by Debbie Burke

Fiction writers play with imaginary friends whenever we create characters. We put them in a pickle and see what they do; pile insurmountable challenges on them; make them fall in and out of love; tie them to the railroad tracks and see how they free themselves. They become as close and familiar as our own family and friends.

We design how they look—short, tall, slender, heavyset, muscular, flabby. Choose the color of their skin, hair, and eyes. Grow a beard or mustache. Add scars, tattoos, piercings.

Some authors cut out photos from magazines to use as their models. Or they draw parallels to real-life actors, musicians, celebrities, or politicians in the news.

Others prefer to keep descriptions minimal. They paint a general picture but let the reader fill in the fine details.

I lean toward minimalist but have an image in my mind. Often that vision shifts in the course of a story because of plot needs.

The main character in my series, Tawny Lindholm, is a fiftyish recent widow. She’s smart but also naïve and too trusting because of her sheltered life in small-town Montana. As the story unfolded, I piled on more flaws that enhanced important parts of the plot and themes.

She’s far-sighted and can’t read small print without glasses—also a metaphor for her initial blindness to danger.

Her meniscus is torn, which hampers fleeing from bad guys.

I broke the poor woman’s finger (how cruel, right?), which caused arthritis and permanent swelling. That injury means she can’t remove her wedding ring and becomes part of her personality, tying in the theme of mourning and loyalty to her late husband. More importantly, that seemingly insignificant detail served as a key element in the plot, proving her innocence.

Have you ever experienced a character who shows up in real life, as if s/he had just stepped out of your computer screen? Recently, that’s happened twice to me in a couple of unlikely places.

First incident: my car needed new tires. The manager at Les Schwab was fiftyish, dark hair, barrel-chested, and muscular. He wore a blue uniform with his name on the pocket, hands a little dirty from showing tires to customers and helping out in the shop. His brown eyes twinkled with an inside joke he couldn’t wait to share. Although we kidded around as he wrote up my tire purchase, he was professional and business-like.

I don’t remember his real name because, to me, he was Dwight, Tawny’s dead husband. Through the series, Dwight occasionally appears in her memories with a joke or snippet of conversation.

Waiting time to install new tires was two hours. I grabbed a cup of coffee and a free bag of popcorn—at Les Schwab stores, you hardly smell the rubber because the popcorn aroma greets you as soon as you walk in the door (popcorn and coffee have since been discontinued since COVID-19). I settled in at a tall table, pretended to read a magazine, and did what writers love to do—people-watch and eavesdrop.

For two hours, I watched the real-life Dwight interact with other patrons, tire busters, and people on the phone. He was patient and polite with cranky customers, and firm but even-tempered when screw-ups happened in the shop. That twinkle in his brown eyes never wavered.

Not only did his appearance and manner exactly match the Dwight of my imagination, so did his personality. It was eerie but also thrilling.

Second incident: This happened in February while vacationing in Florida. When I’m there, I attend Zumba classes and, over several years, have gotten to know a number of regulars. I’m happy to reconnect with them because they’re loyal fans of my thriller series, bringing copies for me to sign, inviting me to talk to their book clubs, and eagerly asking when the next book will be out. They are terrific supporters for whom I’m very grateful.

One morning, I spotted a new woman in class—tall, willowy, with long red hair in a ponytail and a bright smile.

Tawny, my protagonist, in the flesh.

The woman must have thought I was weird because, for the next hour, I watched her instead of the instructor. After class, we chatted about dancing. She felt intimidated because it was her first time but she was game and didn’t give up. Persistence and determination are two major personality traits Tawny has and this lady checked off those boxes. She was also friendly, open, spirited, and a good listener. Check off more boxes.

After several minutes of conversation, I worked up the courage to tell her I was a writer and explained I’d been staring at her because she looked like the heroine in my books. Instead of being creeped out by a crazy old lady Zumba stalker, she was excited. A dozen other people who’d read the series also noticed the resemblance, affirming, “Yes! She does look just like Tawny.”

Her real name is Kim, a massage therapist from Minnesota and she was eager to read about her alter ego.

In #1, Tawny receives a confusing new smartphone that she believes is a gift from her son. The Instrument of the Devil actually came from the villain who tampered with the device as part of a terrorist plot. Tawny blames herself for the phone’s peculiar behavior when, in fact, he rigged it to stalk her and eavesdrop.

At the next Zumba class, Kim had read the first few chapters and said, “I totally identify with her struggles with the smartphone.”

As do all of us born before 1990!

A few days later, she finished the book and said, “She’s so much like me it’s giving me chills.”

That comment gave me chills.

As authors, connecting with readers is our best reward. But connecting in real life with characters we thought only lived in our imaginations is a close second.

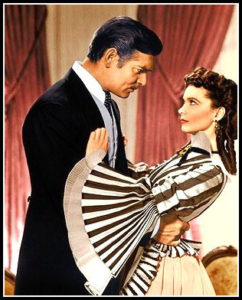

This gracious doppelganger agreed to pose for a photo. Heeeeere’s Tawny!

A big thank you to Kim for being an inspiration. She’s also a great sport as I continue to make her life miserable in the next books, Stalking Midas and Eyes in the Sky.

~~~

TKZers: Has a character ever stepped out of your book into real life? What happened? Did their appearance match their personality? How were they different from what you envisioned?