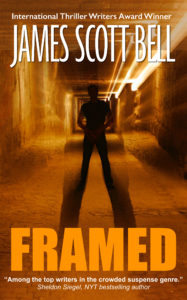

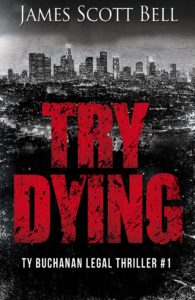

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

I got an email the other day from a young writer seeking advice about his foray into self-publishing. Here’s a clip:

As for my career this is going to be my debut work and as an author I currently have no  following. My goal with the book is to establish myself professionally and get a small following going as well as bring in a good amount of money for a first book. My question is what are some steps I can take to build publicity about the book and myself without having any real following or platform?

following. My goal with the book is to establish myself professionally and get a small following going as well as bring in a good amount of money for a first book. My question is what are some steps I can take to build publicity about the book and myself without having any real following or platform?

Here is my answer.

- A small following does not bring in “a good amount of money”

Of course, what qualifies as a “good amount” varies, but I’m assuming this writer means more than Starbucks money. To get there, you’ll need a large following and more than one book. When it comes to anything in the creative industry, if you are only focused on money, then you’re passion won’t shine through as much as you’d like to think. A lot of people can get caught up in this, especially just starting out. I know a few elderly people who were writers and did it becuase they loved it. After a while, they started publishing their stories and made a lot of money from it. A number of years after, they decided to retire. But because they had been writing for so long, they didn’t know where to begin on the retirement journey. So, they were advised to look into specialist companies like KeyAdvice for financial advice. I still speak to them sometimes and they tell me about all their stories about the holidays they have been on and how they are still writing. Not for profit, but just because they love it that much. Being an author can be rewarding. Everything will eventually fall into place for us creative individuals. We all need money to get by, but this shouldn’t just be your main focus.

So here’s what you should do to start off as an author…

- Attract a following with really good books

And what qualifies as a good book? Any book that follows all the advice on Kill Zone.

Ahem.

Only halfway kidding. It’s a book that is crafted in a way to connect with readers. It’s a book by an author serious about that craft. Which means …

- Get serious about your craft

Because this is what you want to do. But there’s a big difference between wanting to do something and actually doing it well. Get feedback from a critique group or beta readers or professional editors. And…

- Plan ahead

Even as you’re finishing your novel, be developing two or three or four more, because …

- Your first novel will probably not be ready for prime time

They say everybody has a novel inside them, and that’s usually the best place to keep it. Really. First novels are almost always best seen as a learning experience. Rarely does an author hit it out of the park on the first pitch. In the “old days” of traditional publishing (roughly 1450 – 2007) the vast majority of authors went through many rounds of rejection, and it was that third or fourth or fifth novel that finally sold.

There were some notable exceptions, like Brother Gilstrap’s debut effort, Nathan’s Run. An exception which, you guessed it, proves the rule.

Today, of course, you can easily self-publish, but that ease is a lure, because …

- Self-publishing is not a get-rich-quick scheme

The explosion of content out there now demands not only that books be of good quality, but that the author understand and implement some basic fundamentals about running a small business.

Self-publishing can be a profitable enterprise if you …

- Produce and market at a steady clip

The only real formula for making bank as an indie is quality production over time, sprinkled with a modicum of marketing knowledge. Keep in mind that the single greatest factor in selling books is word-of-mouth. Hands down. Glitzy marketing efforts only get you so far. Your books have to do the heavy lifting, so don’t fall into the trap of thinking the only thing that matters is how vigorously and breathlessly you check all the marketing boxes.

Keep writing and learning on parallel tracks, and …

- Don’t go shopping for a yacht

At least not until you can pay cash for it, and have enough in the bank for docking fees, upkeep and a crew. Which reminds me …

- Learn to handle money like a Scottish shopkeeper

That’s good advice for anybody, no matter what they do. But what you do is write, so follow the above advice and…

- Repeat over and over the rest of your life

A real writer writes and does not stop, even if it means managing only 250 words a day between family or work obligations. Even if it means you’ve got a broken leg and you’re in a cast that’s hanging on a chain from a rack over your hospital bed. You can still talk 250 words into Google Docs through your phone.

That is what you can expect from your first novel.

So, Zoners, what did you all learn by finishing your first novel? Where is it now?