by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

We’ve talked before about not settling for mere competence in your writing. We’ve already got plenty of that. The “tsunami of content” available for the consumer of fiction today is made up largely of a spectrum that ranges stink bomb to okay, with the scale tilted decidedly toward the former. It has ever been so, according to Sturgeon’s Law.

So if you want word-of-mouth, and delighted readers, you’ve got to bring something extra to the page. Today I want to talk about adding snap to your style.

As an example of how to do it, I turn us back to another tsunami, the boom in mass market paperback originals from the 1950s. The public, just beginning their addiction to television, was still voracious in its reading habits. Drugstore spinner racks had to be replenished daily with new titles from such publishers as Gold Medal and Pocket Books.

As a result, noir and crime and mysteries were cranked out by scores of writers, accompanied by racy covers and taglines such as: An isolated mountain lodge—and open season on SIN! and She had the face of a madonna and a heart made of dollar bills!

Most of this fiction was serviceable. It did its job and was soon forgotten. But within this market there emerged some fine, even great writers. The ones who stood out always gave their fiction something extra, usually in the style. John D. MacDonald was one. Another was Gil Brewer.

Brewer’s life was writing and writing was his life. Unfortunately, when he wasn’t writing he was drinking. Sadly, the bottle killed him. But before his decline he wrote some of the leanest, meanest noir on the market. You can read about Brewer in this tribute by Bill Pronzini, wherein he writes:

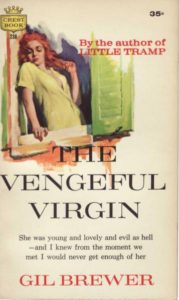

Despite some lurid titles – Hell’s Our Destination, And the Girl Screamed, Little Tramp, The Brat, The Vengeful Virgin– Brewer’s fifties GM [Gold Medal] and Crest novels are neither sleazy nor sensationalized; they are the same sort of realistic crime-adventure stories John D. MacDonald and Charles Williams were producing for GM, and of uniformly above-average quality. Most are set in the cities, small towns, waterways, swamps, and backwaters of Florida, Brewer’s adopted home. …The protagonists are ex-soldiers, ex-cops, drifters, convicts, blue-collar workers, charterboat captains, unorthodox private detectives, even a sculptor. The plots range from searches for stolen gold and sunken treasure to savage indictments of the effects of lust, greed, and murder to chilling psychological studies of disturbed personalities.

Hard Case Crime has re-published The Vengeful Virgin. I picked it up based on Brewer’s name. And as you can see from the original cover and marketing copy, it was one of those lust-and-greed-leads-to-murder tales. But it stands out from so many others because of the snap in Brewer’s style.

The book is about Jack Ruxton, who runs a TV sales and repair shop. He makes a housecall one day to the home of Victor Spondell, an old invalid who is being cared for by his eighteen-year-old stepdaughter, Shirley Angela.

It doesn’t take long for Jack and Shirley to fall in lust. Then try to figure out a way to murder Victor so Shirley can lay claim to the three-hundred grand he’s left to her.

The book is written in First Person POV. At one point, with the plan underway, Jack is alone in his store, feeling like a caged animal. He needs to get something to eat. A competent writer might have written the following paragraph:

After awhile it was time to eat something again, so I walked down to the drugstore and had a ham sandwich and a glass of milk. It was dark outside. There was some light from the street. Cars went up and down, maybe to parties and good times, or just home to TV and the evening paper.

That’s fine. It’s competent. But Brewer is more than that. He wrote it this way:

After awhile it was time to eat something again, so I walked down to the drugstore and fooled around with a ham sandwich and a glass of milk. It was dark outside. Neon glowed in the streets. Cars hissed up and down on their way to parties, maybe, good times, or just home to the one-eyed monster, and the evening paper.

That right there is the elusive thing called voice. It’s a symbiosis of writer and character rendered with craft on the page. Look at the verbs—fooled around, hissed. And the specific nouns—Neon, one-eyed monster. That’s how Jack Ruxton would talk, pressed through the gauze of a skilled writer’s imagination.

So our lesson today is simple:

- Know your character’s voice intimately

- Look for more descriptive verbs consistent with that voice

- Be specific with the nouns

Go ahead and use a thesaurus. I wrote this sentence: I ate a hamburger. Just for laughs, I opened my Mac dictionary, entered “eat” and went to the thesaurus. There I found: devour, ingest, partake of; gobble (up/down), bolt (down), wolf (down); swallow, chew, munch, chomp; informal guzzle, nosh, put away, chow down on, tuck into, demolish, dispose of, polish off, pig out on, scarf (down).

In about ten seconds I decided on: I demolished a hamburger.

The best time to do this, in my experience, is by looking over your previous day’s pages. That’s not the time for major changes in plot or character. Just use it to put some snap in your style. Readers will notice.

What is your approach to style? Do you think about it as you write? Is there an author you’d like to emulate (not copy)?