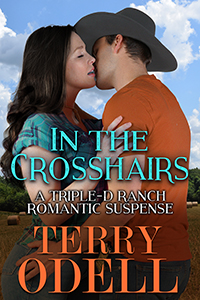

This week I finished the first draft of my work in progress, Texas Gravel, when I typed The End. This is number fourteen, and I had the same feeling of satisfaction as when I completed my first novel over ten years ago. It took years to finish that one and have it ready for publication, but this one unfolded in a matter of months.

Now the real fun begins.

Writing is enjoyable, or I wouldn’t do it. World-building is fun and rewarding. There’s great satisfaction in creating and developing characters, exploring whatever it is that makes them tick, and bestowing upon them all the ingredients necessary to become real in our imaginations.

But my absolute favorite part of the process is editing. Some folks approach it with dread, and others simply endure it as just another part of the process. I look forward to starting with the first sentence and combing through several months’ worth of creativity for a variety of issues.

There are as many theories about how to edit as there are editors and authors. Some say “write in one room, edit in another.”

Well, I guess that’s a good idea, but for me, that’s impossible. I write wherever I light on any particular morning. It might be at my desk, surrounded by bookshelves that reach sixteen feet high. Other days it might be feet up in my recliner, propped up on the couch, on perched on a stool at the kitchen island. More recently, I wrote much of the second act on the kitchen island in our weekend place, while workers made enough racket to wake the dead.

One of my favorite places to work is lying on our bed with my laptop across my legs ala Mark Twain. There’s a great photo of him partially under the covers with a typewriter on his lap and if memory serves, he’s the first novelist to write a book on the Iron Maiden.

I edit the same way, and in those same locations, and then some. It might drive some folks nuts, but I’ll work on the laptop for a while, then move to the Mac in my office and perch there for a day or two, reminiscent when I had a real job in an office.

My first edits are part of the first draft. I’ve told you how each morning I read what came the day before, edit those pages, and then slide into the current day’s work. In essence, I edit every day as I go.

Then once finished, I dig into the first draft, rewriting and tightening sentences, and looking for errors in continuity. I have a bad habit of forgetting what kind of cars my characters drive, or any number of descriptions about what they do, like, or feel. This is also when I start to notice repetitive words and do a search. The first time it happened in The Rock Hole, I realized I’d used the word “porch” two hundred and twenty-seven times.

That’s 227.

It happens all the time. A host of other words including, windows, car, sedan, door (especially door), and a host of others make wayyyy too many appearances in my work. I won’t even search for the word, “that.” This gives me the opportunity to look for useless words such as “just” or “very” or those pesky adverbs I’ve discussed in the past. Editing on the screen gives me the chance to rewrite even more sentences and tighten them up. I even more entire paragraphs around, or pull a sentence from here and there, and plug them into different places to make the draft read better.

I’m pretty good at setting scenes, but this is when I add a lot more description and detail to locations, people, and their actions to put the reader in that place and time. At this point the manuscript grows, even though sentences and paragraphs melt away with alarming frequency.

By the original draft’s third act, I’m thinking and typing fast, pushing hard to get the framework concreted into place. Detail takes a back seat to the action at that point, and editing is the time to expand certain scenes that were cheated the first time. I look for the opportunity to use all of our senses, sight, sound, smell, touch, and even taste. Many writers forget those descriptors and their work would likely improve if they added details to make it even more realistic.

This is where “He smelled woodsmoke” becomes “Smoke from a distant fire reminded him autumn was the time to burn leaves,” or “Burning leaves created a fog-like haze in the chilly autumn air.” The edits and possibilities are endless.

Here is where we can lift our vocabularies. We tend to use the same common words over and over, but now is the time to add excitement and richness with the use of the right word. Dialogue changes at this point, adding and subtracting, and getting into the character’s rhythm of speaking and acting.

Editing on the screen is fine, but I need to see it in true print form, as close to a real book as possible. It’s now the time to print the manuscript and read it again from start to finish. It’s stunning to see how many typos I’ve already missed, or sentences or paragraphs that are in the wrong place. Despite all the work I did in the first draft and the electronic edits, the printed manuscript is a riot of scratched out words, replaced words, corrected sentences, and margins full of hand-written notes and questions.

Finished, the pages then go to my personal editor, The Bride, who has a degree in journalism and worked several years as a newspaper reporter before she came back from the dark side. Her copy is marked with even more typos that I missed, and suggestions in the margins, and questions about a character’s actions or what they might or might not do in a particular situation.

Back at my desk with two different hard copies, I type in all those changes and the completed manuscript is polished and ready for my agent.

Maybe this peek behind the curtain in my writing world will help novice writers realize there’s no magical right or wrong way to edit. It’s about writing and rewriting as they attempt to complete that polished manuscript and find their place in the publishing world.

Do what works for you.

Are the creative juices flowing on this fine Friday? Great! Tell us…

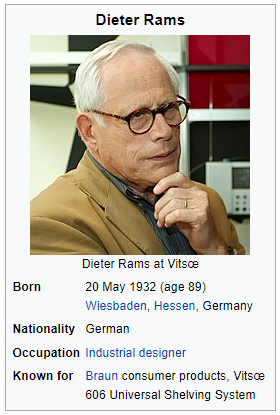

Are the creative juices flowing on this fine Friday? Great! Tell us… Dieter Rams is German and, true to being German, is quality-orientated and detail-driven. Rams, now 89, was schooled in architecture but transformed into one of the world’s leading consumer product designers. His ingenuity and vision were instrumental in thousands of items sold by giants like Braun, Gillette, and European furniture maker Vitsoe.

Dieter Rams is German and, true to being German, is quality-orientated and detail-driven. Rams, now 89, was schooled in architecture but transformed into one of the world’s leading consumer product designers. His ingenuity and vision were instrumental in thousands of items sold by giants like Braun, Gillette, and European furniture maker Vitsoe. Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective with a second career investigating deaths as a coroner. Now, he’s a crime writer and indie publisher with some twenty works in the public arena.

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective with a second career investigating deaths as a coroner. Now, he’s a crime writer and indie publisher with some twenty works in the public arena.

It may be the most famous (infamous?) case of writer’s block in the annals of American lit: George R. R. Martin is having trouble completing his epic fantasy series A Song of Ice and Fire (of which A Game of Thrones is the first volume). It’s been over ten years since the last book, A Dance with Dragons, came out, and there is no pub date in sight for the next one, titled The Winds of Winter.

It may be the most famous (infamous?) case of writer’s block in the annals of American lit: George R. R. Martin is having trouble completing his epic fantasy series A Song of Ice and Fire (of which A Game of Thrones is the first volume). It’s been over ten years since the last book, A Dance with Dragons, came out, and there is no pub date in sight for the next one, titled The Winds of Winter.