by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Marx is a man who stands astride history, whose influence is so widespread and undeniable that he demands our awe and admiration, and who has made the world a better place because he was in it.

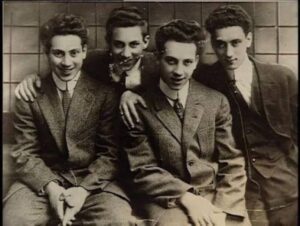

I speak, of course, of Julius Marx, better known as Groucho, born on the East Side of New York on October 2, 1890.

Create and Refine

Though a comedy icon, Julius’s initial ambition was to be a singer. At age 15 he began appearing on the vaudeville stage with an act called The Three Nightingales. He was later joined by his brothers Arthur (better known as Harpo) and Milton (Gummo). They traveled the circuit all over the land.

One night in Nagadocious, Texas, a donkey ran loose outside the theater during the act. Several audience members got up and left to see what was going on. Julius, aghast, quipped out loud, “Nagadocious is full of roaches!” He added, “The jackass is the flower of Tex-ass!”

To his surprise and delight, the audience laughed. And thus comedy entered the act.

For the next several years the boys, now joined by Leonard (Chico), developed an act built around music and a comedy sketch about a classroom. Fun in Hi Skool, like all vaudeville acts, ran under ten minutes and featured the rapid-fire dialogue and hijinx that would develop into the Marxian style. They worked it, refined it. It took over a decade before the brothers made it to Broadway with a revue called I’ll Say She Is. It was a hit, but still only a vaudeville-style show.

So the boys took the next step and developed a comedy with an actual plot—The Coconuts (1925). This was the first iteration of the Marx Brothers as we know them today. Herbert (Zeppo) had joined the troupe after Gummo dropped out.

They kept on refining and had another Broadway hit, Animal Crackers (1928), that came at the same time the movies were moving into the sound era. Perfect timing! The talkative Groucho, the language-mangling Chico, and the horn-tooting Harpo never would have made an impact in the silents.

The film version of The Coconuts came out in 1929. More refining as they learned the art of the motion picture. Two more movies followed (Animal Crackers and Monkey Business), leading finally to their greatest achievements: Horse Feathers (1932) and Duck Soup (1933).

Lesson: Never stop working, learning, correcting, refining, polishing. This is especially important in your early years. But it should also continue as long as you call yourself a writer. Never rest on your laurels (or your Hardys, either).

The Rebel

Groucho was the ultimate rebel, always sticking it to pretentions. That’s why the quintessential Groucho song is “I’m Against It” from Horse Feathers.

Margaret Dumont, a real socialite, was his favorite foil. She was upper crust and formal. Groucho romanced her, primarily for her money, while his rat-a-tat and oddly connected dialogue flummoxed her. There were other targets, too. In Duck Soup, Rufus T. Firefly (Groucho) is trying to woo Mrs. Teasdale (Dumont) in the presence of the officious Trentino (Louis Calhern):

Lesson: “The writer who is a real writer is a rebel who never stops.” – William Saroyan. “You have to evolve a permanent set of values to serve as motivation.” – Leon Uris.

Know what you believe, and be bold with it in your fiction.

Always Playing

Groucho’s comedic mind was always at play, even in “real life.” You can see it at work on his TV show You Bet Your Life, which was built upon spontaneous riffing off his guests.

This ability stayed with him as he aged. Just watch his astonishing appearance on Dick Cavett at age 81.

Even after he was slowed by a stroke, Groucho’s wit remained rapier-like. Case in point: Milton Berle was an attention grabber, always trying to take over a room. One night he showed up at a birthday party for George Burns, where the enfeebled Groucho was also a guest. After Berle loudly told a few jokes, Groucho snapped, “I don’t think you’re funny.”

“But Groucho,” Berle said, trying to save the moment. “Everything I know I stole from you.”

“Then you weren’t listening,” said Groucho.

Lesson: As writers, we should always be writing…even when we’re not writing. We must keep our minds active in looking for material. Train yourself to ask “What if?” all the time.

You’re sitting at a traffic stop. An elderly woman pushes a shopping cart of clothes in the crosswalk. You think: What if she is the missing heiress of a huge fortune? What if she is an undercover agent in disguise? What if she is an alien in a host? What if she has gold bricks hidden in that cart? You let the ideas park in your mind so the Boys in the Basement can play with them.

Also, this is good for your health. My theory on dementia is that the always-active imagination is a preventative. I point to all those great comedians who lived long and stayed sharp: George Burns, Carl Reiner, Bob Hope. And right now, Mel Brooks. By “thinking funny” every day, even in private conversation, they kept their brains active and alert. (Burns was on The Tonight Show once, aged 96, smoking his ever-present cigar. He told Johnny he smoked 15-20 cigars a day, and had a martini in the evening. “What does your doctor say about that?” Johnny asked. “My doctor’s dead,” said Burns.)

The Marketer

In 1945 the brothers were developing a spoof of the Warner Bros. classic Casablanca. Purportedly, one of the characters in the parody was to be named “Humphrey Bogus.” Wanting to protect its property, the legal team at Warner Bros. sent an inquiry about the Marx project, with the subtle threat of possible legal action.

Groucho immediately saw a way to generate publicity. He wrote a letter to Warner Bros., making more of the kerfuffle than there really was, and leaked it to the press. It became the talk of the town. Groucho was in his element, with paragraphs like these:

I just don’t understand your attitude. Even if they plan on re-releasing the picture, I am sure that the average movie fan could learn to distinguish between Ingrid Bergman and Harpo. I don’t know whether I could, but I certainly would like to try.

You claim you own “Casablanca” and that no one else can use that name without your permission. What about Warner Brothers — do you own that, too? You probably have the right to use the name Warner, but what about Brothers? Professionally, we were brothers long before you were.

Lesson: Be alert for creative marketing opportunities. For example, an event or anniversary that relates to your book might arise, giving you occasion to mention it to your email subscribers or on a blog. You can also use a deal price promotion whenever you like, as I am about to do now! (This is called the art of the segue.)

My next Mike Romeo thriller, Romeo’s Rage, is up for pre-order at the deal price of just $2.99. Yes indeed, it can be ordered now and will be auto-delivered to your Kindle on Oct. 16. Click the above link. Outside the U.S. you can go to your Amazon store and search for: B0BFRP7SQV

My next Mike Romeo thriller, Romeo’s Rage, is up for pre-order at the deal price of just $2.99. Yes indeed, it can be ordered now and will be auto-delivered to your Kindle on Oct. 16. Click the above link. Outside the U.S. you can go to your Amazon store and search for: B0BFRP7SQV

There will be a print version, too.

Well, this post has gone on long enough. And so, as Groucho once sang, “Hello, I must be going…”

Commence comments.

What’s wrong with this sentence, from an old pulp novel:

What’s wrong with this sentence, from an old pulp novel: It’s about time we talked about Casablanca. This classic consistently shows up at the top of favorite movie lists. It has perhaps the most famous ending line of all time. And of course it’s got Bogart, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, and Claude Rains—not to mention Peter Lorre and Sydney Greenstreet and a host of great Warner Bros. character actors.

It’s about time we talked about Casablanca. This classic consistently shows up at the top of favorite movie lists. It has perhaps the most famous ending line of all time. And of course it’s got Bogart, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, and Claude Rains—not to mention Peter Lorre and Sydney Greenstreet and a host of great Warner Bros. character actors.

It is my great pleasure today to do my part to bring us closer to a modicum of peace between two vexatious parties. No, not those parties. I’m talking about the Hatfields and Mc…wait, I mean the plotters and the pantsers. For I am about to offer a systematic approach to beginning a novel that has the potential to do what we all aim for—sell like dang hotcakes!

It is my great pleasure today to do my part to bring us closer to a modicum of peace between two vexatious parties. No, not those parties. I’m talking about the Hatfields and Mc…wait, I mean the plotters and the pantsers. For I am about to offer a systematic approach to beginning a novel that has the potential to do what we all aim for—sell like dang hotcakes! There’s an old joke about a guy walking into a bar with a squirrel in a cage. The bartender says, “What’s that squirrel doing here?” And the guy says, “Thinking about his next mystery.” The bartender asks what he means, and the guy says, “My squirrel is a mystery writer.”

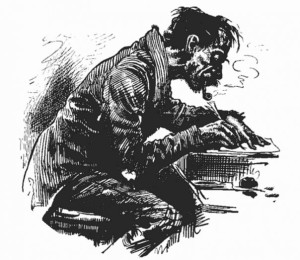

There’s an old joke about a guy walking into a bar with a squirrel in a cage. The bartender says, “What’s that squirrel doing here?” And the guy says, “Thinking about his next mystery.” The bartender asks what he means, and the guy says, “My squirrel is a mystery writer.” There’s a great Far Side cartoon (among so many great ones from the genius Gary Larson). It shows the back of a man seated at a desk. He has a pencil in his fingers, but his hands are grabbing his head in obvious frustration. In front of him are a series of discarded pages with MOBY DICK, Chapter 1 at the top. They say:

There’s a great Far Side cartoon (among so many great ones from the genius Gary Larson). It shows the back of a man seated at a desk. He has a pencil in his fingers, but his hands are grabbing his head in obvious frustration. In front of him are a series of discarded pages with MOBY DICK, Chapter 1 at the top. They say: