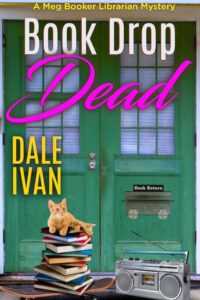

While writing Book Drop Dead it became obvious I wasn’t letting my subconscious have a much of say in the process. When I realized this and opened back up to my inner collaborator, the narrative became richer and more surprising and the writing flowed more easily. It’s a lesson I’ve taken to heart as I work on the next book in my mystery series.

Today’s Words of Wisdom takes a deep dive into the power of the subconscious in writing and how to set the scene for it to work its magic, with excerpts from posts by Laura Benedict, James Scott Bell and Debbie Burke.

There are so many theories on what dreams are. Just a few:

Subconscious problem solving.

Wishfulfillment

Random neuron firing

Emotional cleanup using dream symbols

Messages from the future or past

I don’t know about you, but my dreams tend to be a mix of the above, with the exception of messages from the future or past. As an adult, I’ve had some very comforting dreams about my grandparents, but I put those in the emotional cleanup category.

Dreams are as entertaining to me as a good book, and sometimes even more so because I’m participating. I go to sleep hoping the dreams are good. The only time I fear them is when I’m home alone overnight and have paralyzing night terrors about strangers in my bedroom. But most of my dreams contain vibrant colors, vivid situations and storylines, and people I don’t often see. I couldn’t enjoy them more if I made them up myself. Which, in a way, I suppose I do. It’s my subconscious at work—that part of the brain from which I suspect my best writing material comes.

But how to access that material in the waking world? As writers, we are essentially creating dreams for our readers. Stories that are like reality, but just that much better. Just that much less predictable, like any good dream.

Some ways to access the dreaming part of your brain:

Lucid dreaming: Lucid dreaming is dreaming when you know you’re dreaming. You won’t necessarily control your dreams, but you’re likely to remember them. Here’s a comprehensive list of ways to make it happen.

Dream journals: This is one of my favorites. As soon as I wake, I jot down the details of all the dreams I can remember. The exercise of writing it out makes me feel like I have a jump on my creative day.

Music: Do you listen to music as you write? It can quickly put you in the writing zone, but music with lyrics can be distracting. When I wrote Charlotte’s Story, I had this adagio on a loop for weeks. Repeated music is a great self-hypnosis tool.

Rituals: Same Bat Place. Same Bat Time. If you’re in the habit of doing deep work in the same place every time, your brain will begin to relax once it’s in sight.

Silence: I used to brag a lot about how I could write just as easily in a noisy cafe as I could in a silent room. While it’s still true, silence settles me much more quickly. You can almost hear the doors in my head opening.

Do you have trouble recalling your dreams? It’s common.The reason it’s sometimes difficult is because the brain may shut down its memory-recording functions while we’re in REM sleep.

Here’s what I find so fascinating about recalling dreams—or even having them. What if they really are simply random discharges of neurons firing up images in our brains while we sleep? That doesn’t make them any less interesting or less vital. It’s what we do with the connections between those images that makes a dream a dream. Even while we are sleeping, we are constructing narratives. How cool is that? Storytelling is so elemental to our being that we may be compelled to do it unintentionally, while we’re asleep.

That means that we are all storytellers. But to be writers, we have to externalize those narratives.

Laura Benedict—February 22, 2017

In an article in the Harvard Business Review, “Your Brain Can Only Take So Much Focus”, Dr. Srini Pillay writes about our over-emphasis on focus. We have our to-do lists, timetables, goals. And there’s nothing wrong with that. But it turns out we also should be practicing “unfocus.”

In keeping with recent research, both focus and unfocus are vital. The brain operates optimally when it toggles between focus and unfocus, allowing you to develop resilience, enhance creativity, and make better decisions too.

When you unfocus, you engage a brain circuit called the “default mode network.” Abbreviated as the DMN, we used to think of this circuit as the Do Mostly Nothing circuit because it only came on when you stopped focusing effortfully. Yet, when “at rest”, this circuit uses 20% of the body’s energy (compared to the comparatively small 5% that any effort will require).

The DMN needs this energy because it is doing anything but resting. Under the brain’s conscious radar, it activates old memories, goes back and forth between the past, present, and future, and recombines different ideas. Using this new and previously inaccessible data, you develop enhanced self-awareness and a sense of personal relevance. And you can imagine creative solutions or predict the future, thereby leading to better decision-making too. The DMN also helps you tune into other people’s thinking, thereby improving team understanding and cohesion.

Dr. Pillay recommends building “positive constructive daydreaming” (PCD) into your day. I do this very well at my local coffee house. I stare. Out the window. Sometimes at people. I’m really working, though. That’s PCD time!

Another tip from the good doctor: power naps. “When your brain is in a slump, your clarity and creativity are compromised. After a 10-minute nap, studies show that you become much clearer and more alert.”

But the technique that really jumped out at me was this:

Pretending to be someone else: When you’re stuck in a creative process, unfocus may also come to the rescue when you embody and live out an entirely different personality. In 2016, educational psychologists, Denis Dumas and Kevin Dunbar found that people who try to solve creative problems are more successful if they behave like an eccentric poet than a rigid librarian. Given a test in which they have to come up with as many uses as possible for any object (e.g. a brick) those who behave like eccentric poets have superior creative performance. This finding holds even if the same person takes on a different identity.

When in a creative deadlock, try this exercise of embodying a different identity. It will likely get you out of your own head, and allow you to think from another person’s perspective. I call this psychological halloweenism.

This is close to something I’ve done on occasion. I may have finished a draft and am doing the first read through. Something’s not working. I don’t know what.

I set it aside for awhile and do something unfocused: like pleasure reading, eating a Tommy Burger, or riding my bike. Then when I go back to it I think of a favorite author and pretend he’s looking over my shoulder at the draft. I have him say, “I think you need to ….” and just imagine what he would advise. It’s amazing how often this can break the logjam.

In light of all the science, then, I’ve determined to take a little more unfocus time on weekends.

I’ve also gotten more specific about how I spend my focus time. I’m a morning person. I like getting up while it’s still dark and pouring that first cup of java and getting some words down. I can write for two or three hours straight. But I’ve stopped doing that. I am forcing myself to take a break after 45 minutes of writing, to let the noggin rest a bit. Ten minutes maybe. Then back to work.

James Scott Bell—May 28, 2017

What is the subconscious? Novelist/writing instructor Dennis Foley reduces the definition to a simple, beautiful simile:

The subconscious is like a little seven-year-old girl who brings you gifts.

Unfortunately, our conscious mind is usually too busy to figure out the value of these odd thoughts and dismisses them as inconsequential, even nonsensical.

The risk is, if you ignore the little girl’s gifts, pretty soon she stops bringing them and you lose touch with a vital link to your writer’s imagination. But if you encourage her to bring more gifts, she’s happy to oblige.

Sometimes the little girl delivers the elusive perfect phrase you’ve been searching for or that exhilarating plot twist that turns your story on its head.

At those times, she’s often dubbed “the muse.”

The trick is how to consistently turn random thoughts into gifts from a muse. Here are eight tips:

#1 – Be patient and keep trying.

Training the subconscious to produce inspiration on demand is like housetraining a puppy.

At first, it pees at unpredictable times and places. You grab it and rush outside. When it does its business on the grass instead of expensive carpet, you offer lots of praise. Soon it learns there is a better time and place to let loose.

Keep reinforcing that lesson and your subconscious will scratch at the back door when it wants to get out.

#2 – Pay attention to daydreams, wild hare ideas, and jolts of intuition. Chances are your subconscious shot them out for a reason, even if that reason isn’t immediately obvious.

Say you’re struggling over how to write a surprise revelation in a scene. Two days ago, you remembered crazy Aunt Gretchen, whom you hadn’t thought about in years. Then you realize if a character like her walks into the scene, she’s the perfect vehicle to deliver the surprise.

#3 – Expect the subconscious to have lousy timing.

That brilliant flash of inspiration often hits at the most inconvenient moment. In the middle of a job interview. In the shower. Or while your toddler is having a meltdown at Winn-Dixie.

Finish the task at hand but ask your subconscious to send you a reminder later. As soon as possible, write down that brilliant flash before you forget it.

#4 – Keep requests small.

Some authors claim to have dreamed multi-book sagas covering five generations of characters. Lucky them. My subconscious doesn’t work that hard.

Start by asking it to solve little problems.

As you’re going to bed, think about a character you’re having trouble bringing to life. Miriam seems flat and hollow but, for some reason you can’t explain, she hates the mustache on her new lover, Jack. Ask your subconscious: “Why?”

When you wake up, you realize Jack’s mustache looks just like her uncle’s did…when he molested Miriam at age five.

Until that moment, you didn’t even know Miriam had survived abuse…but your subconscious knew. That’s why it dropped the hint about her dislike for the mustache. She becomes a deeper character with secrets and hidden motives you can use to complicate her relationship with Jack.

#5 – Recognize obscure clues.

This tip takes practice because suggestions from the subconscious are often oblique and challenging to interpret.

You want to write a scene where a detective questions a suspect to pin down his whereabouts at the time of a crime. You ponder that as you drift off to sleep. The next morning, “lemon chicken” comes to mind.

What the…?

But you start typing and pretty soon the scene flows out like this:

“Hey, Fred, you like Chinese food?”

“Sure, Detective.”

“Ever try Wang’s all-you-can-eat buffet?”

“That’s my favorite place. Their lemon chicken is to die for.”

“Yeah, it’s the best.”

[Fred relaxes] “But not when it gets soggy. I only like it when the coating is still crispy.”

“Right you are. I don’t like soggy either.”

“Detective, would you believe last night I waited forty-five minutes for the kitchen to bring out a fresh batch?”

“Wow, Fred, you’re a patient man. About what time was that?”

“Quarter to eight.”

“So you must have been there when that dude got killed out in the alley.”

[Fred fidgets and licks his lips] “Um, yeah, but I didn’t see anything. I had nothing to do with him getting stabbed.”

“Oh really? Funny thing is, nobody knows he got stabbed…except the killer.”

Lemon chicken directed you to an effective line of questioning to solve the crime.

Debbie Burke—February 5, 2019

***

- Have you tapped your dreams for you writing? If so, in what way?

- Do you give yourself a break and let your subconscious work it’s magic while you’re mentally elsewhere? Is there a particular activity, like talking a walk or a shower that helps in this?

- Do you listen to your inner “seven-year-old” and accept the gifts it has to offer your writing? Any tips on doing so?

***

There’s a sign above the library book drop: NO TRASH OR VIDEOTAPES. Meg never thought she’d have to add: NO DEAD BODIES.

It’s May 1985 and Meg Boo ker already has her hands full, what with running the busy Fir Grove branch library, helping her flaky actor brother with his latest onstage project, and caring for an orphaned kitten that shows up outside the branch.

ker already has her hands full, what with running the busy Fir Grove branch library, helping her flaky actor brother with his latest onstage project, and caring for an orphaned kitten that shows up outside the branch.

Then a rare bank note goes missing at a library event, igniting a feud between two local collectors, and Meg thinks her life couldn’t get any more complicated… until a dead body turns up in the book drop room.

Racing against time, Meg must use all of her librarian skills to discover the real killer’s identity, before the police arrest her for the crime.

Book Drop Dead is the second title in the 1980s Meg Booker Librarian Mysteries series. It’s available at the major ebook retailers via this universal book link.

Private pilot Cassie Deakin lands in the middle of a nightmare when she finds her beloved Uncle Charlie has been assaulted by thieves. Then things get worse.

Private pilot Cassie Deakin lands in the middle of a nightmare when she finds her beloved Uncle Charlie has been assaulted by thieves. Then things get worse.