by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Snidely Whiplash

We all know the first rule (wink) about villains is to not make them like Snidely Whiplash. Those of you too young to understand this reference are culturally bereft, so I’m here to help. Snidely was the name of the foil for Dudley Do-Right of the Mounties, a cartoon character who first appeared on the Rocky and Bullwinkle Show, which was the creation of the great Jay Ward staff of writers. Both Dudley and Snidely were caricatures from the days of silent movie serials, where the mustache-twirling bad guy tied the girl to the railroad tracks and other nasty things.

Pure evil villains are, therefore, stereotypical and boring. We need to give them a backstory, a justification (they think they are in the right), and even a little sympathy.

What I want to consider today is charm. For me, the most memorable villains are those whose personalities attract rather than repel. For as the Bible notes, Satan may appear as “an angel of light.”

My top two villains in this regard are:

- Iago

We’ve all heard of Shakespeare’s Iago, and perhaps picture him as a conniving, nasty reprobate. But that’s not how the characters in the play see him. Othello himself calls him “honest, honest Iago.” Cassio trusts him implicitly, would like to be like him. Harold Bloom brings out the obvious comparison to Satan in Milton’s Paradise Lost, the latter undoubtedly inspired by the former.

I always wanted to play Iago. Earle Hyman, a great Othello, told me I’d be perfect because of my open, honest face (ha! I became a lawyer instead). Iago drives the play. He has eight soliloquies (Othello has but three) and they are valid insights into human nature, twisted to suit Iago’s purposes. In one famous speech he tells the love-struck Roderigo to get over it through the power of his will:

Virtue? A fig! ’Tis in ourselves that we are thus or thus. Our bodies are our gardens, to the which our wills are gardeners. So that if we will plant nettles or sow lettuce, set hyssop and weed up thyme, supply it with one gender of herbs or distract it with many, either to have it sterile with idleness or manured with industry, why the power and corrigible authority of this lies in our wills. If the balance of our lives had not one scale of reason to poise another of sensuality, the blood and baseness of our natures would conduct us to most prepost’rous conclusions. But we have reason to cool our raging motions, our carnal stings, our unbitted lusts—whereof I take this that you call love to be a sect, or scion.

He goes on to tell Roderigo that what he calls love “is merely a lust of the blood and a permission of the will.” Iago then appeals to his manhood: “Come, be a man!” and “Put money in thy purse.” When Roderigo toddles off to do as Iago suggests, Iago faces the audience and says he has “made my fool my purse.”

Great villains have the charm to turn people into fools.

- Harry Lime

Lime is the villain in Carol Reed’s classic The Third Man (1949). Played by Orson Welles, Lime dominates the film even though, for the first hour, he’s not even seen! When he first appears, one can see immediately why the beautiful Anna (Valli) loves him and why his best friend Holly (Joseph Cotten) wants so badly to find him. His magnetism radiates off the screen. Watch his duly famous intro:

Holly learns that Harry is running a black market business in diluted penicillin. At first he refuses to believe it, but Major Calloway (Trevor Howard) shows him the undeniable evidence at the children’s hospital. One of the dark consequences of Lime’s penicillin are the horrible outcomes to children who got dosed for meningitis. As Calloway says, “The lucky ones died.”

So here you have the most heinous of crimes, done by the most charming of evil doers. What does that do to us? The emotional cross-currents take us more deeply into the story than we can experience any other way.

Thus, I have advised writers to give their villains a closing argument, as if standing in front of a jury. Lime actually has one and delivers it to Holly. They are in a car on a Ferris wheel and, looking down at the ant-like people, Lime asks:

Would you really feel any pity if one of those dots stopped moving forever? If I offered you 20,000 pounds for every dot that stopped, would you really, old man, tell me to keep my money? Or would you calculate how many dots you could afford to spend? Free of income tax, old man, free of income tax.

As they are about to part, Lime gives him the conclusion to his closing argument:

Who isn’t charmed by that? The audience certainly was, and the fan letters came pouring in…for Welles! So much so that they created a radio show called The Adventures of Harry Lime. It was a prequel to the movie, with Welles reprising his role and playing it more as a lovable rogue than an evil black marketeer.

Thus, the charming villain is the most dangerous villain of all.

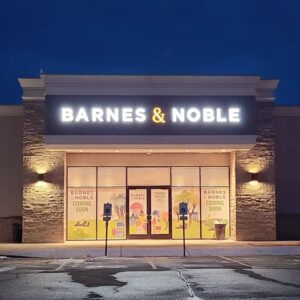

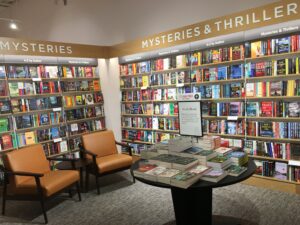

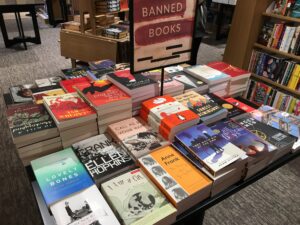

The arrangement is an attractive, intriguing labyrinth. Walls of books divide the space into discrete sections: fiction, new releases, mystery-thriller, sweet or spicy romance, westerns, nonfiction, history, religion, self-help, children’s and YA, Manga, graphic novels, and more.

The arrangement is an attractive, intriguing labyrinth. Walls of books divide the space into discrete sections: fiction, new releases, mystery-thriller, sweet or spicy romance, westerns, nonfiction, history, religion, self-help, children’s and YA, Manga, graphic novels, and more.

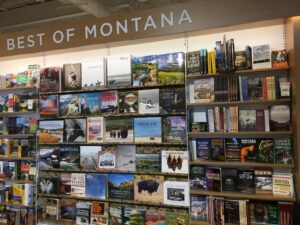

One large wall displays books about Montana, from hiking guides to history to Glacier National Park to bison, wolves, and grizzlies to mining and logging to pioneer memoirs.

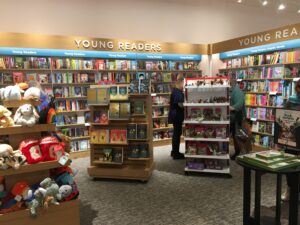

One large wall displays books about Montana, from hiking guides to history to Glacier National Park to bison, wolves, and grizzlies to mining and logging to pioneer memoirs. Especially encouraging are expansive sections devoted to young readers, covering the range from picture books to YA novels.

Especially encouraging are expansive sections devoted to young readers, covering the range from picture books to YA novels.

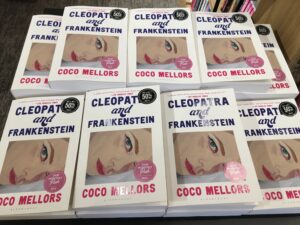

The signing table was set up just inside the front entrance. Daniel had stacks of my books ready, along with stickers that read “Signed Edition.” I waved at him across the store, but he barely had time to nod because he was so busy ringing up sales with two other cashiers.

The signing table was set up just inside the front entrance. Daniel had stacks of my books ready, along with stickers that read “Signed Edition.” I waved at him across the store, but he barely had time to nod because he was so busy ringing up sales with two other cashiers. That’s how Daniel was able to order and stock

That’s how Daniel was able to order and stock

Private pilot Cassie Deakin is in for a string of surprises when she lands in the middle of a murder mystery. Even Fiddlesticks the cat takes on a new persona that’s shocking.

Private pilot Cassie Deakin is in for a string of surprises when she lands in the middle of a murder mystery. Even Fiddlesticks the cat takes on a new persona that’s shocking. “Build a better mousetrap, and the world will beat a path to your door.” That old chestnut is usually attributed to Emerson, who actually put it this way:

“Build a better mousetrap, and the world will beat a path to your door.” That old chestnut is usually attributed to Emerson, who actually put it this way: