In the spirit of today’s Words of Wisdom, we’re cutting to the chase to talk about thrillers: defining them, the qualities of a thriller hero, and a few truly classic examples. The full posts for each excerpt are well-worth reading, and are linked via the listed dates.

First, let’s define a thriller and how it differs from a mystery?

Although thrillers are usually considered a sub-genre of mysteries, I believe there are some interesting differences. I look at a thriller as being a mystery in reverse. By that I mean that the typical murder mystery usually starts with the discovery of a crime. The rest of the book is an attempt to figure out who committed the crime.

I see a thriller as being just the opposite; the book often begins with a threat of some kind, and the rest of the story is trying to figure out how to prevent it from happening. And unlike the typical mystery where the antagonist may not be known until the end, with a thriller we pretty much know who the bad guy is right from the get-go.

So with that basic distinction in mind, let’s list a few of the most common elements found in thrillers.

- The Ticking Clock. Without the ticking clock such as the doomsday deadline, suspense would be hard if not impossible to create. Even with a thriller like HUNT FOR RED OCTOBER which dealt with slow-moving submarines, Tom Clancy built in the ticking clock of the Soviets trying to find and destroy the Red October before it could make it to the safety of U.S. waters. He masterfully created tension and suspense with an ever-looming ticking clock.

- High Concept. In Hollywood, the term high concept is the ability to describe a script in one or two sentences usually by comparing it to two previously known motion pictures. For instance, let’s say I’ve got a great idea for a movie. It’s a wacky, zany look at the lighter side of Middle Earth, sort of a ONE FLEW OVER THE CUCKOO’S NEST meets LORD OF THE RINGS. If you’ve seen both of those movies, you’ll get an immediate visual idea of what my movie is about. High concept Hollywood style.

But with thrillers, high concept is a bit different. A book with a high concept theme is one that contains a radical or somewhat outlandish premise. For example, what if Jesus actually married, had children, and his bloodline survived down to present day? And what if the Church knew it and kept it a secret? You can’t get more outlandish than the high concept of THE DA VINCI CODE.

What if a great white shark took on a maniacal persona and seemed to systematically terrorized a small New England resort island? That’s the outlandish concept of Benchley’s thriller JAWS.

What if someone managed to clone dinosaurs from the DNA found in fossilized mosquitoes and built a theme park that went terribly wrong? You get the idea.

- High Stakes. Unlike the typical murder mystery, the stakes in a thriller are usually very high. Using Dan Brown’s example again, if the premise were proven to be true, it would undermine the very foundation of Christianity and shake the belief system of over a billion faithful. Those are high stakes by anyone’s standards.

- Larger-Than-Life Characters. In most mysteries, the protagonist may play a huge role in the story, but that doesn’t make them larger than life. By contrast, Dirk Pitt, Jason Bourne, Jack Ryan, Jack Bauer, James Bond, Laura Craft, Indiana Jones, Dr. Hannibal Lecter, and one that’s closest to my heart, Cotten Stone, are all larger-than-life characters in their respective worlds.

Joe Moore—June 29, 2011

I’ve come up with this list of desired qualities for the hero or heroine of a page-turning suspenseful mystery, romantic suspense, or thriller novel.

Heroes and heroines of bestselling thrillers need most of these attributes:

~ Clever. They need to be smart enough to figure out the clues and outsmart the villain. Readers don’t want to feel they’re smarter than the lead character. They don’t want to say, “Oh, come on! Figure it out!”

~ Resourceful. Think MacGyver, Katniss of The Hunger Games, Harry Potter, Indiana Jones, Jason Bourne, or Dr. Richard Kimble of The Fugitive. The hero needs to be able to use ingenuity and whatever’s at his disposal to get out of any jams he finds himself in and also to find and defeat the bad guy(s).

~ Experienced. They’ve done things and been places. They’ve had a variety of tough life experiences that have helped them grow. They’ve “lived” and are stronger and more resilient for it. They’re definitely not naïve.

~ Determined. Your hero or heroine needs to be tenacious and resilient. They keep going. They don’t cave under pressure or adversity. They have a goal and stick to it, despite personal discomforts like fatigue, hunger, injuries, and threats.

~ Courageous. Bravery is essential, as readers want to look up to him/her. Any heroes who are tentative or fearful early on should soon find courage they didn’t know they had. The challenges and dangers they face force them to be stronger, creating growth and an interesting character arc for them.

~ Physically fit. Your heroine or hero needs to be up to the physical challenges facing her/him. It’s more believable if they jog or work out regularly, like Joe Pike running uphill carrying a 40-pound backpack. Don’t lose reader credibility by making your character perform feats you haven’t built into their makeup, abilities you can’t justify by what we know about them so far.

~ Skilled. To defeat those clever, skilled villains, they almost always have some special skills and talents to draw on when the going gets rough. For example, Katniss in Hunger Games is a master archer and knows how to track and survive in the woods, Jack Reacher has his army police training and size to draw on, and Joe Pike has multiple talents, including stealth.

~ Charismatic. Attractive in some way. Fascinating, appealing, and enigmatic. Maybe even sexy. People are drawn to him or her.

~ Confident but not overly cocky. Stay away from arrogant, unless you’re going for less-than-realistic caricatures like James Bond.

~ Passionate, but not overly emotional. Often calm under fire, steadfast. Usually don’t break under pressure. Often intense about what they feel is right and wrong, but “the strong, silent type” is common among current popular thrillers – “a man of few words,” like Joe Pike or Jack Reacher or Harry Bosch.

~ Unique, unpredictable. They have a special world view, and a distinctive background and attitude that sets them apart from others. They’ll often act in surprising ways, which keeps their adversaries off-balance and the readers on edge.

~ Complex. Imperfect, with some inner conflict. Guard against having a perfect or invincible hero or heroine. Make them human, with some self-doubt and fear, so readers worry more about the nasty villains defeating them and get more emotionally invested in their story.

Jodie Renner—February 6, 2013

Last month I read Anna Karenina for the first time. Truth to tell, I had mixed feelings about the novel. Many chapters were glacially slow. The descriptions of Russian rural politics couldn’t have been more boring. Worse, none of the main characters — Anna, Vronsky, Levin — was particularly likeable. Still, I got caught up in the soap-opera plot, the whole nineteenth-century aristocratic mating dance. And the book’s climax blew away. Every thriller writer can learn something from seeing how Leo Tolstoy handled Anna’s suicide.

It’s not really a spoiler to reveal that Anna kills herself, is it? It’s like the crucifixion in the New Testament — everyone knows it’s coming. In fact, the only thing that kept me going through the boring chapters was the anticipation of seeing Anna throw herself under that train. And Tolstoy didn’t disappoint me. The chapter showing Anna’s nervous breakdown in the hours before her suicide is brilliant. I loved her nihilistic, stream-of-consciousness observations as she rides in her carriage through the Moscow streets: “There is nothing funny, nothing amusing, really. Everything’s hateful. They are ringing the bell for vespers — how carefully that shopkeeper crosses himself, as if he were afraid of dropping something! Why these churches, the bells and the humbug? Just to hide the fact that we all hate each other.”

And then the fatal act itself, six pages later, described so pitilessly: “Exactly at the moment when the space between the wheels drew level with her she threw aside her red bag and drawing her head down between her shoulders dropped on her hands under the train car, and with a light movement, as though she would rise again at once, sank on to her knees. At that same instant she became horror-struck at what she was doing. ‘Where am I? What am I doing? Why?’ She tried to get up, to throw herself back; but something huge and relentless struck her on the head and dragged her down on her back.”

After finishing the book I tried to think of other classic novels that offer useful lessons for thriller writers. Here are four more canonical works that made a big impression on me:

Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens. Mr. Ringel, my sixth-grade teacher, read this book out loud to our class over a period of several weeks. Reading a Dickens novel to a class of unruly eleven-year-olds was a pretty ballsy thing to do. I remember several occasions when Mr. Ringel had to yell at the miscreants in the back of the classroom who were whispering insults at one another instead of listening to his narration. But no one whispered when he read the scene in which Charles Darnay and his family make their perilous escape from Paris. It’s the great-granddaddy of chase scenes, and thriller writers have been unashamedly imitating it for the past 150 years: “O pity us, kind Heaven, and help us! Look out, look out, and see if we are pursued! The wind is rushing after us, and the clouds are flying after us, and the moon is plunging after us, and the whole wild night is in pursuit of us; but, so far, we are pursued by nothing else.”

Les Miserables by Victor Hugo. This novel is long. It has a whole miscellany of odd things that got left on the cutting-room floor when the book was turned into a Broadway musical. There are learned disquisitions on medieval monastic orders, the sewers beneath Paris, and the nature of quicksand. And though I wasn’t terribly interested in these subjects, I didn’t mind wading through those chapters. I was so desperate to find out what was going to happen to Jean Valjean, there was no way I could stop reading. Hugo was a master of the cliffhanger.

Mark Alpert—February 22, 2014

***

- Which elements of a thriller are essential, to you?

- What other qualities of character are necessary for a thriller hero?

- What is a classic novel you feel has thriller-like qualities?

Design

Design

There are many ways to write a novel. That much has been made quite clear on TKZ and in the comments thereto.

There are many ways to write a novel. That much has been made quite clear on TKZ and in the comments thereto.

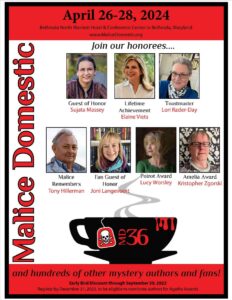

The Malice Domestic mystery conference is honoring me with the Lifetime Achievement Award for Malice 36 April 26-28, 2024. Malice Domestic is an annual fan convention in Bethesda, Maryland. I’m thrilled to be part of a star-studded line-up next year.

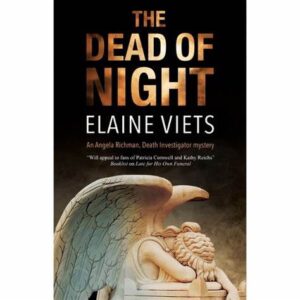

The Malice Domestic mystery conference is honoring me with the Lifetime Achievement Award for Malice 36 April 26-28, 2024. Malice Domestic is an annual fan convention in Bethesda, Maryland. I’m thrilled to be part of a star-studded line-up next year. The Dead of Night, my new Angela Richman, death investigator mystery, is available in book stores and online:

The Dead of Night, my new Angela Richman, death investigator mystery, is available in book stores and online: