by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

I’m currently working on a new thriller titled The Girl in the Window Who Saw the Woman on the Train Before She Was Gone. I don’t believe in chasing trends, unless it’s this one.

I’m currently working on a new thriller titled The Girl in the Window Who Saw the Woman on the Train Before She Was Gone. I don’t believe in chasing trends, unless it’s this one.

Actually, I wanted to talk about a sub-genre known as the “domestic thriller.” I’m not sure when this was coined, but it’s quite popular now, especially after Gillian Flynn’s runaway bestseller, Gone Girl. More recently, A. J. Finn’s The Woman in the Window has kept readers flipping the pages.

My research didn’t uncover a hard-and-fast definition of the domestic thriller. It seems to be a cousin of the psychological thriller, but with a home setting and (usually) a woman as protagonist and (usually) a male as the villain. A title like It’s Always The Husband (Michele Campbell) will clue you into the vibe.

I don’t, however, consider this a new genre. It’s at least as old as Gaslight, the 1938 play by Patrick Hamilton. You’ve probably seen the 1944 movie version for which Ingrid Bergman won the Academy Award as Best Actress. (I actually like the British version better. Released in 1940, it stars Anton Walbrook and the absolutely amazing Diana Wynyard. Catch it if you can!)

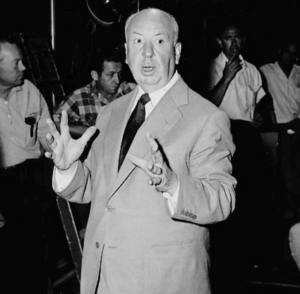

Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt (1943) may rightly be deemed a domestic thriller.

I would classify many of Harlan Coben’s books as domestic thrillers. Suburban setting, ordinary person, crazily extraordinary circumstances.

Which is my favorite kind of thriller. I’ve always loved Hitchcock, and he was the master at the ordinary man or woman theme. My favorite example is the 1956 version of The Man Who Knew Too Much starring James Stewart and Doris Day. The idea, Hitchcock once explained, came from a scene he pictured in his mind. A foreign, dark-skinned man, with a knife in his back, is being chased, and falls dead in front of some strangers. When someone tries to help him, heavy makeup comes off the man’s face leaving finger streaks on his cheeks.

So Hitchcock did that very thing. He had Stewart and Day as tourists in Morocco, and in the marketplace one morning a man with a knife in his back falls at Stewart’s feet. Stewart gets the face makeup on his hands.

Of course, right before he kicks the bucket the dying man whispers a secret of international importance into Jimmy’s ear, and we’re off and running. The bad guys want to know what Jimmy knows and they’re willing to kidnap his son to find out.

Another example: Cary Grant as the ad executive in North by Northwest (1959). Because of a terrible coincidence, he’s taken to be a master spy by two thugs who kidnap him outside of the Plaza Hotel. Cary is going to spend the next two hours on the run. His only consolation is that he gets to meet Eva Marie Saint.

One more, and this one is chilling because it was based on a true story. In Hitchcock’s The Wrong Man (1956), Henry Fonda, a happily married musician, resembles a gun-toting holdup man. He’s arrested and put through the wringer. Will the real culprit be nabbed before they lock the prison doors on Hank?

So why does the “ordinary man/woman” or the “domestic” thriller resonate so well? Perhaps because 1) it’s easy to empathize with the main character; and 2) it helps us deal with one of our darkest fears—having evil show up at our doorstep.

We read these kinds of thrillers, in part, to reaffirm our hope that there’s a moral force in the universe, that justice will prevail, and that we can get through anything if we hang on with courage.

Plus, we all like getting lost in the fictive dream of a page-turner. Escapist entertainment, Dean Koontz once said, is a noble enterprise, considering what we have to put up with on this spinning orb.

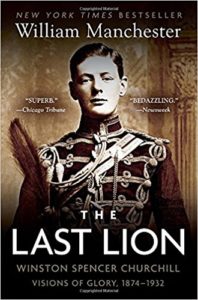

So in that spirit, I offer you my latest thriller, Your Son Is Alive.

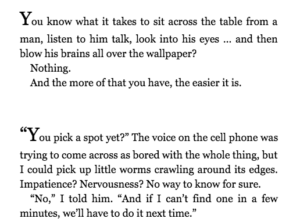

The idea for the book came from playing the first-line game. That’s where you just make up first lines that grab, not knowing anything else. One day I wrote this: “Your son is alive.”

Who says it? And why? And to whom?

I had to write the novel to find out.

So I did. The ebook is available from Amazon this week at the special launch price of $2.99:

(The print version will be available soon.)

As always, I have tried to write according to Hitchock’s Axiom: “Drama is life with the dull bits cut out.”

Do you have a favorite kind of thriller?