by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

I play three brain games each day. I start with my new addiction, Phrazle. It’s like Wordle, only with common phases. You fill in the blank boxes with words, then follow the color clues to get closer to the actual phrase. You have six chances to solve the puzzle. So far, I’ve not been knocked out. The pressure is on!

I play three brain games each day. I start with my new addiction, Phrazle. It’s like Wordle, only with common phases. You fill in the blank boxes with words, then follow the color clues to get closer to the actual phrase. You have six chances to solve the puzzle. So far, I’ve not been knocked out. The pressure is on!

Then there’s the classic, Jumble. Solve the scrambled words, then use the letters in the circles to figure out a phrase that applies to the little cartoon accompanying the puzzle. My favorites are when the answer is a play on words, indicated by quote marks. For instance, the other day, the cartoon had a man coming downstairs to the basement where his wife is working on a laptop. He’s carrying a box, and says, “Look who’s got a box of her new hit book!”

The wife says, “Wow! Working down here really paid off!”

The caption: The author converted her basement into a place to write, and the result was a—

Answer: Best “cellar.”

Chuckle.

Then there’s a crossword. Currently I’m working through a big book of ’em. Crosswords, of course, test your knowledge base. Sometimes you know the answer to a clue right off, and happily fill that in.

Other times you have—you’ll pardon the expression—no clue.

Like the other day. The clue was “1974 Peace Prize winner Eisaku.” No idea.

I did the usual, trying to fill in other rows intersecting with the answer, but was still coming up empty.

Which raises the issue of “cheating.” Is it ever okay to jump on the internet and look up the answer?

There are passionate voices on both sides. Maybe the answer depends on your purpose:

Whether or not it is considered cheating to seek out crossword puzzle help, there sure are a lot of resources to help you do just that. But perhaps there’s a difference between researching the whole answer versus receiving a prompt through a dictionary or a crossword solver. In other words, are you seeking out the answer because you want to gain more knowledge, or just because you want to solve the puzzle?

My view is that anything I can do to add to my knowledge base is fair game. [The name is Eisaku Sato, BTW. If I hadn’t looked it up, I wouldn’t know that he was Japanese prime minister from 1963 to 1972, and signed Japan onto the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. In my defense, those were my elementary through high school years, which were followed by my college days at the University of California, Santa Barbara. At UCSB, the quest for knowledge was counterpoised in equal measure by keggers, so that was kind of a wash.]

So no qualms here about looking up an answer to gain more knowledge.

Which brings me to writing, because a great part of writing pleasure for me is adding knowledge by way of research.

Here’s how I go about it.

I’m writing a scene and come to a part where I need to find something out. In my Romeo series, it is often the details of a philosophical issue. Though I’ve always loved philosophy and have read widely in it, the subject is too vast for any one mind to “know it all” (except, perhaps, for my good internet acquaintance, the public philosopher Tom V. Morris).

So I know I’ll need to study some details.

If I’m going good, I put in a placeholder: [FIL]. That means “fill in later.” I keep writing and do my study later.

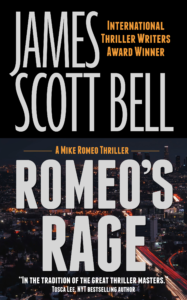

This also applies to things like police procedure or forensics. Often, I’ll I write the scene with my best guess as to how it would be handled. Some time after my writing stint, I’ll research it out or contact an expert. I did that with a scene in Romeo’s Rage where a SWAT team is called in. I wrote the scene as best I could. A day or so later I called an LAPD Captain I’d met at a community meet-and-greet. He proceeded to give me several details of SWAT procedure that I worked into the scene….and added to my knowledge base.

And just so you know, the capital of Moravia is Brno. I looked it up.

- Do you like research? When you’re writing and come to a spot that needs special knowledge, how do you proceed? Do you tend to leave your page and start down rabbit trails? Or do you keep writing, making your best guess, and save the research for later?

- What are your favorite brain games?

- Is it cheating to look something up for a crossword puzzle?

Today’s post is about a quandary faced by the writer of a series character. I’m anxious to have a robust discussion with our community of sharp readers and writers about it. Simply put, the problem is love.

Today’s post is about a quandary faced by the writer of a series character. I’m anxious to have a robust discussion with our community of sharp readers and writers about it. Simply put, the problem is love.

What was a time when a seemingly random event or conversation changed your life, or way of thinking, in a significant way?

What was a time when a seemingly random event or conversation changed your life, or way of thinking, in a significant way? But there’s one name that deserves to be mentioned here, for he was a quadruple threat: he could sing, dance, and act equally well in comedy or drama. His star flew across stage, screen, TV, and Vegas.

But there’s one name that deserves to be mentioned here, for he was a quadruple threat: he could sing, dance, and act equally well in comedy or drama. His star flew across stage, screen, TV, and Vegas. “Success is not the result of spontaneous combustion. You must set yourself on fire.” – Reggie Leach, retired Canadian hockey player.

“Success is not the result of spontaneous combustion. You must set yourself on fire.” – Reggie Leach, retired Canadian hockey player. James N. Frey, author of the popular craft books

James N. Frey, author of the popular craft books