by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

I read a fascinating article the other day on how athletes’ bodies age. Using baseball players as an example, the author explains:

I read a fascinating article the other day on how athletes’ bodies age. Using baseball players as an example, the author explains:

[A]n athlete’s physical decline begins before most of us notice it, and even the 23-year-old body can do things today that it might not be able to do tomorrow. Fastball speed starts going down in a player’s early 20s, and spin rate drops with it. Exit velocity begins to decline at 23 or 24. An average runner slows a little more than 1 inch per second every year, beginning pretty much immediately upon his debut. It takes a little over four seconds for most runners to reach first base, which means with each birthday, it’s as if the bases were pulled 4 inches farther apart. Triples peak in a player’s early 20s, as does batting average on balls put into play. A 23-year-old in the majors is twice as likely to play center field as left field; by 33, the opposite is true.

Feeling tired yet?

Thirty-three feels so far away, but it’s already happening. The 23-year-old’s lean body mass peaked sometime in the preceding five years. His bone-mineral density too. He’s at the age when the body begins producing less testosterone and growth hormone. His body, knowing it won’t need to build any more bone, will produce less energy. Male fertility peaks in the early 20s, the same time as pitch speed and exit velocity. Athleticism is, crudely speaking, about showcasing what a body looks like when it’s ready to propagate a species.

Had kids yet?

And then there’s the brain:

Researchers in British Columbia studied decision-making speeds of thousands of StarCraft 2 players and found that cognitive abilities peak at 24. Other research has found that perceptual speed drops continuously after 25. The brain is changing: the ratios of N-acetylaspartate to choline, the integrity of myelin sheathing, the connectivity of hippocampal neurons — you know, baseball stuff.

So basically, after age 23 or so, we’re all on the treadmill to decline.

Thanks for stopping by TKZ, everyone!

Well, stats be hanged, I’m a Do not go gentle into that good night kind of guy. Might as well put up the good fight as long as you can with all the weapons available to you.

Especially if you’re a writer who wants to write until they find you with your cold, dead fingers poised over the keyboard.

Which means our brains—which house our imagination, tools of language, and craft knowledge—must be worked out just like a body.

I have long taught the discipline of a weekly creativity time, an hour (or more) dedicated to pure creation, mental play, wild imaginings. I like to get away from my office for this. I usually go to a local coffee house or a branch of the Los Angeles Library System. I also like to do this work in longhand. I mute my phone and play various games, like:

The First Line Game. Just come up with the most gripping first line you can, without knowing anything else about what might come after it.

The Dictionary Game. I have a pocket dictionary. I open it to a random page and pick a random noun. Then I write down what thoughts that noun triggers. (This is a good cure for scene block, too.)

Killer Scenes. I do this on index cards, and it’s usually connected to a story I’m developing. I just start writing random scene ideas, not knowing where they’ll go. Later I’ll shuffle the stack and take out two cards at a time, and see what ideas develop from their connection.

The What If Game. The old reliable. I’ll look at a newspaper (if I can find one) and riff off the various stories. What if that politician who was just indicted was really an alien from a distant planet? (Actually, this could explain a lot.)

Mind Mapping. I like to think about my story connections this way. I use a fresh blank page and start jotting.

After my creativity time I find that my brain feels more flexible. Less like a grouchy guy waiting on a bench for a bus and more like an Olympic gymnast doing his floor routine.

Now, I’m going to float you a theory. I haven’t investigated this. It’s just something I’ve noticed. It seems to me that the incidence of Alzheimer’s among certain groups is a lot lower than the general population. The two groups I’m thinking of are comedians and lawyers.

What got me noticing this was watching Carl Reiner and Mel Brooks being interviewed together, riffing off each other. Reiner was 92 at the time, and Brooks a sprightly 88. They were both sharp, fast, funny. Which made me think of George Burns, who was cracking people up right up until he died at 100. (When he was 90, Burns was asked by an interviewer what his doctor thought of his cigar and martini habit. Burns replied, “My doctor died.”)

So why should this be? Obviously because comedians are constantly “on.” They’re calling upon their synapses to look for funny connections, word play, and so on. Bob Hope, Groucho Marx (who was only slowed down by a stroke), and many others fit this profile.

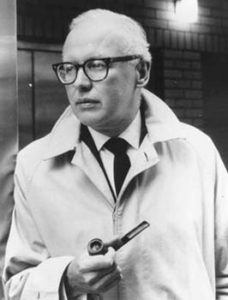

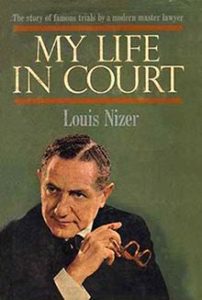

And I’ve known of several lawyers who were going to court in their 80s, still kicking the stuffing out of younger opponents. One of them was the legendary Louis Nizer, whom I got to watch try a case when he was 82. I knew about him because I’d read my dad’s copy of My Life in Court (which is better reading than many a legal thriller). Plus, Mr. Nizer had sent me a personal letter in response to one I sent him, asking him for advice on becoming a trial lawyer.

And I’ve known of several lawyers who were going to court in their 80s, still kicking the stuffing out of younger opponents. One of them was the legendary Louis Nizer, whom I got to watch try a case when he was 82. I knew about him because I’d read my dad’s copy of My Life in Court (which is better reading than many a legal thriller). Plus, Mr. Nizer had sent me a personal letter in response to one I sent him, asking him for advice on becoming a trial lawyer.

And there he was, coming to court each day with an assistant and boxes filled with exhibits and documents and other evidence. A trial lawyer has to keep a thousand things in mind—witness testimony, jury response, the Rules of Evidence (which have to be cited in a heartbeat when an objection is made), and so on. Might this explain the mental vitality of octogenarian barristers?

There also seems to be an oral component to my theory. Both comedians and trial lawyers have to be verbal and cogent on the spot. Maybe in addition to creativity time, you ought to get yourself into a good, substantive, face-to-face conversation on occasion. At the very least this will be the opposite of Twitter, which may be reason enough to do it.

So what about you? Do you employ any mental calisthenics?