Image by Andreas Lischka from Pixabay

When I was finally able to travel after my vaccinations earlier this month, I visited my mom. She’s 95 and has cognitive issues. (And vision issues, and hearing issues, but she’s 95 and has survived COVID.) Carrying on a conversation with her is a challenge. She’ll ask a question, you’ll answer, and a minute later, she’ll ask the same question. It doesn’t take long before you feel like you could record your answer and set it to play back while you go do something else. Of course, she has no idea she’s repeating herself.

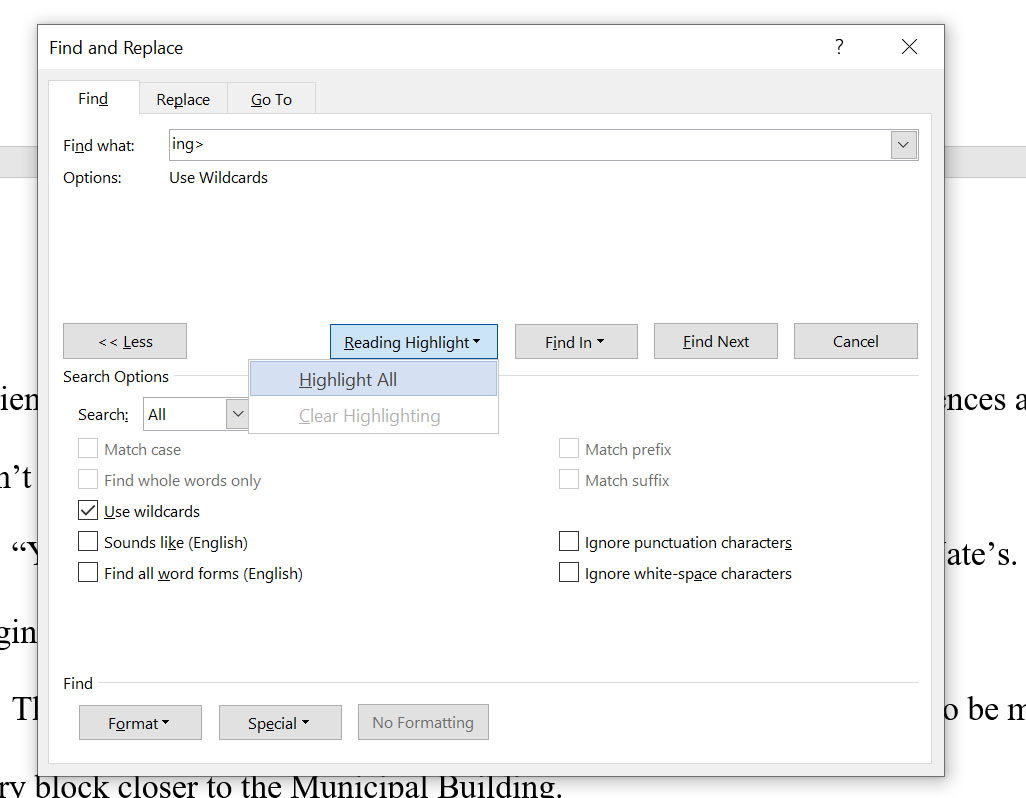

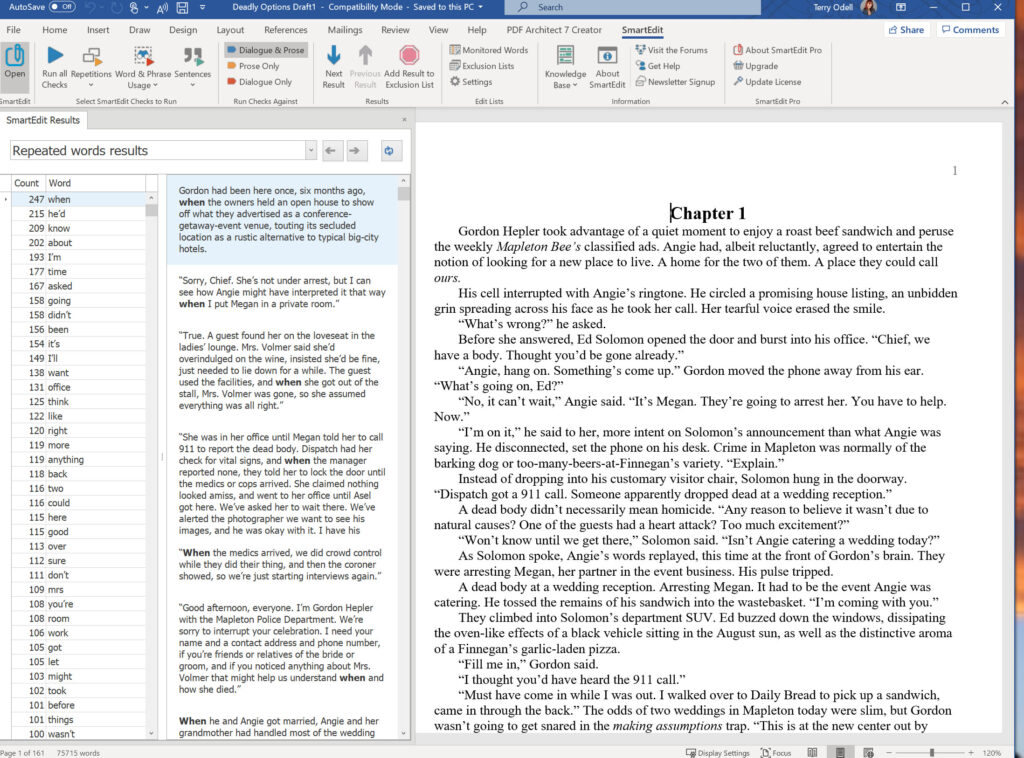

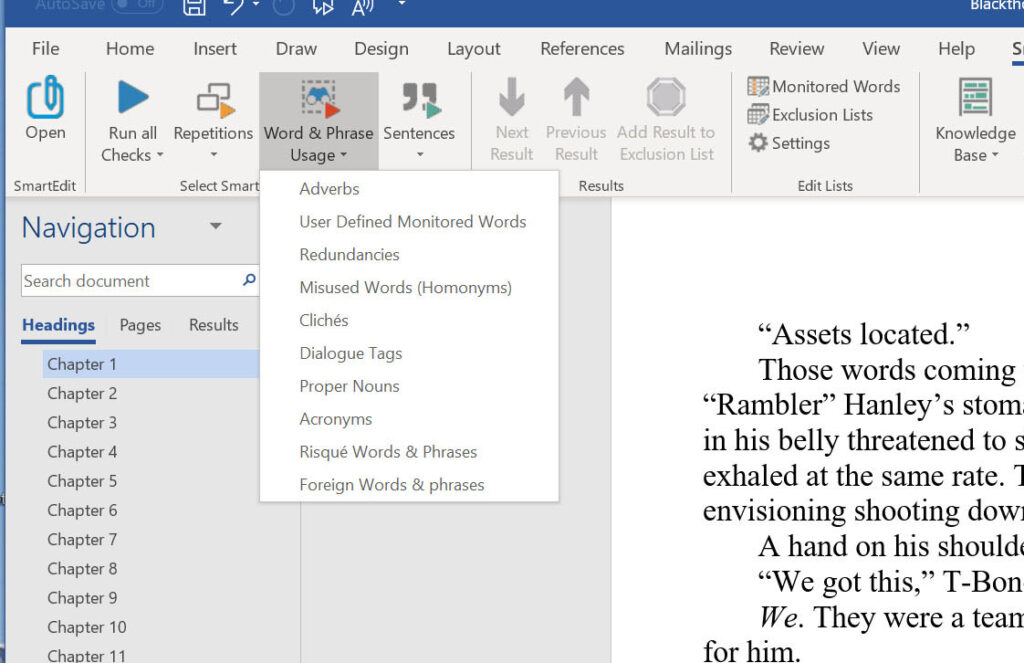

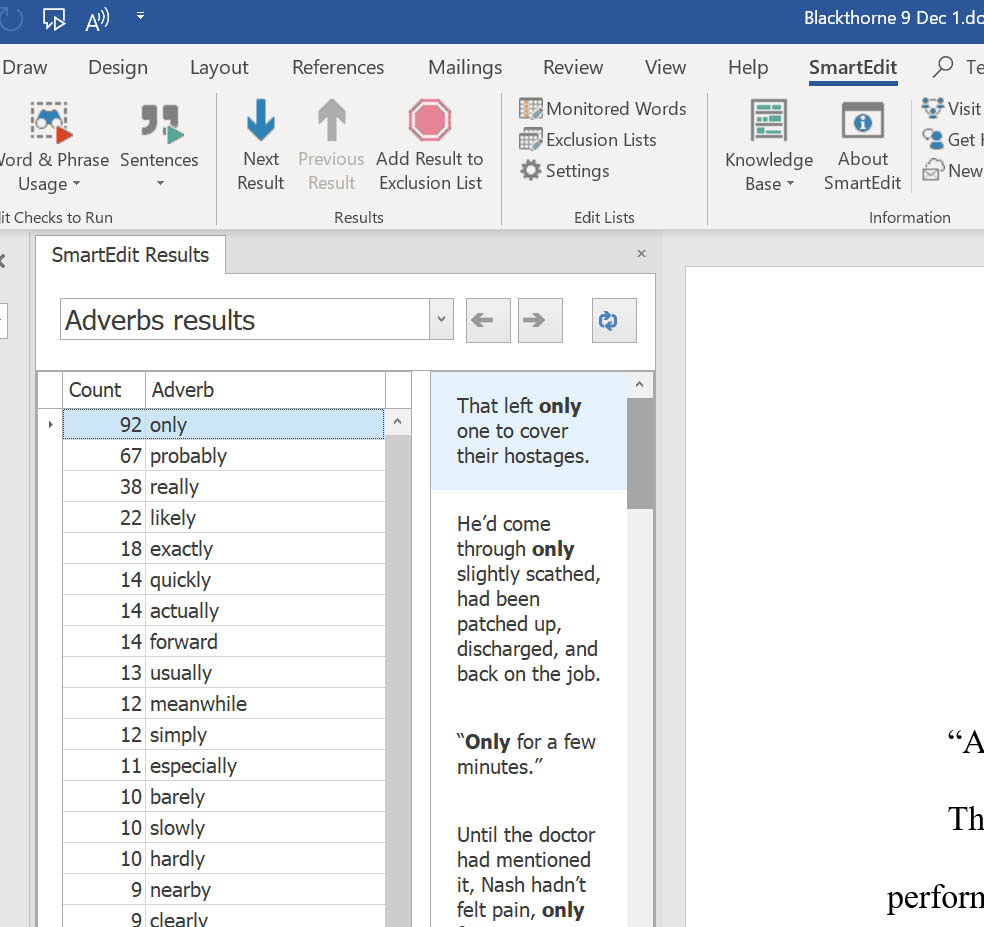

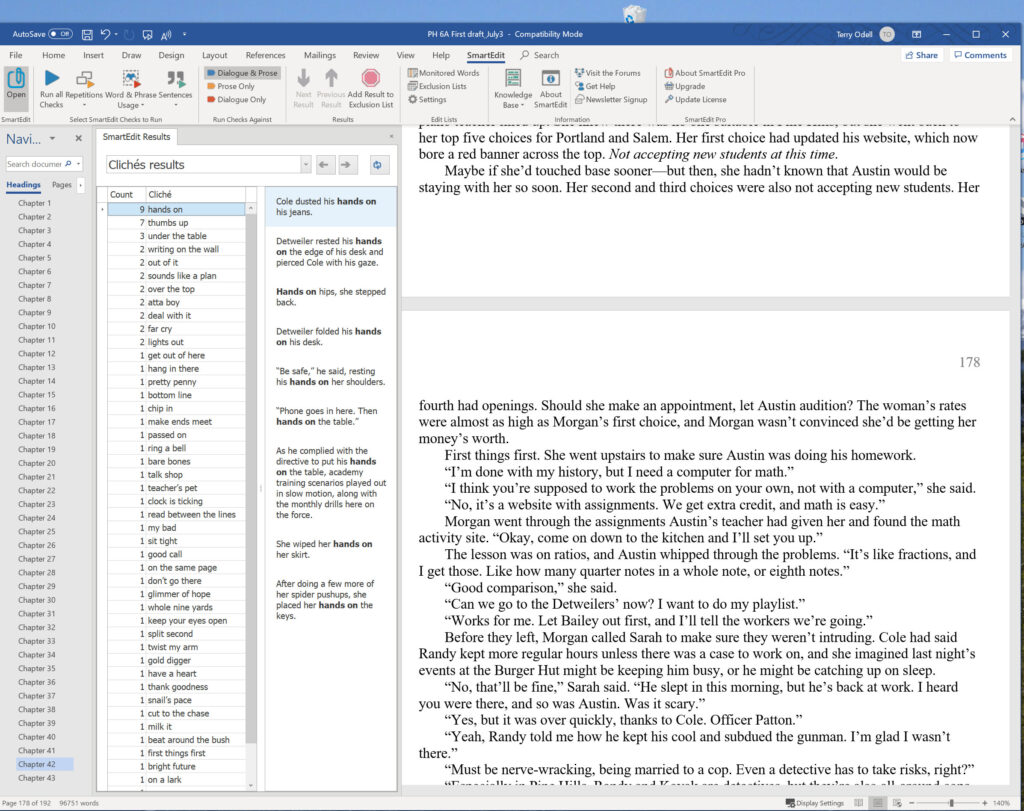

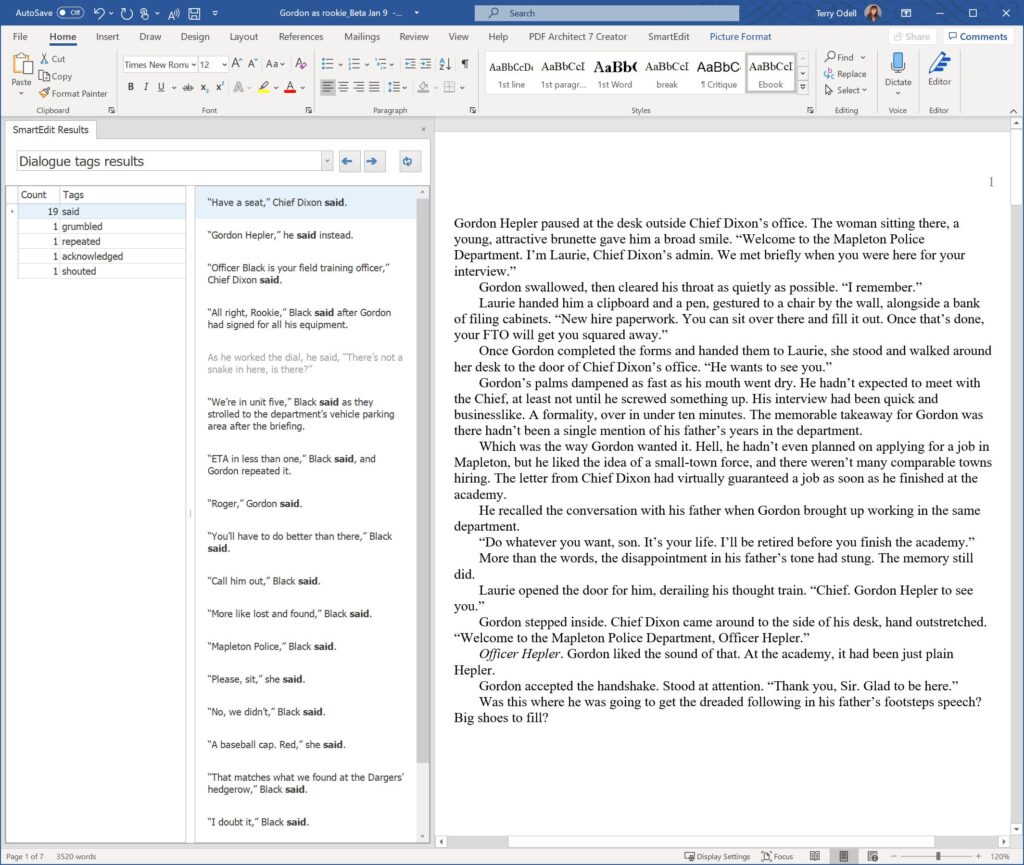

Repetition is something to watch out for in our writing as well. One lesson learned early on was, “Don’t tell readers something they already know.” But, as writers, we often want to make sure our readers understand a point we’re making, and we repeat it. But when is it too much? What’s the best way to handle it?

An extreme example: A long time ago, in one of my first critique groups, one author’s character was an activist, giving speeches all over the country. The author had done a good job of writing the speech and the readers ‘heard’ it all on the page (or several pages, as I recall). But then, when the character made the next stop, the author repeated the entire speech verbatim. You can imagine that by the third or fourth delivery of the speech, the reader was tuning out. Now, the author was also adding some new material to the speech, but would the reader stick with it to get to the end of the already way-too-familiar territory to see what was added? Probably not. The group suggested that the only thing the author needed to show was the new stuff.

An extreme example: A long time ago, in one of my first critique groups, one author’s character was an activist, giving speeches all over the country. The author had done a good job of writing the speech and the readers ‘heard’ it all on the page (or several pages, as I recall). But then, when the character made the next stop, the author repeated the entire speech verbatim. You can imagine that by the third or fourth delivery of the speech, the reader was tuning out. Now, the author was also adding some new material to the speech, but would the reader stick with it to get to the end of the already way-too-familiar territory to see what was added? Probably not. The group suggested that the only thing the author needed to show was the new stuff.

I’ve been seeing the same issues in a series of mystery novels I’ve been reading. Cop Bob interviews a suspect, Jim. Then, when he reports to his partner—let’s call her Mary—he repeats all the information he’s gleaned. Skim time.

If you’re writing multiple points of view, any time your POV characters are separated, only one of them knows what’s going on. If you’re in a Bob POV scene, it’s easy enough to handle. But what if you’re Mary’s POV when Bob tells her what Jim said? You don’t want to repeat the conversation. AND, you don’t want to repeat the same plot points from the previous scene. No matter what the “rules” say, there’s nothing wrong with telling in order to get information to the reader—it’s when the telling becomes back story dumping that you’ll run into problems.

You need to move things forward. You can recap in narrative in a few words. “Mary listened as Bob told her Jim had admitted to being in the shop when the robbery took place. She cut him off before he went into every detail about who else had been there, and who bought what.”

Start your showing from there, dealing with the critical plot points for this particular scene.

An example from In Hot Water, one of my Triple-D Ranch romantic suspense books. In the genre, it’s expected to have alternating POVs. Here, the heroine, Sabrina, isn’t always with Derek, the hero. When the hero’s scene has him learning about a possible attack on his ranch, he and his team go over the possible ramifications, discuss plans of action. Now, when Sabrina gets her POV scene, the reader already knows all of this. But in her POV, she’s learning all new stuff. She needs to be brought up to speed. There will have to be some repetition, but it’s also important to have her add something to the mix. Does she bring up a point the guys didn’t think of? (One hopes so!) Is this attack going to affect her differently than it does the men? Show that.

Another aspect of repetition is to remind readers of things they might have forgotten, especially if they’re going to be important later. Did you foreshadow it? How long has it been since this information was relayed to the reader? Do they need a reminder? After all, much as an author hates to admit it, readers don’t always sit down with a book and read from page one to the end in a single sitting.

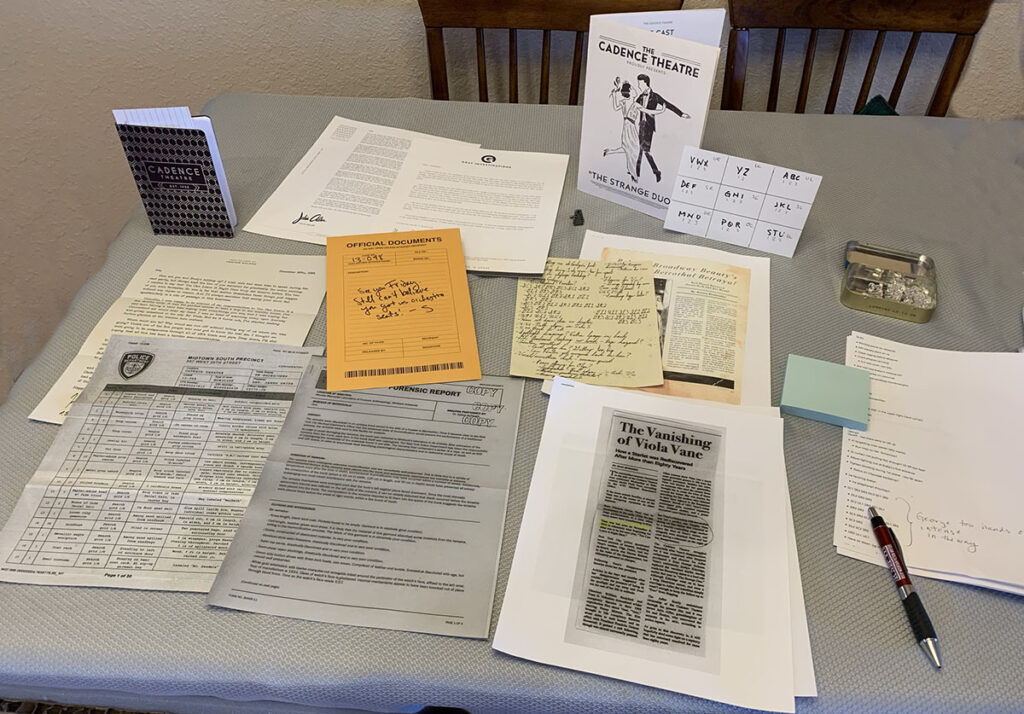

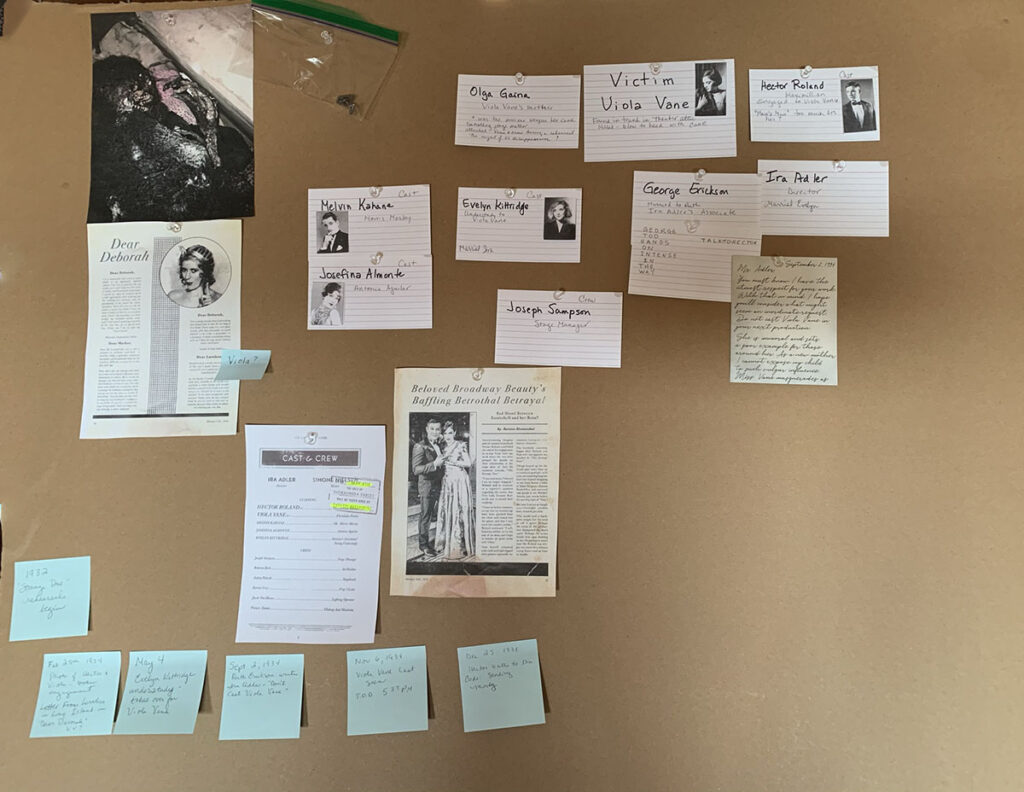

In a mystery, the cops/detectives are going to be reviewing the case, recapping old information along with introducing new facts. This can help the readers remember. It also lets the author sneak in red herrings and hide the “real” clues in plain sight.

Bottom line: Give the information in a new way. Add something new beyond straight repetition. Keep moving the story forward.

Terry Odell is an award-winning author of Mystery and Romantic Suspense, although she prefers to think of them all as “Mysteries with Relationships.” Follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

Are Gordon’s Days in Mapleton Numbered?

Deadly Options, a Mapleton Mystery/Pine Hills Police crossover.

What’s the biggest surprise a character has thrown at you while writing (or plotting) a book?

What’s the biggest surprise a character has thrown at you while writing (or plotting) a book?

What is author branding? When I attended a SleuthFest conference, one of the invited guests was Neil Nyren, a top gun at Penguin Putnam. I did a workshop on Point of View, and served on several panels. My latest releases that year were my three Triple-D Ranch books, and when I was “working” I wore my cowboy boots and hat. (I live in Colorado: the boots are my dress shoes, and the hats are common attire.)

What is author branding? When I attended a SleuthFest conference, one of the invited guests was Neil Nyren, a top gun at Penguin Putnam. I did a workshop on Point of View, and served on several panels. My latest releases that year were my three Triple-D Ranch books, and when I was “working” I wore my cowboy boots and hat. (I live in Colorado: the boots are my dress shoes, and the hats are common attire.)

I know this topic was mentioned recently, and apologies for not being able to find the post to credit the author. Perhaps it came up in the comments. No matter the source, I thought this craft topic worth another look, especially after a recent read.

I know this topic was mentioned recently, and apologies for not being able to find the post to credit the author. Perhaps it came up in the comments. No matter the source, I thought this craft topic worth another look, especially after a recent read.