Reader Friday: What Would You Watch?

What book published in the last year have you read that you would like to see adapted for streaming?

(HT to Joe Hartlaub for the suggestion.)

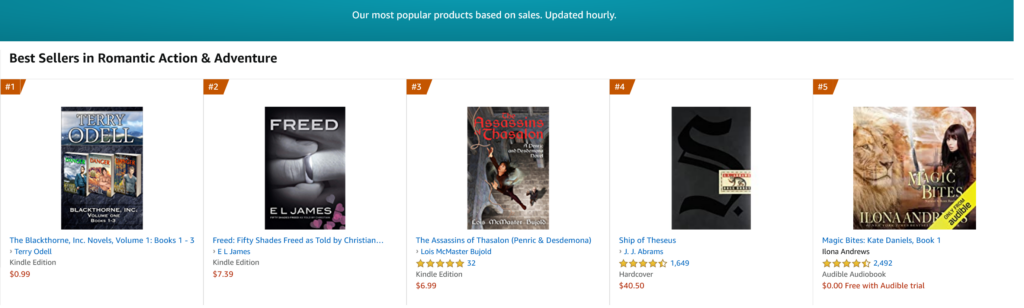

Who’s A Best-Selling Author?

Terry Odell

Can you read those “Best Seller” banners at the top of the book images? Those were put there by Amazon and Barnes & Noble, not me.

Pretty impressive, right?

I should rush right out and change all my book covers so they proclaim my status. Plaster it on my website, add it to my email signature line.

But let’s step back and be realistic.

A while back, I attended a conference workshop on becoming a best-selling author, thinking I might pick up a few tips. Nothing she said was anything different than advice I’d already heard dozens of times. When I walked out was when the presenter said that if you could be in the top 100 on an Amazon genre list, you could promote yourself as a best-selling author. Note: she said “Genre List,” not overall sales. Another route was to make the top 100 in a Genre list on Amazon’s “New Releases page.”

Yes, I got those banners from Barnes & Noble and Amazon. But how?

I was fortunate to garner a BookBub Featured Deal promotion slot. For which I paid a pretty penny, mind you. Getting the BookBub acceptance is as much luck as it is having a first-rate product. They hold their algorithm cards close to the vest, but I’m convinced a lot has to do with timing, how much of a price drop you’re willing to take, and maybe reviews, although they’ll be the first to point out that many of their deals have very few reviews. In this case, my submission was for a 3-book set. The set itself didn’t have many reviews, but the individual books did, and one had won a respected award. But, it could just as easily have been numbering all the submissions in any given genre and using a random number generator to pick.

So, for one day, my Blackthorne Inc. Novels, Volume 1 was featured in the BookBub newsletter. Sales skyrocketed, which is the usual case. Not a huge moneymaker, since I’d dropped the price to 99 cents, which lowers the royalty rate (except at Nook, which pays 70% regardless of price).

Because those skyrocketing sales brought the book to #1 in 3 sub-genres, they garnered me those Best Seller banners.

Do I consider myself a best-selling author? Did I write a best-seller? No. One day’s sales, stimulated by an ad, are not my criteria for touting myself as a best-selling author. Yet I’m fully aware that there are those out there who would milk those banners for everything they’re worth.

Do I consider myself a best-selling author? Did I write a best-seller? No. One day’s sales, stimulated by an ad, are not my criteria for touting myself as a best-selling author. Yet I’m fully aware that there are those out there who would milk those banners for everything they’re worth.

Realistically, when I see an author I’ve never heard of touting themselves as ‘best-selling’ authors, I’m going to look up their books on Amazon. When I see that they’re ranked in the hundreds of thousands—or, in some cases, millions, I have to wonder. Odds are, they’re looking at a fleeting moment of good sales/rankings based on an ad. And that they received that ranking for a relatively obscure genre, not overall sales.

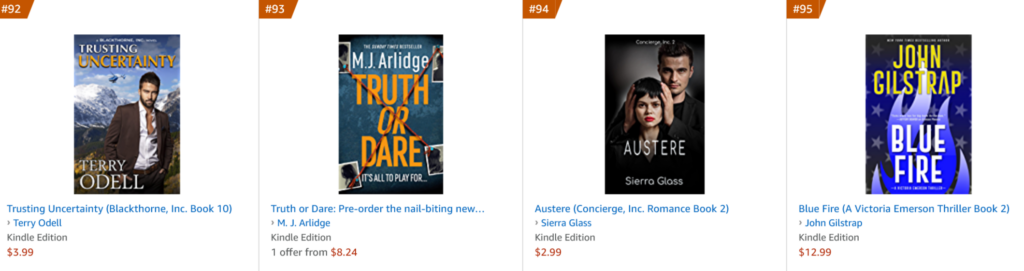

And popping back to that workshop where making the top 100 in “New Releases” was grounds for declaring oneself a best-selling author? I have a new release coming out this summer. I put it up for preorder and used BookBub for a pre-order ad. These are different from Featured Deals, and are dirt cheap in comparison. The flip side is they go only to your BookBub followers who agree to notification, so it’s a teeny-tiny pool relative to their regular newsletter. (At least it is for me, since I don’t have that many followers on BookBub.) On a positive note, when you’re a tiny fish in a big ocean, it doesn’t take very many sales to boost the new release in genre categories. Based on the workshop speaker, I’m a best-selling author because of that as well. I think my upcoming Trusting Uncertainty hit #50 in one sub genre, and hung on by its toenails in the 80s and 90s in two others.

Early on the day of the new release ad, I checked (because of course I did).

And look who else I’m sharing the stage with.

However, unlike Mr. Gilstrap, who has a much larger body of top-sellers, I can’t, with clear conscience, declare myself an author of best-selling books, or a best selling author. (I do, however use “award winning author” because I have won awards for my books.)

However, unlike Mr. Gilstrap, who has a much larger body of top-sellers, I can’t, with clear conscience, declare myself an author of best-selling books, or a best selling author. (I do, however use “award winning author” because I have won awards for my books.)

What’s your take, TKZers?

Now available for Preorder. Trusting Uncertainty, Book 10 in the Blackthorne, Inc. series.

Now available for Preorder. Trusting Uncertainty, Book 10 in the Blackthorne, Inc. series.

You can’t go back and fix the past. Moving on means moving forward.

Terry Odell is an award-winning author of Mystery and Romantic Suspense, although she prefers to think of them all as “Mysteries with Relationships.” Follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

Reader Friday: Writers as Readers

Last week’s answers got me thinking. Most everyone said they saw no reason to finish a book they weren’t enjoying, for a variety of reasons. Someone told me that once you’re a writer, you can never read the same way again.

Last week’s answers got me thinking. Most everyone said they saw no reason to finish a book they weren’t enjoying, for a variety of reasons. Someone told me that once you’re a writer, you can never read the same way again.

As a writer, do you think you’re more critical than before you took up the craft? Did you finish more “unfinishable” books when you were “only” a reader? Has your definition of a “unfinishable” book changed?

Image by congerdesign from Pixabay

Are you a member of the clean plate club when it comes to reading? Or do you leave books unfinished? How much time do you give an author to convince you to keep reading? What makes you stop?

Note: I was once given the formula 100 minus your age = how many pages you “owe” an author.

When the Right Word is Wrong

Terry Odell

As writers, we deal in words. Thousands of words. And we’re always looking for the right word to use. But what happens when the right word is wrong?

As writers, we deal in words. Thousands of words. And we’re always looking for the right word to use. But what happens when the right word is wrong?

For example, I was reading a draft chapter from one of my writing pals. She’d written something about a man pulling up the collar of his t-shirt to wipe sweat off his face. My comment to her was, “T-shirts don’t have collars.” Her reply was “Yes, that’s what I was taught when I took sewing classes.” I recalled that when I worked a temp job, our jackets were provided, but we were told to wear shirts with collars, and the accepted attire was either a blouse with a collar or a polo shirt, but absolutely no t-shirts. Being curious, I hit the search engines and looked up t-shirts.

Merriam-Webster said this: a collarless short-sleeved or sleeveless usually cotton undershirt; also : an outer shirt of similar design

Wikipedia had this to say: a style of unisex fabric shirt, named after the T shape of the body and sleeves. It is normally associated with short sleeves, a round neckline, known as a crew neck, with no collar.

So, I was “right”—to a degree. Will readers stop reading to research words, especially ones they assume they know the meaning of? Not likely (as authors, we hate to pull anyone out of the read). However, some readers won’t notice it, because they consider the neckline of a t-shirt a collar. Others might hiccup, thinking the same way I did. Will it spoil the read? No.

Is there a solution? Maybe. When in doubt, I’d go with the dictionary definition. That way, if someone is puzzled enough to wonder, when they look it up, they’ll see the author was right.

Another example. My Triple-D Ranch series includes a character who runs a cooking school. I was writing a scene where she was teaching her students about the various pots and pans they’d be using. She was talking about the differences between frying pans and sauté pans (based on my trip through the Google Machine). I ran my draft by my (former) chef brother to see if I got things right. He came back and told me all my research was “wrong” because anyone trained in cooking wouldn’t use those terms, and proceeded (at some length) to set me straight. And therein lies the rub. He’s not my “target” reader, but he knows of what he speaks. Other readers might, too. And just as many would “know” that they’re right about the differences between sauté pans and frying pans. Either way, I’m right for some, and I’m wrong for some.

Another example. My Triple-D Ranch series includes a character who runs a cooking school. I was writing a scene where she was teaching her students about the various pots and pans they’d be using. She was talking about the differences between frying pans and sauté pans (based on my trip through the Google Machine). I ran my draft by my (former) chef brother to see if I got things right. He came back and told me all my research was “wrong” because anyone trained in cooking wouldn’t use those terms, and proceeded (at some length) to set me straight. And therein lies the rub. He’s not my “target” reader, but he knows of what he speaks. Other readers might, too. And just as many would “know” that they’re right about the differences between sauté pans and frying pans. Either way, I’m right for some, and I’m wrong for some.

What did I end up writing? My instructor now says,

“Most cooking techniques and terminology we use comes from the French. However, a lot of names have been Americanized, and none of you will be ready for a fancy French restaurant simply by completing this course. You’ll be cooks, not chefs. So, I’m not going to dwell on terminology too much. As long as you can match the right tool with the right task, you’ll do fine.”

And then there’s the most important part about choosing the right word. POV.

And then there’s the most important part about choosing the right word. POV.

Example 1

My characters were in a café, and it was one where customers place their orders at the counter, and the clerk hands them a metal stand with their order number on it to display on their table so the servers can find them.

First, I’d shown the heroine entering the café and placing her order.

She paid for her meal, accepted the metal holder with the number eighteen from the clerk, and found a small table in the back of the crowded café, inhaling the blend of aromas as she waited for her order to be ready.

In the next scene, the hero arrives and places his order.

At the counter, Bailey ordered a burger—a man had to eat, right?—and carried his stand with its number to Tyrone’s table.

My critique partner had trouble with the word “stand” in the second example, and asked what they were really called, and maybe I should use that definition instead.

So, I took a quick trip through Google and learned they’re called “Table Number Stands,” so my use of the term is correct.

Example 2

My character was at an event in a hotel, and she was going to leave, so she wanted to get rid of the half-empty glass she was carrying.

I’ve been to enough events at hotels or banquet halls, and I know the catering people normally have trays on stands set up at various places around the room where guests can deposit their used dishes. But I didn’t know what they were called.

But you know what? I forgot one crucial aspect. Would the character know?

What if my research showed the aforementioned table number stands were called Grabbendernummers. Then, I could have written, “Bailey carried his Grabbendernummer to the table.” But would he know that?

You see, it doesn’t really matter what you, the author knows or doesn’t know about something. It’s what the character knows. If my character with the half-empty glass were in the catering business, then yes, she’d refer to that tray by a proper name, if it had one. (And per my brother the chef and all the Googling I’d done, there isn’t a specific term for them.) So, my heroine, would simply see the tray on a stand. It might be black, or brown, or covered with linens, but she’s going to think of it as a tray.

Yes, do your research. But if you want to save a lot of time—especially if you’re easily sidetracked while looking something up—ask yourself if the character would know whatever you’re researching first. Just because the author knows (or looked up) what a particular object is called, in Deep POV, it’s the character who has to know it. The character is going to use whatever vocabulary exists in his head, not the author’s.

Are you a stickler for the correct word? Do your characters know them?

Now available for Preorder. Trusting Uncertainty, Book 10 in the Blackthorne, Inc. series.

Now available for Preorder. Trusting Uncertainty, Book 10 in the Blackthorne, Inc. series.

You can’t go back and fix the past. Moving on means moving forward.

Terry Odell is an award-winning author of Mystery and Romantic Suspense, although she prefers to think of them all as “Mysteries with Relationships.” Follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

Tips for Dealing With Character Names

Terry Odell

Last week, John Gilstrap addressed coming up with character names, and there were a lot of helpful suggestions in the comments.

Last week, John Gilstrap addressed coming up with character names, and there were a lot of helpful suggestions in the comments.

I tend to hit the Google Machine. “Male (or female) Names Starting with …” is a frequent search. Another thing to add to that search is the year/decade that character was born. Name trends change with time.

I had a shocking realization when seeking a name for a character in a recent book.

Names have to “match” the characters to some extent. For me, it’s a loose match. Our country is so much of a melting pot that names often don’t match one’s ethnicity, and it’s often a stereotype to try to give them “appropriate” names. I recall my daughter, when she was in middle school, asking if her friend Kiesha could come visit. What’s your first visual? Probably not the blue-eyed blonde who showed up. But if I want an ethnic name, I just add that to my Google search.

This week, I thought I’d expand on John’s topic, because coming up with names is only part of the problem. You’ve cleared the choosing names for your characters hurdle. But there are pitfalls to avoid so you don’t confuse your readers.

A tip I picked up at a workshop was the reminder that the characters should sound like their parents named them, not you.

Major warning: Names shouldn’t be too similar to other characters in the book.

This mean no Jane and Jake, or Mick and Mack, or Michael and Michelle—and that includes nicknames. If everyone calls Michael Mike, and there’s another character named Norman, but Norman’s last name is MacDonald and everyone calls him Mac, then you’re setting things up for reader confusion. I recently read a book where the author had fixated on the letter B for character names, and these were major players, not bit parts. I don’t think I ever got them straight.

Many readers see the first few letters of a character’s name and connect it to whatever image they’ve created for that character. Your character might be named Anastasia, but the reader might be thinking “The blonde woman with the A name.”

So, how do you keep track so you don’t confuse or frustrate your readers? Here’s my system.

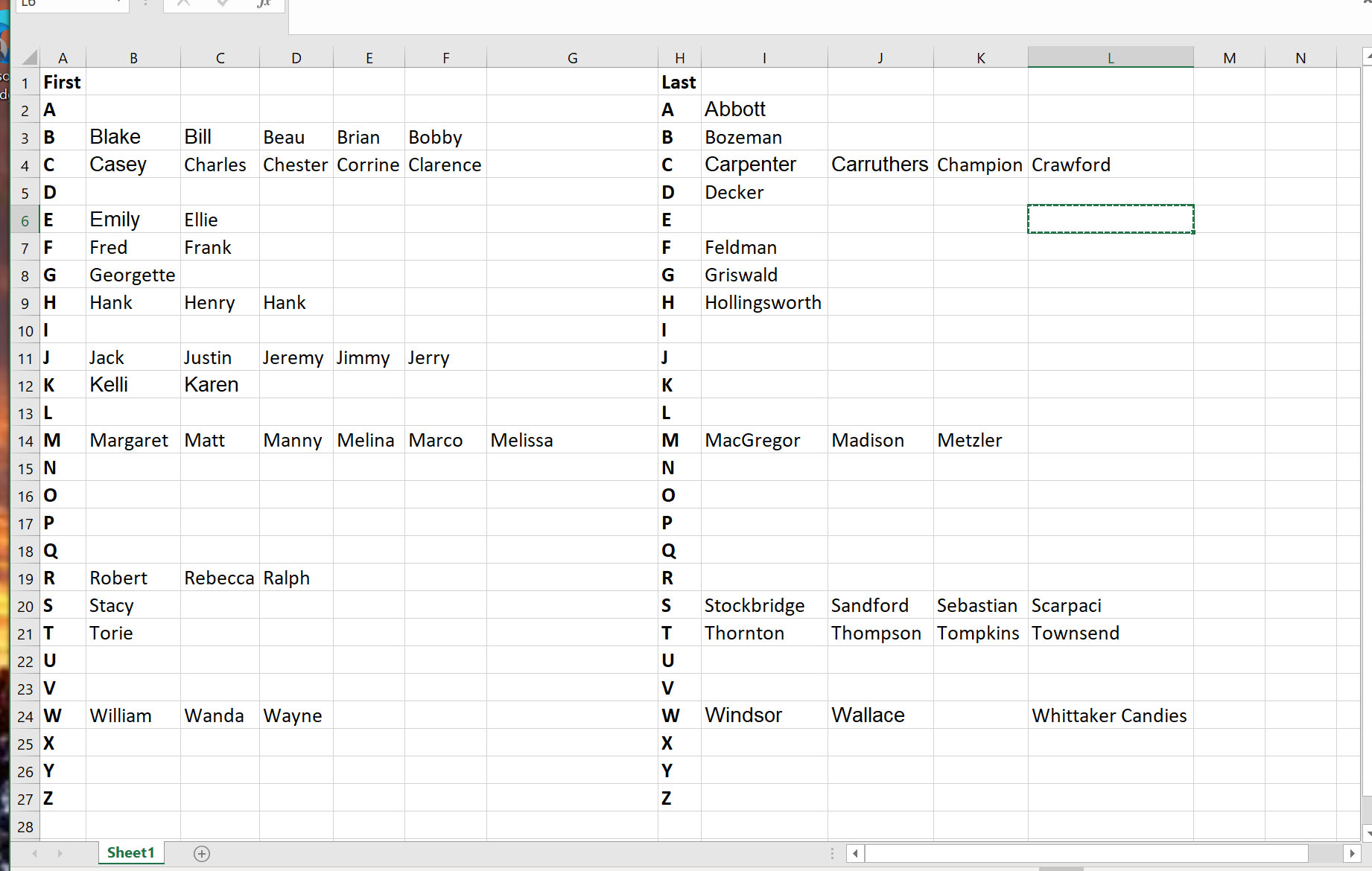

The late Jeremiah Healy prefaced one of his workshops with a very vocal complaint about character names in books. He said, “How hard is it to take a sheet of paper, write the alphabet in two columns, and then put first names in one, last names in the other?”

Now that we’re using computers, instead of a sheet of paper, I use a simple Excel spreadsheet. When I name a character, I fill in a blank field in the appropriate line. This lets me see at a glance when I start to fixate on a letter. I hadn’t been to Healy’s workshop when I wrote What’s in a Name? but when rights reverted to me, I used the spreadsheet and was shocked at what I’d discovered. THREE characters named Hank? Okay, only two, but the third was Henry “but you can call me Hank.” I still haven’t forgiven my then editor for that one.

This is what I found when I went through the book:

(You can click to enlarge the images)

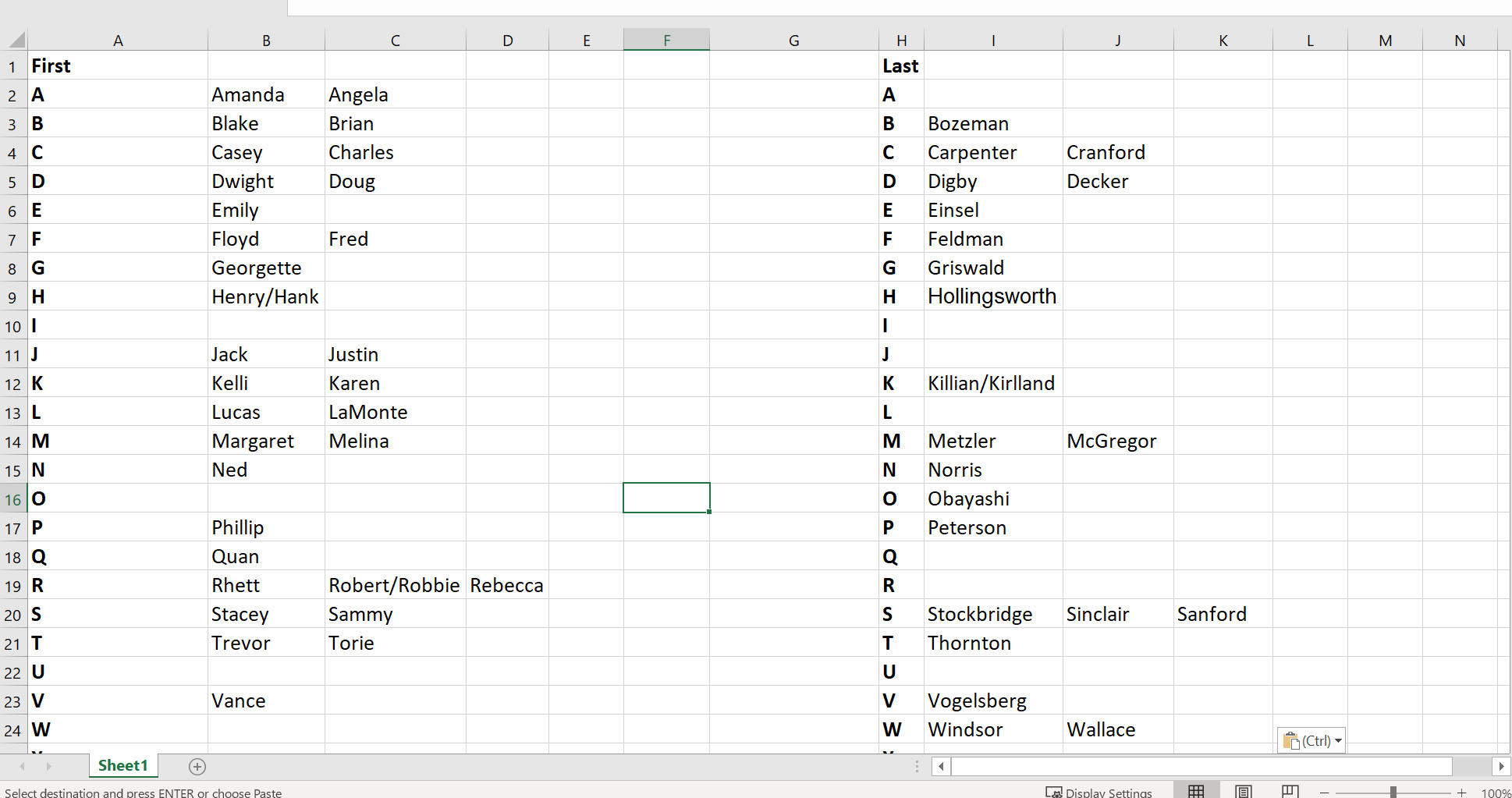

In addition to making minor revisions to the text, you can be sure I updated the character names. Here’s the “after” spreadsheet.

In addition to making minor revisions to the text, you can be sure I updated the character names. Here’s the “after” spreadsheet.

Other considerations. Foreign names might be realistic, but what if a reader is unfamiliar with the name, or its pronunciation? One of my critique partners wrote a book with a family of Irish descent, and she’s calling one of the characters Siobhan. (If I were naming a character that, the first thing I’d do would be to set up an auto correct, because I’d probably spell it wrong more often than not.) But typing it right is the author’s problem, not the reader’s. Do you know how to pronounce Siobhan? (shi-VAWN) If the author tells you, when you see the word do you “hear it” or is it strictly a visual?

Other considerations. Foreign names might be realistic, but what if a reader is unfamiliar with the name, or its pronunciation? One of my critique partners wrote a book with a family of Irish descent, and she’s calling one of the characters Siobhan. (If I were naming a character that, the first thing I’d do would be to set up an auto correct, because I’d probably spell it wrong more often than not.) But typing it right is the author’s problem, not the reader’s. Do you know how to pronounce Siobhan? (shi-VAWN) If the author tells you, when you see the word do you “hear it” or is it strictly a visual?

(With apologies to Brother Gilstrap, I never see/hear his character Venice as Ven-EE-chay, no matter that he’s made the pronunciation clear. To me, she’s “Not Venice” in my head.)

And then, there’s a whole new set of problems. Audiobooks. When I started to put my books into audio, I had to focus on what things sound like as well as look like. In my third Triple-D Ranch book, the heroine’s ex-husband’s name is Seth. Her sister’s name is Bethany. They don’t look very similar on the page, but when spoken, I’m concerned that they’ll sound too much alike, especially if they’re in the same sentence. Or even paragraph. I don’t want my narrator stumbling (or calling them both Sethany).

All right, TKZers. Share your tips for keeping track of character names.

Now available for Preorder. Trusting Uncertainty, Book 10 in the Blackthorne, Inc. series.

Now available for Preorder. Trusting Uncertainty, Book 10 in the Blackthorne, Inc. series.

You can’t go back and fix the past. Moving on means moving forward.

Terry Odell is an award-winning author of Mystery and Romantic Suspense, although she prefers to think of them all as “Mysteries with Relationships.” Follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

Character Descriptions – Part 2

Terry Odell

Last time, I gave some tips for character description. I’ll repeat them here:

Last time, I gave some tips for character description. I’ll repeat them here:

Today’s focus is on dealing with character descriptions in First Person or Deep/Close/Intimate Third (which are almost the same thing.)

I am a deep point of view person. I prefer everything to come from inside the character’s head, However, I will read—and enjoy—books written with a shallower point of view. It all comes down to the way the author handles things.

What are authors trying to convey to their readers with physical character descriptions? The obvious: hair color, length, style to some extent. Eye color. Height, weight, skin color. Moving forward, odds are the character is dressed, so there’s clothing to describe. This is all easier in a distant third POV. Using that POV, you can stop the story for a brief paragraph or two of description, a technique used by John Sandford. In a workshop, he said he didn’t like going into a lot of detail, and listed the basics that he conveys in each book, usually in a single paragraph. Here’s how he describes Lucas Davenport in Chapter 2 of Eyes of Prey, one of his early Davenport books:

Lucas wore a leather bomber jacket over a cashmere sweater, and khaki slacks and cowboy boots. His dark hair was uncombed and fell forward over a square, hard face, pale with the departing winter. The pallor almost hid the white scar that slashed across his eyebrow and cheek; it became visible only when he clenched his jaw. When he did, it puckered, a groove, whiter on white.

But what if you want to write in deep point of view? Staying inside the character’s head for descriptions is a challenge. Is the following realistic?

Sally rushed down the avenue, her green-and-yellow silk skirt swirling in the breeze, floral chiffon scarf trailing behind her. She adjusted her Oakley sunglasses over her emerald-green eyes. When she reached the door of the office building, she finger combed her short-cropped auburn hair. Her full, red lips curved upward in a smile.

You’ve covered most of the “I want my readers to see Sally” bases, but be honest. Do you really think of yourself in those terms?

There are other ways to convey that information. First, trust that your reader will be willing to wait for descriptions. Make sure there’s a reason for the character to think about her clothes, or her hair. Maybe she just had a total makeover and isn’t used to the feel of short hair, or the new color, or the makeup job. Catching a glimpse of herself as she passes a mirror and doing a double-take is one of the few times the “Mirror” description could work for me.

Even better, use another character. Some examples of how I’ve handled it:

Here, an ex-boyfriend has walked into Sarah’s shop and says to her:

“You look like you haven’t slept in a month. And your hair. Why did you cut it?”

“Well, thanks for making my morning.” Sarah fluffed her cropped do-it-yourself haircut. “It’s easier this way.”

Note: there’s no mention of the color. Someone else can bring it up later. Neither of these characters would be thinking of it in the context of the situation.

Later, Sarah is opening the door to Detective Detweiler. We’re still in her POV, but now we can see more about her as well as a description of the detective, and since it’s from her POV, there’s none of that ‘self-assessment’ going on.

She unlocked the door to a tall, lanky man dressed in black denim pants and a gray sweater, gripping several bulky plastic bags. At five-four, Sarah didn’t consider herself exceptionally short, but she had to tilt her head to meet his eyes.

Sometimes, there are compromises. My editor knows I don’t like stopping the story, especially at the beginning to describe characters, but she knows readers might want at least a hint.

This was the original opening paragraph I sent to my editor:

Cecily Cooper’s heart pounded as she stood in the judge’s chambers, awaiting the appearance of Grady Fenton, the first subject in her pilot program, Helping Through Horses. She’d spent months working out the details, hustling endorsements, groveling for grant monies, and had done everything in her power to convince her brother, Derek, to give Grady a job at Derek’s Triple-D Ranch.

This was my editor’s comment to that opening: Can you add a personal physical tag for Cecily somewhere on the first page—hair, what she’s wearing? There’s a lot of detail that comes later, but there should be something here to help the reader connect with her right away.

So, I figured there’s a good reason I’m paying her, and added a bit more.

Shuffling footfalls announced Grady’s arrival. Cecily ran her damp palms along her denim skirt, wishing she could have worn jeans so she’d have pockets to hide the way her hands trembled.

My reasoning: I mentioned the skirt was denim, because the fabric helps set the “cowboy” theme for the book, but there’s no more detail than that. Not how many buttons, or whether it’s got lace trim at the hem. Now, let’s say she was wearing Sally’s “girly” skirt. For Cecily, that would be far enough out of character for her to think about it, BUT, I’d make sure to show the reader her thoughts. Perhaps,

“She hated wearing this stupid yellow-and-green silk skirt—jeans were her thing—but Sabrina told her that skirt would impress the judge.”

See the difference between that and Sally’s self description earlier?

How do you handle describing your POV characters?

A brief moment of promotion–thanks to a BookBub Featured Deal, the box set of the first three novels in my Blackthorne, Inc. series is on special this week only for 99 cents instead of $6.99. Ends the 17th. Available at Kobo, Amazon, Apple & Nook.

A brief moment of promotion–thanks to a BookBub Featured Deal, the box set of the first three novels in my Blackthorne, Inc. series is on special this week only for 99 cents instead of $6.99. Ends the 17th. Available at Kobo, Amazon, Apple & Nook.

Terry Odell is an award-winning author of Mystery and Romantic Suspense, although she prefers to think of them all as “Mysteries with Relationships.” Follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

Character Descriptions, Part 1

Terry Odell

When I decided to address self-description, I found that it would make for a very long post. Since everyone’s time is valuable, I opted to split it into two posts, so you’ll get more on the topic when it’s my turn again. Today, it’s a few tips for writing character descriptions.

When I decided to address self-description, I found that it would make for a very long post. Since everyone’s time is valuable, I opted to split it into two posts, so you’ll get more on the topic when it’s my turn again. Today, it’s a few tips for writing character descriptions.

A while back, I started reading a book I’d received at a conference. I’d never heard of the author, and was looking forward to adding this one to my collection. I love discovering new authors and new characters, and since this book was part of a series, I knew, if I enjoyed it, there would be more.

I settled in to meet the characters. The first paragraph immediately punched some of my buttons. I prefer a “deep” or “close” point of view, and if the first time I meet a character, she’s brushing her thick auburn hair away from her face, I get antsy. People don’t normally think of themselves that way. This says, “outside narrator” to me. Not a deal-breaker, but not my taste. I’m a Deep POV person.

These descriptions went on with more self description—shoving white hands into the pockets of her black jeans. I don’t know about you, but I’ve never thought about what color my hands are—unless I’ve been painting.

I moved on to Chapter 2. My twitchiness increased when in the first paragraph, the introduction to the character had her capturing her long raven hair and fastening it into a ponytail. When the first sentence of chapter 3 introduced a new character pulling her long blond hair into a ponytail, I hit my limit.

Yes, understand that readers like to “see” characters, and if you’re not writing in a close POV, you can describe them the way an outside narrator would see them, but readers would like to see that you can get beyond hair—or at least vary more than the color. By now, I’m not seeing different characters, I’m seeing pages full of clones of faceless, shapeless, long-haired women with ponytails.

There’s more to describing a character than hair color. There are other physical features one can mention, as well as emotional states. Here are a couple of examples, all including hair and more.

From “An Unquiet Grave,” by PJ Parrish, where the protagonist is observing another character, one he knows from the past:

“She was standing at the stove, her hands clasped in front of her apron. She had put on a few more pounds, her face round and flushed from the heat of the oven. Her hairstyle was the same, a halo of light brown hair, a few curls sweat-plastered to her forehead.”

Another, this from “Rapture in Death” by JD Robb, who writes in an omniscient POV:

“The man was as bright as Roarke was dark. Long golden hair flowed over the shoulders of a snug blue jacket. The face was square and handsome with lips just slightly too thin, but the contrast of his dark brown eyes kept the observer from noticing.”

Or here, from “Rain Fall” by Barry Eisler, written in 1st person POV, where hair is a major part of the description of the main POV character, but it’s showing more than a simply physical description—and readers haven’t “seen” the POV character before this from page 7—we don’t need to know what he looks like from page 1, paragraph 1.

“When I returned to Tokyo in the early eighties, my brown hair, a legacy from my mother, worked for me the way a fluorescent vest does for a hunter, and I had to dye it black to develop the anonymity that protects me now.”

When I’m writing, I prefer to use very broad strokes and wait until another character does the describing. My editor and I go back and forth about how much time I should spend describing my heroine in my opening paragraphs “because readers like it” versus “it’s not how people think of themselves.” I know we’ll see her through the hero’s eyes in chapter 2, just as we’ll see him through her eyes. So, in my first chapter, in paragraph 1, readers see her emotional state. The only description comes in the second paragraph:

Or (not to put myself in a league with the above quoted authors), a quick sample from one of my books. The character is on her way to a job interview.

“She refreshed her makeup, then finger-combed her hair, trying to get her curls to behave.”

Does it matter what color her hair is? She certainly knows and isn’t going to be thinking of it—unless she’s changed it for a reason, such as in the Eisler quote. We know she cares about grooming because she’s stopped to check her appearance before her interview. She wears makeup, which reveals something about her character, and she’s got unruly curls. That’s enough for page 1.

My tips:

Do you have any other tips to share? Pet peeves?

Terry Odell is an award-winning author of Mystery and Romantic Suspense, although she prefers to think of them all as “Mysteries with Relationships.” Follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

Are Gordon’s Days in Mapleton Numbered?

Deadly Options, a Mapleton Mystery/Pine Hills Police crossover.

Enough Already

Terry Odell

I talked about repetition in my last post. Today, another peeve along similar lines, triggered by the same author that bugged me enough to write that previous post. I understand (and agree) that sometimes telling is more efficient than showing. But how much? While I can understand an author’s desire to make sure the reader understands background, I’m not fond of his technique, which is to step in as the author and provide details that don’t seem worth stopping forward motion.

I talked about repetition in my last post. Today, another peeve along similar lines, triggered by the same author that bugged me enough to write that previous post. I understand (and agree) that sometimes telling is more efficient than showing. But how much? While I can understand an author’s desire to make sure the reader understands background, I’m not fond of his technique, which is to step in as the author and provide details that don’t seem worth stopping forward motion.

Michael Connelly feeds in background, but it never pulls me out of the story. This author, also writing a police procedural, isn’t pulling it off as well.

The two cops in the story—typical detective tropes: old, fat, donut eating guy just counting down to retirement, and the young, attractive female, recently promoted to detective—answer a call to a home where a neighbor says she saw blood. The cops take a look, and the newbie says, “Exigent circumstances?” Now, both cops know what this means, but the author decides to spend a paragraph explaining it. If the author wants to show the reader, why not have one of the cops explain it to the neighbor who wants to know why they’re not rushing right in?

Then there’s stopping the story for reflection. Two cops looking into a possible murder scene. Is this the time for one of them to reflect on what her siblings dressed up as on Halloween? And do we need to know the ages of those siblings? Is it important? Maybe. Is it important now? I don’t think so. Skimming right along.

Given the possible victims have connections to the movie industry, one of the witnesses mentions a possible suspect who’s a grip. She very nicely explains that a grip “moves lights and carries stuff on movie sets.”

That’s fine. Makes sense for her to explain it to the cops, but then the author takes us on another trip down memory lane while the rookie cop reflects on a family member who was also a grip, and how he was related, how often he visited, and what he brought them for Christmas. I’d call this a “stay in the phone booth with the gorilla” moment.

Details about what kind of magnets are holding up what kind of artwork on the fridge don’t move the story forward. The fact that there’s blood spatter on one of those pieces of art does.

In an attempt to give the readers information, the author has a scene between the rookie detective and the head of the Crime Scene Unit. It’s clear the author has researched the subject and wants to make sure readers know it, but how many readers care that the techs test stains they think are blood with tetramethylbenzidine? Just “We ran a test to confirm they’re blood” would probably work for 90% of readers. And do I want to know that they used HemDirect to tell if the blood was animal or human? Again, a simple “We determined the blood was human” would probably be sufficient. And this type of conversation went on and on for the entire chapter. We see the rookie detective using her knowledge, but her thoughts seem to be on the page as a way to explain—or over-explain—things for the reader. Or, worse, showcase the author’s research. Research should be like pepper. You don’t want to overwhelm the dish.

I’m also bothered by a lot of the roadmap descriptions. I don’t really care what street a sheriff’s station is on, or that the street runs alongside the southern edge of the 101 freeway. I’m direction-challenged, so telling me a hotel is seventy miles north of Los Angeles (even through I grew up there) doesn’t add anything. It makes me stop and try to imagine a map, thus pulling me out of the story. Unless you’re familiar with the city, seeing the turn-by-turn route a character takes won’t add anything to the story. Going into detail about how long it would take to get from point A to point B in varying traffic conditions, unless there’s a plot-related reason is just another speed bump. Even the Hubster, who has a much higher tolerance level for things that bother me, complained about the overdone roadmap scenes.

Where do you draw the line between description and info dumping? Genre matters, of course, but in commercial fiction, especially mysteries, thrillers, and action-adventure, too much might be as bad as too little.

Terry Odell is an award-winning author of Mystery and Romantic Suspense, although she prefers to think of them all as “Mysteries with Relationships.” Follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

Are Gordon’s Days in Mapleton Numbered?

Deadly Options, a Mapleton Mystery/Pine Hills Police crossover.