What was a time when a seemingly random event or conversation changed your life, or way of thinking, in a significant way?

What was a time when a seemingly random event or conversation changed your life, or way of thinking, in a significant way?

Rejection Slips

By Elaine Viets

Feeling discouraged, writers? Tired of papering your walls with rejection slips?

When I feel down, I turn to the good book. Not THE good book, but a good book by Elaine Borish called “Unpublishable! Rejected writers from Jane Austen to Zane Grey.”

If you’ve been rebuffed by a publisher, you’re in good company. So was Agatha Christie. Borish says it took Dame Agatha four years to find a publisher for her first novel, “The Mysterious Affair at Styles” – and then it sat on a desk for another eighteen months. The publisher suggested some changes to the ending, and Agatha made them. Belgian detective Hercule Poirot finally made his debut in 1920.

Agatha Christie wrote more than ninety titles, and “The Mysterious Affair at Styles” is still in print.

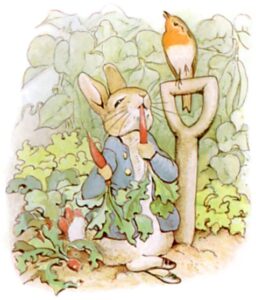

Beatrix Potter, the creator of Peter Rabbit and Flopsy, Mopsy and Cottontail, was a hybrid author. Her “Peter Rabbit” was rejected by six publishers. She used black-and-white sketches, since she was worried that color pictures would make the book too expensive for children. Beatrix finally self-published “Peter Rabbit.” It went through two printings.

In 1901, Beatrix submitted Peter Rabbit again, and the traditional publisher politely rejected it: “As it is too late to produce a book for this season, we think it best to decline your kind offer at any rate for this year.”

The next time Beatrix submitted the book, she had color illustrations. The first edition sold out before the 1902 publication. By 1903, sales were multiplying like, well . . . rabbits. She’d sold 50,000 copies, and lived hoppily ever after.

Dorothy L. Sayers’ books were definitely not for children. “Whose Body?,” the first mystery by the rebellious Oxford scholar, was rejected by several UK publishers for “coarseness” in 1920. Today, the risque parts wouldn’t raise an eyebrow. The novel opened this way:

“Oh, damn!” said Lord Peter Wimsey.

Besides that four-letter word, Dorothy L.’s first book is about the disappearance of a Jewish financier, Sir Reuben Levy. Borish tells us, “When a naked corpse turns up in a bath, Inspector Sugg is eager to identify him as Levy.” Lord Peter says it can’t be “by the evidence of my own eyes.”

And the evidence? The body was (gasp) uncircumcised.

Dorothy L., desperate for money, revised her story, making sure the body could not be mistaken for a rich man. The deceased had “callused hands, blistered feet, decayed teeth” and more. An American publisher bought “Whose Body?” It was published in New York in 1923, and Dorothy was on the way to fame and fortune. Borish writes, rather gleefully, “consider the last words spoken by Lord Peter in the last novel: ‘Oh damn!’”

George Orwell had his masterpiece, “Animal Farm,” turned down by no less than T. S. Eliot, a big deal at UK publishers Faber and Faber. Like many in the upper echelons of publishing, Eliot missed the point when he rejected Orwell: “Your pigs are far more intelligent than the other animals, and therefore the best qualified to run the farm . . . What was needed (someone might argue) was not more communism but more public-spirited pigs.”

George Orwell had his masterpiece, “Animal Farm,” turned down by no less than T. S. Eliot, a big deal at UK publishers Faber and Faber. Like many in the upper echelons of publishing, Eliot missed the point when he rejected Orwell: “Your pigs are far more intelligent than the other animals, and therefore the best qualified to run the farm . . . What was needed (someone might argue) was not more communism but more public-spirited pigs.”

Another publisher, Fredric Warburg, took the book and paid Orwell a hundred pounds. Orwell had the last laugh – Borish says the book sold 25,000 hardcovers in the first five years.

Anthony “A Clockwork Orange” Burgess had a novel about his grammar school experience – “The Worm and the Ring” – rejected because it was “too Catholic and too guilt-ridden.”

Publishers outdid themselves with boneheaded reasons to reject bestsellers. Conan Doyle’s first Sherlock Holmes novel, “A Study in Scarlet,” was turned down by the prestigious Cornhill magazine because it was too much like the other “shilling shockers” already on the market. The editor said it was too long “and would require an entire issue” – but it was “too short for a single story.” Another publisher sent the manuscript back unread. A third bought the rights for a measly twenty-five pounds, and let it sit around for year. It was published in 1887, and then brought out as a book, but Conan Doyle didn’t get any money from that because he’d sold the rights. Worse, the book was pirated in the U.S. Doyle wrote a couple of historical fiction works. Then an American editor, looking for UK talent, had dinner with Doyle and Oscar Wilde and signed them both up. Wilde wrote “The Picture of Dorian Gray” and Doyle did “The Sign of the Four.”

Publishers outdid themselves with boneheaded reasons to reject bestsellers. Conan Doyle’s first Sherlock Holmes novel, “A Study in Scarlet,” was turned down by the prestigious Cornhill magazine because it was too much like the other “shilling shockers” already on the market. The editor said it was too long “and would require an entire issue” – but it was “too short for a single story.” Another publisher sent the manuscript back unread. A third bought the rights for a measly twenty-five pounds, and let it sit around for year. It was published in 1887, and then brought out as a book, but Conan Doyle didn’t get any money from that because he’d sold the rights. Worse, the book was pirated in the U.S. Doyle wrote a couple of historical fiction works. Then an American editor, looking for UK talent, had dinner with Doyle and Oscar Wilde and signed them both up. Wilde wrote “The Picture of Dorian Gray” and Doyle did “The Sign of the Four.”

These writers endured humiliation, insults, swindles – and in many cases, poverty – and still went on to write books that are read today.

Orwell talked about an embittered Russian who said, “Writing is bosh. There is only one way to make money at writing, and that is to marry the publisher’s daughter.”

Obviously, we writers have to pay attention to rejections sometimes. My agent gave me a good rule of thumb: “If you get the same reason for rejection repeatedly – your plot isn’t twisty enough, or you have too many secondary characters – it’s time to pay attention.”

How many times have you ignored rejections?

Kings River Life says “Late for His Own Funeral” is “a fascinating exploration of sex workers, high society, and the ways in which they feed off of one another.” Buy my new Angela Richman, Death Investigator mystery here. https://tinyurl.com/4dn2ydfd

Kings River Life says “Late for His Own Funeral” is “a fascinating exploration of sex workers, high society, and the ways in which they feed off of one another.” Buy my new Angela Richman, Death Investigator mystery here. https://tinyurl.com/4dn2ydfd

Give Yourself Permission

Give Yourself Permission

Terry Odell

There have been several posts recently about how to motivate yourself to write, how to increase productivity, how to “do the job.” I’d like to take a moment to look at the other side of the picture.

There have been several posts recently about how to motivate yourself to write, how to increase productivity, how to “do the job.” I’d like to take a moment to look at the other side of the picture.

(Disclaimer: I’m an indie author and am not on deadline at the moment.)

Recent events—both positive and negative—have pulled me away from the current manuscript. I had a short visit with my mother, followed by a planned week’s vacation which was an organized tour, and we were on the go all the time. When I returned home, ready to tackle the WIP, my mother’s failing health had taken a rapid downturn, and I dropped everything to return to LA. My brother and I spent two weeks dealing with the funeral and trying to get her house cleared out enough to put on the market. She’d lived in the house since 1958 and apparently threw nothing away.

At any rate, all the sorting and wrapping, bagging, and packing was both physically and mentally exhausting. Although I’d intended to use “down time” to work on the manuscript (even brought my regular keyboard), there wasn’t any.

I did have one pleasant break—I met with JSB for lunch one day, and it was nice to talk about writing, and a glimmer of a spark to get back to the book flashed for a moment or two.

At first, I told myself that I had reached a “need to do some research” stopping point before I left, but I faced reality. Even with that information I wasn’t going to be able to write. Constant interruptions, distractions, and the pressure to get everything done wasn’t conducive to productivity—at least productivity that wouldn’t end up being the victim of the delete key.

I gave myself permission to set the manuscript aside and not feel guilty about it. The same went for a presence on social media. I checked emails, but set most of them aside to deal with when I got home.

While writing every day is part of the “job”, there are legitimate reasons for taking a leave of absence. When life intervenes and you have to step away, accept it. The manuscript will still be there.

Now that I’m home in my familiar writing environment, I’ll be catching up with all the “life” stuff that accumulates while you’re away, but also with easing back into the writing. I wrote a post some time ago about getting back in the writing groove, but I thought it was appropriate to repeat my tips here:

Get rid of chores that will nag.

If you are going to worry about cleaning house, paying bills, going through email, take the time to get the critical things dealt with. Otherwise you’re not going to be focused on your writing. If you’re a ‘write first’ person, don’t open anything other than your word processing program.

Do critiques for my crit group.

This might seem counterproductive, but freeing your brain from your own plot issues and looking at someone else’s writing can help get your brain into thinking about the craft itself.

Work on other ‘writing’ chores.

For me, it can be blog posts, or forum participation. Just take it easy on social media time.

Deal with critique group feedback.

Normally, I’m many chapters ahead of my subs to my crit group. If I start with their feedback on earlier chapters, I get back into the story, but more critically than if I simply read the chapters. And they might point out plot holes that need to be dealt with. Fixing these issues helps bring me up to speed on where I’ve been. It also gets me back into the heads of my characters.

Read the last chapter/scene you wrote.

Do basic edits, looking for overused words, typos, continuity errors. This is another way to start thinking “writerly” and it’s giving you that running start for picking up where you left off.

Consult any plot notes.

For me, it’s my idea board, since I don’t outline. I jot things down on sticky notes and slap them onto a foam core board. Filling in details in earlier chapters also helps immerse you in the book.

Figure out the plot points for the next scene.

Once you know what has to happen, based on the previous step, you have a starting point.

Write.

And don’t worry if things don’t flow immediately. Get something on the page. Fix it later.

What about you? Any tips and tricks you’ve found when outside world distractions keep you from focusing?

Now Available: Cruising Undercover

It’s supposed to be a simple assignment aboard a luxury yacht, but soon, he’s in over his head.

Terry Odell is an award-winning author of Mystery and Romantic Suspense, although she prefers to think of them all as “Mysteries with Relationships.”

Terry Odell is an award-winning author of Mystery and Romantic Suspense, although she prefers to think of them all as “Mysteries with Relationships.”

Handwriting Versus Typing

I was listening to a podcast a few years ago that addressed the benefits of handwriting versus typing. The interviewee (I don’t remember her name) was a graduate student who had forgotten to take her laptop to a class one day and had to resort to taking notes by hand. To her surprise, she discovered she had retained more of the lecture information than she normally did. This led to a research project to compare the benefits of the two methods of taking notes.

The memory of that podcast recently prompted a question in my mind: outside of taking notes in class, does anyone write in long hand anymore? If so, what kind of writing lends itself to longhand vs. typing. I found some interesting information online.

***

In a 2021 article on whenyouwrite.com, Jessica Majewski summarized several benefits which I’ve paraphrased here:

Writing by hand is more focused. There are fewer distractions than using a laptop where there are constant temptations to check email or read the latest news story. Also, there are no word processing limitations when writing by hand. The author can draw a mind map, jot side notes, or doodle images without having to open another app.

But typing has its advantages, too. Doing research is a breeze if you’re on your laptop. Just hop over to another app to search out the information you need. Copy and paste articles into your research folder and keep going. But the primary advantage to typing is speed. And sooner or later everything you write is going to have to be typed into a word processor, so unless you’re fortunate enough to have a secretary to do the transition, you’ll have to do the additional work yourself.

But how do the different methods affect creativity? Majewski makes the following case in her article:

“When you are writing by hand, your cognitive processes are more involved than when you type and this can lead to some random springs of ideas. And at the pace of handwriting, you’re not worried about your hands outpacing your brain.”

In a 2017 article on qz.com, Ephrat Livni makes the following statement:

“Brain scans during the two activities also show that forming words by hand as opposed to on a keyboard leads to increased brain activity. Scientific studies of children and adults show that wielding a pen when taking notes, rather than typing, is associated with improved long-term information retention, better thought organization, and increased ability to generate ideas.”

That all sounds good, but does anybody actually write the first draft of a novel by hand? Well, yes. Here are a few authors you may have heard of who have written one or more novels by hand:

- Joyce Carol Oates

- Stephen King

- J. K. Rowling

- Quentin Tarantino

***

As an experiment, I wrote this blog post in long hand. My thoughts flowed as I was writing, and there was a sense of freedom in the process that was different from typing. Fortunately, I was able to read my own handwriting when I finished, and I transferred it to a Word doc.

Well, I’m almost out of paper, so I’ll stop now. We haven’t touched on another creative method: Speech to Text. Maybe we can cover that in a later post.

***

So TKZers – Do you ever write in long hand? What advantages or disadvantages have you noticed using handwriting vs. typing? Has this article convinced you to give handwriting another go?

Creative Marketing: Beyond the Bookstore

Today I’m delighted to introduce a guest post by mystery/suspense author Leslie Budewitz (also writing as Alicia Beckman). Leslie offers ideas about unconventional places to sell books.

Welcome, Leslie!

~~~

Marketing and promotion, it turns out, can require as much creativity as writing itself. One example: launching and selling books through non-traditional outlets, that is, businesses that aren’t primarily bookstores. These outlets are critical for those of us without easy access to bookstores.

When my first novel came out in 2013, the owners of an art gallery in Bigfork, Montana, where I live, approached me with an invitation I could never have imagined, even if I’d written it myself: What about an exhibit called “Bigfork in Paint and Print,” featuring area artists’ visions of the community and a book launch on opening night?

I still remember carrying a box of books into the gallery and finding people waiting for me. People I didn’t know. People who bought multiple copies, for gifts. I sold every book I’d brought and sent my husband home for more. We sold 60 books that night, and another 180 at the local art festival that weekend.

And the gallery? After telling me openings don’t sell paintings so don’t get my hopes up for books, the owners were astonished: They sold nine of eleven paintings that night and a tenth the next week.

Now it helped that I knew the owners, the local paper previewed the event, and the book, Death al Dente, first in my Food Lovers’ Village cozy mysteries, is set in a fictional version of our town. A special case. The exhibit continued for several years and openings were successful, but not at the same level—fewer friends-and-family purchases, more opportunities to buy the books in other places, and a little less excitement.

But this experience showed me the value of non-bookstore outlets.

Does your book have a specific angle that ties in to a local business?

I live in a small tourist town in the northern Rockies. One of the downtown anchor businesses is a kitchen shop. My two cozy mystery series are both set in food-related retail shops, one here and one in Seattle’s Pike Place Market. It’s been a natural combination, and the kitchen shop sells dozens of my books every year to both locals and visitors. To my surprise, it’s also sold more than 100 copies of my first suspense novel, Bitterroot Lake, a hardcover without a single cupcake on the cover. Why? My guess: The bitterroot is the state flower and the word is echoed in landmarks throughout the area, giving it a strong regional appeal.

I live in a small tourist town in the northern Rockies. One of the downtown anchor businesses is a kitchen shop. My two cozy mystery series are both set in food-related retail shops, one here and one in Seattle’s Pike Place Market. It’s been a natural combination, and the kitchen shop sells dozens of my books every year to both locals and visitors. To my surprise, it’s also sold more than 100 copies of my first suspense novel, Bitterroot Lake, a hardcover without a single cupcake on the cover. Why? My guess: The bitterroot is the state flower and the word is echoed in landmarks throughout the area, giving it a strong regional appeal.

You might find a similar connection with an outdoor gear and clothing shop for your books featuring a park ranger or a fishing guide who solves mysteries. Your amateur sleuth runs a coffee cart? I can see the books displayed in the local coffee shop. A café, a brewery, a business built on a local theme—natural connections.

In general, people are not likely to buy a thing in a place where they don’t expect to see it. You probably wouldn’t buy earrings in a convenience store. On the other hand, you might buy a cute pair by a local artist nicely displayed near the cash register. We all love surprises and souvenirs. That’s the whole purpose of gift shops in art centers and historical museums. I’m one of several local authors who sell books through the airport gift shop, an option for those of us who live in smaller cities where airport retail is locally owned and operated.

A few tips: Forge a relationship with the business owner or manager. Show why your book fits their mission and will appeal to their customers. Retailers want new products that will excite their customers.

Offer to accept payment after sales rather than requiring an investment up front. Both the kitchen shop and airport gift shop started by paying me on sales, and quickly moved to buying the books outright.

Personalize an advance copy for the staff to pass around.

Work with the shop on displays. Your book won’t do well where people don’t see it. In the kitchen shop, my books are among the first things visitors see. After my launch at the local art center, I take the small stand-up poster to the kitchen shop and add it to their display. I’ve created a list of books in order, identifying me as a local author and Agatha Award winner. I leave bookmarks. I check in often and fluff the display. I’ve gotten to know the salesclerks, so they talk up my books. And you know that getting other people to talk about your books is more important than anything you can say.

When you make a delivery, find a spot to sit or stand and sign the books you’re leaving. You’ll strike up conversations with customers and staff and sell books while you’re there. Odd as it sounds, sales will go up that day, even after you leave. Every shop and gallery owner I’ve worked with swears it’s true.

Working out the sales percentage may be tricky. Retailers are likely to accept 75/25 because they are used to working on small margins. Nonprofits may be less flexible. If you’re traditionally published and can’t accept 60/40, be prepared to explain why and justify a 75/25 split. Twice recently I’ve heard “We have to treat everyone fairly,” that is, apply the same percentage to all artists. Treating people fairly doesn’t always mean treating them the same, because people aren’t all in the same situation. The only solution I’ve found is to suggest increasing the retail price. I hesitated, thinking an $8 paperback wouldn’t sell at $10, but it has. Remember, gift shop sales are often spur-of-the-moment purchases. You’re not competing with Amazon or B&N; a tourist will see the book as a souvenir, and a local as a special find.

If a shop can do better buying directly, tell them. Some gift shops and used bookstores that carry a few new titles have accounts with Ingram. That’s a better deal for them and easier for you. Stop in regularly to sign books and leave bookmarks.

One-night stands: Even without a regular sales relationship, you can participate in special events at local businesses. Does your book fit with Pioneer Days or other local celebrations? Holiday open houses and “ladies night” events are big opportunities. And if other artists or authors are participating, even better. The “shop and buy” vibe rises exponentially.

Montana authors Mark Leichliter, Christine Cargo, Leslie Budewitz, and Debbie Burke

Finally, though it doesn’t quite fit my theme, I want to mention another option. Create your own event and make it A Thing. When Kill Zone blogger Debbie Burke and her friend Dorothy Donahoe, a retired librarian, took a “get out of Dodge” drive in the summer of 2020, they stopped for lunch at a Bigfork bakery with an outdoor stage and bar and a lovely view. Dorothy suggested Debbie recruit other local authors for a joint event. It’s become an annual event featuring four mystery authors from across the valley.

Find and nurture local connections. People love the idea of promoting local authors; make it easy for them and fun for you. Let your creativity flow beyond the page.

~~~

Thanks, Leslie, for visiting The Kill Zone and sharing these great out-of-the-box ideas. And congratulations on tomorrow’s launch of Blind Faith!

~~~

BLIND FAITH (written as Alicia Beckman), is out October 11 from Crooked Lane Books, in hardcover, ebook, and audio.

BLIND FAITH (written as Alicia Beckman), is out October 11 from Crooked Lane Books, in hardcover, ebook, and audio.

Long-buried secrets come back with a vengeance in a cold case gone red-hot in Agatha Award-winning author Alicia Beckman’s second novel, perfect for fans of Laura Lippman and Greer Hendricks.

A photograph. A memory. A murdered priest.

A passion for justice.

A vow never to return.

Two women whose paths crossed in Montana years ago discover they share keys to a deadly secret that exposes a killer—and changes everything they thought they knew about themselves.

Amazon

Barnes and Noble

Books-A-Million

Bookshop.org

Indie Bound

And your local booksellers!

~~~

Leslie Budewitz is a three-time Agatha Award winner and the best-selling author of the Spice Shop mysteries, set in Seattle, and Food Lovers’ Village mysteries, inspired by Bigfork, Montana, where she lives. The newest: Peppermint Barked, the 6th Spice Shop mystery (July 2022). As Alicia Beckman, she writes moody suspense, beginning with Bitterroot Lake and continuing with Blind Faith (October 2022). Leslie is a board member of Mystery Writers of America and a past president of Sisters in Crime.

The Quadruple-Threat Writer

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

The 20th Century gave us an explosion of legendary entertainers. So many on that list. A sampling in song would have to include Judy Garland, Ella Fitzgerald, Frank Sinatra. Music: Gershwin, Ellington, Glenn Miller. Comedy: Chaplin, Keaton, Laurel & Hardy. Dance: Astaire, Kelly, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson. You can fill in your own favorites.

But there’s one name that deserves to be mentioned here, for he was a quadruple threat: he could sing, dance, and act equally well in comedy or drama. His star flew across stage, screen, TV, and Vegas.

But there’s one name that deserves to be mentioned here, for he was a quadruple threat: he could sing, dance, and act equally well in comedy or drama. His star flew across stage, screen, TV, and Vegas.

His name was Sammy Davis, Jr. (the image capture is Sammy, age 6).

I recall seeing two of his movies as a kid. In Sergeants 3, a 1962 remake of Gunga Din set in the Old West, Davis plays Jonah (the Gunga Din role). He’s the company bugler. At the crucial moment the wounded Jonah crawls up to a cliff to sound an alarm on his bugle, saving the day. I don’t remember any other scene in the movie except that one.

The other movie is Robin and the 7 Hoods, a 1964 musical set in Prohibition-era Chicago. It has Sinatra, Dean Martin, and Bing Crosby. But it’s Davis who steals the show, especially with the song “Bang! Bang!” (again, the one scene I remember).

Davis began as a child-prodigy dancer, and moved easily into singing. His career took off in the 1950s. He made memorable appearances on TV shows—variety, drama, comedy—all the more notable because of two things: the entrenched racism of the time, and the near-fatal car accident that took one of his eyes.

He also battled inner demons, drugs, and alcohol—yet whenever he performed, he gave his all. Audiences knew that.

Which brings me to today’s subject. Are you a quadruple-threat writer?

Can you plot?

I love plot and its mate, structure. We all know there are two preferred methods to go about this. “Discovery writers” find their plot while wearing loose pants. “Plotters” develop it before the journey.

But find it you must, which means driving along Death Road.

The stakes of the plot must be death—physical, professional, or psychological. The road must have certain signposts, the markers of structure. You must know when and how to drive through the Doorway of No Return, stop for a look in the Mirror, and how to race to a surprising and satisfying ending where the reader will thank you and ask when your next book comes out.

Yes, some writers disdain the idea of plotting. I recall an article by a “literary writer” who admitted she was one of these. But then she learned the value of plot, and fell in love with it. Her book sales went up as a result.

Like Sammy Davis, Jr.—learning the basic steps in tap before he could start to set loose with his own style—you can learn the basic elements of plot. I humbly refer you to my book on the subject.

Can you character?

Do you have a Lead worth following? Is your Opposition stronger than the Lead, with a compelling reason to oppose? Are both these characters fresh in surprising ways?

Are the other members of you cast orchestrated—sufficiently different so they may be in potential conflict with everyone else?

Are even your minor characters delightfully distinct to add spice to the plot?

Characterization can be equated with the unique steps a dancer adds in tap. The fresher, the better.

Can you dialogue?

Is your fiction talk crisp? Do the characters use it as a compression and extension of action? Do they have different cadences so they don’t sound the same? Are you skilled at planting exposition and subtext within dialogue?

I’ve long held that dialogue is the fastest way to improve any manuscript. In you first-drafting, it’s where you can really play and improvise, like a great actor might in a scene. Then you can craft it into the kind of fiction talk that gets the attention of readers, agents, and editors.

Can you scene?

Are your scenes structured to include a clear objective, obstacles, and an outcome that is a setback (or a success that leads to a setback)? Do you get into most scenes in medias res (the middle of things) and end them so the reader is prompted to read on? Do you plant mysteries and secrets? Is there tension throughout, even when friends are involved?

Let’s watch an example.

This is Sammy in his last performance, in the joyous movie Tap. At this time he had the throat cancer that would kill him just a year later. Yet here he is, going toe-to-toe with the late, great Gregory Hines. The setup: a group of aging tap dancers live together in a combo rooming house and dance studio run by Mo (Davis). Max (Hines), just out of prison, comes for a visit. He and Mo get into some banter over dance style, when Max shades him with, “You ain’t got no legs.” Mo takes that as a “challenge.” A challenge is when all the tappers get together and try to outdo one another. Mo calls the oldsters in for the challenge. The subtext is that Mo is sick, and is not supposed to dance anymore. This is enforced by Mo’s daughter, Amy (Suzanne Douglas), who conveniently is not around. Every one of these tap dancers, in their 70s and 80s, are legends of the form, from Howard “Sandman” Sims to Harold Nicholas (not to mention another prodigy, young Savion Glover, watching). They proceed to strut their stuff, and oh, what stuff it is!

And then, at the end, Sammy Davis, Jr., the quadruple-threat entertainer, gives his all one last time:

Get proficient in plot, characterization, dialogue, and scenes. Then you, too, will become a master tapper…of the keyboard! You’ll be a quadruple-threat writer.

Writing Strategies

Writing Strategies: Breaking through writer’s block, keeping your butt in the writing chair, and rewiring your brain

The Kill Zone is a goldmine of advice and insight on all aspects of writing and publishing, from how to write and ways to publish, to creating characters, embracing story structure, and much more.

Getting to the keyboard to write, and once there, continuing to write is a challenge for many of us, especially with the internet ready to provide endless distractions. Today’s Words of Wisdom shares three excerpts from the KZB archives that provide ideas and strategies to help get past writer’s block and keeping motivated. You can read the full post for each excerpt via the date links. It’s also an entirely unintentional, serendipitous follow-on to James Scott Bell’s Reader Friday post yesterday entitled “Setting Yourself on Fire.”

So, the table has been set for today’s discussion. Feel free to comment and engage with other readers on any, or all, of these topics.

I was feeling uninspired in my writing (which probably explains why I was surfing the Internet and reading about placebo studies). So I wondered: If a placebo can cure cranky bowels, could it help me break through a minor case of writer’s block?

I decided to run my own unscientific study. I didn’t have any sugar pills on hand, so I reached for the next best thing: my daughter’s jelly beans. I figured that labeling and ritual had to be part of the reason why placebos work, so I poured the jb’s into an empty prescription container. (And I have to report that jelly beans look extremely potent when they’re staring up at you from a bottle of blood thinner medication.) Then I put a nice label on it marked “Creativity.”

As part of my morning ritual I started taking two “creativity pills” with my coffee. As I solemnly popped the beans, I paused to meditate for a few moments about my writing goals for the day.

And by God, it worked. I blasted right through that writer’s block. I wrote four pages that day, and haven’t looked back since.

The only thing is, now I’m afraid to stop taking the beans. I think I’m hooked. For my next batch I’m thinking of getting those special-order M&Ms–the ones you can order with little messages written on them. I’ll get them labeled with something like, “Writing is rewriting,” or whatever fits.

What about you? Do you have any silly rituals that help you get your creativity engine going?

–Joe Moore, January 11, 2011

I like to reexamine what tips I would give to aspiring authors, or even experienced authors, when I get a chance to speak to a group. Invariably the question comes up on advice and I’ve noticed that what helps me now is different than what I might have found useful when I started. Below are 8 tips I still find useful. Hope you do too, but please share your ideas. I’d love to hear from you.

1.) Plunge In & Give Yourself Permission to Write Badly – Too many aspiring authors are daunted by the “I have to write perfectly” syndrome. If they do venture words onto a blank page, they don’t want to show anyone, for fear of being criticized. They are also afraid of letting anyone know they want to write. I joined writers organizations, took workshops, and read “how to” articles on different facets of the craft, but I also started in on a story.

2.) Write What You Are Passionate About – When I first started to write, I researched what was selling and found that to be romance. Romance still is a dominant force in the industry, but when I truly found my voice and my confidence came when I wrote what I loved to read, which was crime fiction and suspense. Look at what is on your reading shelves and start there.

3.) Finish What You Start – Too many people give up halfway through and run out of gas and plot. Finish what you start. You will learn more from your mistakes and may even learn what it takes to get out of a dead end.

4.) Develop a Routine & Establish Discipline – Set up a routine for when you can write and set reasonable goals for your daily word count. I track my word counts on a spreadsheet. It helps me realize that I’m making progress on my overall project completion. Motivational speaker, Zig Ziglar, said that he wrote his non-fiction books doing it a page a day. Any progress is progress. It could also help you to stay offline and focused on your writing until you get your word count in. Don’t let emails and other distractions get you off track.

–Jordan Dane, August 7, 2014

Rewiring the brain

In an article published in WD in 2012, Mike Bechtle argued that mere willpower is not the most effective solution for breaking through writer’s block. He suggests that we rewire our brains to get back into the “flow”.

Here were my major takeaways from Bechtle’s article:

- Write first thing in the morning, when alertness and energy levels are typically at their highest. (My note: If you can’t write first thing in the morning, try to write at the same time of day every day. Your brain will “learn” to kick into gear at its regular writing time)

- Fuel your brain with a nourishing breakfast (Think eggs and fruit, not an apple fritter)

- Limit distractions (Don’t check email or messages before writing, and don’t read a newspaper, turn on the TV, or listen to radio, either)

- Keep writing sessions short (The brain can focus intensely for only short periods of time, according to Bechtle)

- Apply glue to butt (Stay seated while writing, that is!)

- Don’t set your expectations too high

Other strategies

In my first foray as a fiction writer back in the 90’s, I was a contract writer for the Nancy Drew series. The schedule for those books gave me little leeway for writer’s block. As soon as the chapter outline was approved, writers were given six weeks to complete the novel. Six weeks! I had to write those stories so fast, I felt as if I was hurling words at the word processor. Every project was a race to the finish line. “Writer’s block” was a foreign concept.

Then my editor left, and the publishing landscape changed. I stopped writing NDs and began to vaguely contemplate writing something on my own. Inertia quickly set in. Months became years, and I hadn’t written anything new.

15 minutes a day, that’s all we ask

I happened to read an article by Kate White, who is an author and former editor of Cosmopolitan Magazine. Her advice to getting started? Write 15 minutes per day, first thing in the morning. No. Matter. What.

To act on Kate’s suggestion, I had to set my alarm for five a.m. instead of six. That extra hour gave me enough time to down a cup of coffee and generate 15 minutes of quality writing time, before I headed off to my day job.

White’s advice worked for me. Fifteen minutes of writing daily eventually became an hour. Soon I was producing a minimum quota of a page a day. (Yes, I know: a single page a day isn’t impressive as a quota. See the last bullet point of the previous list about lowering expectations.) A few months later, I had completed the first draft of my new novel.

Kathryn Lilley, June 16, 2015

***

Now it is your turn.

- Do you have tips for breaking through a minor writer’s block?

- How do you keep yourself writing?

- Do you have a routine you use, or a ritual?

- Any advice on keeping your keister in the writing chair?

Reader Friday: Setting Yourself on Fire

Celebrating Others’ Success

Celebrating our success is a must. A little reward for a job well done is vital to keep motivated (and happy and healthy) in this difficult writing business. It doesn’t have to be much—just enough of a kickback to make it worthwhile.

It’s one thing to celebrate our personal achievement. It’s a whole other level to get satisfaction from celebrating others’ success. And it’s something we, as a collective writer community, should do more of. Celebrate others’ success.

What brought-on this post is Sue Coletta’s most recent success. Sue was the top-selling author at her publishing house in September. I can think of no other person who is as dedicated to their craft as Sue. And it paid off. Well done, Sue!

Recognizing success doesn’t have to be in the writing world. My friend just celebrated a blue ribbon at the fall fair won by her huge butternut squash. It weighed-in at 37.25 lbs. Sure, it’s a long way off the world record of 65.5 lbs., but it’s an impressive big gourd. Totally organic, to boot. It was grown through her neighbor’s organically-fed hens’ manure.

Our 34-year-old daughter’s success is impressive, as well. Emily recently packed up and moved to Ecuador where she’ll continue her online writing business as a digital nomad. So, congrats on your courage and adventuresome spirit, Em. OPD’s proud of you, and I celebrate your successful move! (BTW—OPD stands for Over Protective Dad which she nicknamed me in her teens.)

No. it isn’t only writing, moving, or squash growing success to celebrate. On a large scale, I celebrate NASA for bulls-eyeing an asteroid some zillion miles away. I celebrate the Ukrainian people’s resolve to repel an invader. And I celebrate Aaron Judge for hitting 62 homers this season.

On a smaller scale, I celebrate someone else’s success. That was the couple in my home town who stood up to City Hall and won the court-approved right to keep a noisy rooster in their backyard coop. That rooster services the organically-fed hens in my friend’s neighbor’s yard whose poop helped her score the blue ribbon.

What about you Kill Zoners? Tell us how you’ve celebrated others’ success.

Fire in the hole!

Full disclosure: I’m cheating again. I owe a book to my publisher on October 15, and it gets all my attention for a while. So, I decided I’d test everyone’s patience by recycling a post from January, 2017, in which I wrote about one of my favorite topics, which is things that go boom. I’m confident that the laws of physics and chemistry have not changed in the past five years, so the content should still be reliable. Here we go . . .

I’m going to continue my quest to help writers understand some of the technical aspects of weaponry so that their action scenes can be more realistic. Today, we’re going to talk about some practical applications for high explosives. It’s been a while since we last got into the weeds of things that go boom, so if you want a quick refresher, feel free to click here. We’ll wait for you.

Welcome back.

When I was a kid, the whole point of playing with cherry bombs and lady fingers and M80s was to make a big bang. Or, maybe to launch a galvanized bucket into the air. (By the way, if you’re ever tempted to light a cherry bomb and flush it down the toilet, be sure you’re at a friend’s house, not your own. Just sayin’. And you’re welcome.) As I got older and more sophisticated in my knowledge of such things, I realized that while making craters for craters’ sake was deeply satisfying, the real-life application of explosives is more nuanced.

Since TKZ is about writing thrillers and suspense fiction, I’m going to limit what follows to explosives used as weapons–to kill people and break things. Of course, there are many more constructive uses for highly energetic materials, and while the principles are universal, the applications are very different.

Hand grenades are simple, lethal and un-artful bits of destructive weaponry. Containing only 6-7 ounces of explosive (usually Composition B, or “Comp B”), they are designed to wreak havoc in relatively small spaces. The M67 grenade that is commonly used by US forces has a fatality radius of 5 meters and an injury

only 6-7 ounces of explosive (usually Composition B, or “Comp B”), they are designed to wreak havoc in relatively small spaces. The M67 grenade that is commonly used by US forces has a fatality radius of 5 meters and an injury  radius of 15 meters. Within those ranges, the primary mechanisms of injury are pressure and fragmentation.

radius of 15 meters. Within those ranges, the primary mechanisms of injury are pressure and fragmentation.

For the most part, all hand grenades work on the same principles. By pulling the safety pin and releasing the striker lever (the “spoon”), the operator releases a striker–think of it as a firing pin–that strikes a percussion cap which ignites a pyrotechnic fuse that will burn for four or five seconds before it initiates the detonator and the grenade goes bang. It’s important to note that once that spoon flies, there’s no going back.

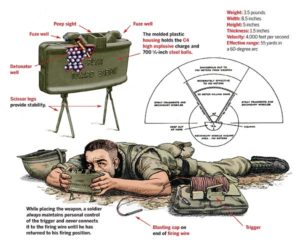

Claymore mines operate on the same tactical principle as a shotgun, in the sense that  it is designed to send a massive jet of pellets downrange, to devastating effect. Invented by a guy named Norman MacLeod, the mine is named after a Scottish sword used in Medieval times. Unlike the hand grenade, which sends its fragments out in all directions, the Claymore is directional by design. (I’ve always been amused by the embossed letters on the front of every Claymore mine, which read, “front toward enemy.” As Peter Venkman famously said while hunting ghosts, “Important safety tip. Thanks,Egon.”)

it is designed to send a massive jet of pellets downrange, to devastating effect. Invented by a guy named Norman MacLeod, the mine is named after a Scottish sword used in Medieval times. Unlike the hand grenade, which sends its fragments out in all directions, the Claymore is directional by design. (I’ve always been amused by the embossed letters on the front of every Claymore mine, which read, “front toward enemy.” As Peter Venkman famously said while hunting ghosts, “Important safety tip. Thanks,Egon.”)

The guts of a Claymore consist of a 1.5-pound slab of C-4 explosive and about 700 3.2 millimeter steel  balls. When the mine is detonated by remote control, those steel balls launch downrange at over 3,900 feet per second in a 60-degree pattern that is six and a half feet tall and 55 yards wide at a spot that is 50 meters down range.

balls. When the mine is detonated by remote control, those steel balls launch downrange at over 3,900 feet per second in a 60-degree pattern that is six and a half feet tall and 55 yards wide at a spot that is 50 meters down range.

The fatality range of a Claymore mine is 50 meters, and the injury range is 100 meters. (Note that because of the directional nature of the Claymore, we’re noting ranges, whereas with the omnidirectional hand grenade, we noted radii.)

Both the hand grenade and the Claymore mine are considered to be anti-personnel weapons. While they’ll certainly leave an ugly dent in a car and would punch through the walls of standard construction, they would do little more than scratch the paint on an armored vehicle like a tank. To kill a tank, we need to pierce that heavy armor, and to do that, we put the laws of physics to work for us.

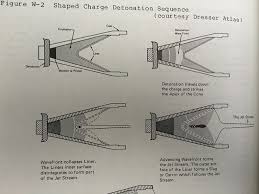

Shaped charges are designed to direct a detonation wave in a way that focuses  tremendous energy on a single spot, thus piercing even heavy armor. The principle is simple and enormously effective.

tremendous energy on a single spot, thus piercing even heavy armor. The principle is simple and enormously effective.

The illustration on the left shows a cutaway view of a classic shaped charge munition. You’re looking at a cross-section of a hollow cone of explosives. Imagine that you’re looking into an empty martini glass where the inside of the glass is made of cast explosive that is then covered with a thin layer of metal. The explosive is essentially sandwiched between external and internal conical walls. The open end of the cone is the front of the munition.

The initiator/detonator is seated at the pointy end of the cone (the rear of the munition), and when it goes off, a lot happens in the next few microseconds.  As the charge detonates, the blast waves that are directed toward the center of the cone combine and multiply while reducing that center liner into a molten jet that is propelled by enormous energy. When that jet impacts a tank’s armor, its energy transforms the armor to molten steel which is then propelled into the confines of the vehicle, which becomes a very unpleasant place to be. The photo of the big disk with the hole in the middle bears the classic look of a hit by a shaped charge.

As the charge detonates, the blast waves that are directed toward the center of the cone combine and multiply while reducing that center liner into a molten jet that is propelled by enormous energy. When that jet impacts a tank’s armor, its energy transforms the armor to molten steel which is then propelled into the confines of the vehicle, which becomes a very unpleasant place to be. The photo of the big disk with the hole in the middle bears the classic look of a hit by a shaped charge.

Now you understand why rocket-propelled grenades like the one in the picture have such a distinctive shape. The nose cone is there for stability in flight, and it also houses the triggering mechanisms.

Now you understand why rocket-propelled grenades like the one in the picture have such a distinctive shape. The nose cone is there for stability in flight, and it also houses the triggering mechanisms.

The picture on the right is a single frame from a demonstration video in which somebody shot a travel trailer with an RPG. The arrow shows the direction of the munition’s flight. There was no armor to pierce so the videographer was able to capture the raw power of that supersonic jet of energy from the shaped charge.

The picture on the right is a single frame from a demonstration video in which somebody shot a travel trailer with an RPG. The arrow shows the direction of the munition’s flight. There was no armor to pierce so the videographer was able to capture the raw power of that supersonic jet of energy from the shaped charge.

Looming deadline notwithstanding, I will do my best to answer any and all questions, but I warn you all that I might be a bit slow on the keyboard.

“Success is not the result of spontaneous combustion. You must set yourself on fire.” – Reggie Leach, retired Canadian hockey player.

“Success is not the result of spontaneous combustion. You must set yourself on fire.” – Reggie Leach, retired Canadian hockey player.