whatever wondrous thing makes good work a wondrous thing. Often, yes, you are right again — I say right again — that style and voice are, indeed, the manifestations of that wondrous thinginess.

But please, can you not write a fine post like this without taking a gratuitous swipe at an incorrect, unfair, and woefully tired — I say woefully tired — stereotypical myth about literary fiction?

Were you bitten by something Alec McEwan wrote last year? Did Joyce Carol Oates attack you in a dark alley? Did Joan Didion mention your mother’s army shoes? Did Dave Eggers call you up and yell at you about the shortcomings of pulp fiction?

In short, what has literary fiction done to deserve such perpetuation of groundless runnings down?

And I thank you kindly for the chance to log in my own infuriating contrariness on the matter here. 🙂

-p.

“It is, in most cultures, for the most part — I say the most part, not all — the literary fiction that is longest remembered, best celebrated, and most lavishly celebrated. And there is a reason for that.”

I think this is a matter of opinion. I am from the Chinese culture. The four most celebrated, and longest remembered novels in my culture are “The Romance of Three Kingdom”, “The Water Margin”, “Journey to the West” and “Dream of the Red Chamber”. All of them were popular fiction of their time, mostly celebrated for their amazing plot and strong characters. They didn’t set out to be literary fiction, but as time goes by, their style and usage of language become regarded as classic (mostly because people are not educated to the same standard before).

In English literature, I see Charles Dickens and Jane Austen being read and love by generations of readers, including my own daughters. They were not literary authors of their time. They did not set out to dazzle their readers with their literary brilliance, but to use language as a tool to tell their stories that pull the readers heart and soul.

I don’t think Jim’s post is trying to take a dig at literary fiction. What is literary fiction anyway? Fiction is story. Without story, without plot, without gripping character, pure brilliance of language can only go so far.

Of course most successful “literary” authors write with gripping plot and characters, and that combined with superb command of language gives reader a virtual journey like no other. However, I would argue their success is more to their stories and characterization than the language by itself.

It’s not to say language is not important. But the point is: fiction writers are storytellers. If someone sets out to write in the “literary” style without proper regard to story, then he’s going down the wrong path.

-Lam (who loves a good story, literary or otherwise)

A spirited, if perhaps misplaced defense, Porter Anderson. (And I regret it is taking us off the real purpose of my column, to bring attention to the great director William Wyler)…..but please notice how very careful I was in my assessments. A book can run out of steam IF THAT’S ALL THERE IS … I’ve read SOME lauded literary fiction that has “no clothes”….

Thus, my aim was narrow, and certainly not “a gratuitous swipe at an incorrect, unfair, and woefully tired — I say woefully tired — stereotypical myth about [all] literary fiction.” Indeed, I re-wrote that paragraph a few times to make sure it wasn’t a broad brush.

I was trying to single out one TYPE of literary fiction–that which ignores story and thinks plot is a four-letter word (ahem). I’m thinking right now of a book by a “name” that I tried to read twice. Tried to get past page thirty. It was simply self-indulgent, by which I mean the writer seemed not to care about the reader, but what the reader thought about the writer; he wanted (it seemed to me) to force the reader to by-God appreciate what a great writer he is, and you’d just better, or you will be relegated back to your cave, Neanderthal!

This is the type of fiction I had in mind, which actually gets in the way, overplays its hand. I’m not alone in this. They actually talk about it in MFA classrooms. Far from being a “tired” subject, it is perhaps the most crucial of subjects for the fiction writer: how to find that elusive balance of style and substance, form and content, sentences and story.

You bring up Joyce Carol Oates. I wrote her a fan tweet not long ago after re-reading her classic short story, “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?” Love it! I read Joan Didion with appreciation in college. Indeed, I can name several literary writers I truly enjoy and appreciate. I don’t just read Mickey Spillane, you know!

Thanks for stopping by, Porter, and spending some coffee time with us here at TKZ. Next cup’s on me.

Of course there is vibrant literary fiction and not all of it takes place in an ivory tower. Larry McMurtry grabbed me with “Texasville,” which is 1000 words of life in a small town, and didn’t let go until Dwayne laid it down in “Buffalo Ranch.” Dwayne is one of the most nuanced characters ever created and the series is highly underrated.

However, there is another hugely celebrated almost goddess-like writer taught in every college in the US that I will take a beating before I read another of her books. I dared question her in a forum one day and was roundly and soundly trounced.

Is Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath literary or genre? I can make the argument for both.

What endures for generations is a good story well told without the writer indulgently intruding in the process.

Years ago, when Stephen King proudly called himself a “hack,” I wrote a humorous post on the subject called “Confessions of a Genre Hack” and took on the great literary v. genre food fight.

In the end, only the story and how it is told matters.

You crack me up, Terri, even as you make dazzlingly good points.

Huhn… and here I thought P.A. was just being snarky.

Guess literary fiction ain’t my bag, I don’t even get it in blog comments.

Take Texasville by McMurtry (not my copy or I’ll break your hand.) It isn’t really about anything. Dwayne (a secondary character from “The Last Picture Show”) is a wildcat oil driller caught in the 1970s oil bust. Business is slow, so mostly he drives around Thalia, a Texas map dot, watching the town drowse and try to amuse itself in the blistering summer. Add in his bizarre marriage (in a later book he describes his wife as “hard to love, but easy to miss,”) and the general trainwreck his children have become. The book ends in an epic egg fight during the town festival.

Yup, that’s it.

It is engrossing character driven literary fiction that never lets up until the last egg is thrown.

In Texasville, Dwayne is frustrated and bored. In the next, he is depressed.

McMurtry is lauded for Lonesome Dove, but that book is just the tip of the iceberg of his genius.

On the way to writing an EXACTLY! YOU GO, MR. BELL! comment to this blog post, I stumbled upon my friend Porter Anderson’s comment here. I agree with what Mr. Bell is saying, Porter. It’s not so much a trashing of literary fiction, but a celebration of story in whatever genre it is found.

An interesting post, as usual., Mr. Bell. My wife and I ran into the storytelling issue last night watching something on Netflix and seems to be occurring more often. Mostly I attribute it to getting a bit cantankerous as I get older.

The story line wasn’t bad (though not original) and the acting was acceptable. The problem was that the writers or the producers had so little faith in the story that they resorted to graphic images to compensate. The other implication, the audience is dull and incapable of appreciating a properly developed story, is just depressing.

It’s not the first show that I’ve tuned out because of this problem and I don’t bother going to the movies any more.

I see it happen in novels, too, as writers confuse being graphic with being real and plot with story. In a bit of heresy, I am reevaluating the age old advice “show, don’t tell” because I am beginning to suspect that this particular pendulum has swung too far.

The constant “show, show, show” places the perceptions of the author into the story and, I think (still pondering this) blocks the natural imagination of the reader. Well-built storytelling should blend the showing into, in measured doses, the fabric of the work.

Writers like Robert Heinlein or Elmore Leonard did a lot of telling but were masters of their craft and excellent at the art of storytelling. I’m not sure that either developed plot outlines or large character sketches. They told stories.

What they excelled at was keeping the reader asking, “And then what happened?”

Paul, that is a perfect reply. Well said all the way through. Thank you for posting it.

Two words, Sidney Lumet. And a quote from Dwight Swain, “A story is never really about anything. Instead it concerns someone’s reactions to what happens.”

I love Lumet, Anon C.! See my post about Twelve Angry Men.

I love Swain, too. But your quote does not sound like him. To me at least (I could be wrong) Can you provide a source? I’d like to read the context.

Techniques of the selling writer

Chapter-3 “Plain Facts about Feelings”

First full paragraph on page 42 of the trade paperback version. Expanded quote, “In brief, although his work may on the face of it be cast rigidly in story form, it isn’t actually fiction. For a story is never really about anything. Always it concerns, instead, someone’s reactions to what happens: his feelings, his emotions, his impulses, his dreams; his ambitions; his clashing drives and inner conflicts. The external serves only to bring them into focus.”

Ah, thanks. I did need to read the context, because it makes much clearer what Swain was getting at. In the paragraph right before, he is talking about the author who thinks writing fiction is writing about “things.” The quoted paragraph emphasizes that it is most truly about how a character reacts to challenge. That’s a fair definition of plot.

And when “literary fiction” gets up caught up in that interior world, it works on the right level.

Which segues to what I believe came from Plot and Structure regarding plot driven vs. character driven. How either should use aspects of the other.

“Because he didn’t want to get in the way of the story.”

It all boils down to this, right, James? I can’t tell you how many times I have repeated this to writers who are trying to get published. Tell. Me. A. Story. Such power in those four words. From the campfire to the beside, it is magic.

I envy your contact with the great directors…so much to be learned about books from them. And for the record, “Roman Holiday” is one of my favorite movies of all time. With a pitch perfect ending that makes me blubber every time.

from campfire to BEDside,that is. 🙂

Kris, you put me in mind of the Introduction John D. MacDonald wrote for Stephen King’s first story collection, Night Shift. I just pulled it from the bookshelf. Here’s part of it:

Story. Story. Dammit, story!

Story is something happening to someone you have been led to care about. It can happen in any dimension–physical, mental, spiritual–and in combinations of those dimensions.

Without author intrustion.

Author intrusion is: “My God, Mama, look how nice I’m writing!”

I recall it was King who said something along the lines of people preferring a good story over great writing. I’ve also noticed the master of horror being referred to as a hack. Please, allow me to earn that title as I watch my tenth best-seller scream off the shelves.

I just watched “Side Effects” last weekend. I’d heard great things about it. And I was hooked from the beginning. However, I had the feeling that the director and writers lost sight as well. If you’ve seen it, maybe you can tell me why. It could be my Christian sensibilities were offended with the unnecessary sex scenes. But honestly, they detracted from what should have been a great story.

Thanks for another great post.

I happen to think Stephen King is a truly great writer, who could have been a star in literary fiction if he chose that path.

Have not seen Side Effects, so can’t comment on that.

JSB–

This is the best kind of appreciation, one that goes well beyond wide-eyed admiration in order to make a useful point. In a way, what you’ve written reflects what you have to say about William Wyler: the message, not the medium is what you’re focused on. And the message, at least for me, is this: when a writer (or filmmaker) forgets to get out of the way of his story, when his technique becomes the story, he has lost his way–and probably most of his readers.

Thanks for using Wyler to help keep us all honest.

Thanks for that, Barry. I did want that to be my takeaway. You summed it up well.

I totally agree with your take on this, Jim. I can think of a few bestselling authors who may not be technically the best writers out there, but their books are snapped up because they’re master storytellers. As a reader, I want to be entertained and enthralled by a compelling story, with great characters and a riveting plot. I advise my author clients to step back and let the characters tell the story. Don’t intrude with author asides and explanations and show-offy “aren’t I clever” prose. Let us stay immersed in the story, inside the character’s head, knowing their thoughts and feeling their emotions and reactions, worrying about them and rooting for them along the way.

“Show-offy” = obtrusive. Yes, it’s got to be organic and in service of the greater good. Right on.

Just have to add my vote to enjoying the work of William Wyler and loving The Best Years of Our Lives. In grad school, I was lucky enough to take a WWII history class taught by two Pacific theatre vets where they showed the movie and discussed it. They were impressed by the authentic portrayal of the post-war experience for returning veterans and those who welcomed them home. It gave me an entirely new level of appreciation of a film I’ve always enjoyed.

Thanks, Lynn. According to Wyler’s biography (by Jan Herman) he really fought for that authenticity, against both the studio and the Breen (“offensive content”) office. He prevailed. He also had the cast wear clothes bought from department stores, and not designed by the costume dept.

Wyler definitely made some greats. I’m going to have to look them up on Netflix and introduce them to my boys.

In the narrating side of my life I get to read a lot of books from a lot of people and see this effect of being trying to be so literary that the story gets lost. I’ve had the misfortune more than once of narrating a book that made me squeeze the bridge of my nose and wonder, “What was the publisher thinking?”

Recently I recorded a book that consisted 154K words to tell an 80K word story. The writing itself was pretty bad as well. Got lost in meaningless descriptions of everything around the characters to the point that the action was more of a relief from boredom than truly action.

On the other hand, I’ve also been privileged to narrate actual literary fiction that had such tight writing and prose and the eloquent descriptive style added to versus taking away from the writing. One such book was The Wasted Vigil by Nadeem Aslam, where the descriptives were put together such that when the reader passes a rose bush on the way to the action, the scent of the rose lingers above the stench of the burning battlefield.

One of the very few books I’ve read twice.

Picturing you narrating while squeezing your nose. I wonder if that affects the sound?

Thanks for the book recommendation.

THE BEST YEARS OF OUR LIVES is one of my favorites, too, Jim. I have the DVD and have watched it many times. It only gets better.

Mike, in the past, if it was on TV and I came to it in the middle, I’d start to watch and couldn’t stop. There’s not a dull stretch in it, which is saying something for a 3 hour drama.