“Happiness consists of getting enough sleep. Just that, nothing more.” –Robert A. Heinlein, Starship Troopers

* * *

Koala bears are the experts when it comes to sleep. An adult koala averages about twenty hours of sleep each day! To those of us who are trying to pack as much writing, marketing, networking, and everything else into a 24-hour time period, that seems a little excessive..

So why do those cute, furry critters need so much sleep? Koalas exist primarily on a diet of toxic eucalyptus leaves, and it takes a lot of energy for their digestive systems to break down the leaves which turn out to be low in nutrients to begin with. Bottom line: koala bears get the amount of sleep they need to support their lifestyle.

So how does that apply to humans?

* * *

“A good laugh and a long sleep are the best cures in the doctor’s book.” –Irish Proverb

We all know that a good night’s sleep is essential for good health. Good sleeping habits help us maintain a healthy weight, lower stress levels, repair body tissue, and give us an overall sense of well-being. According to sleepfoundation.org, sleep is also conducive to mental acuity.

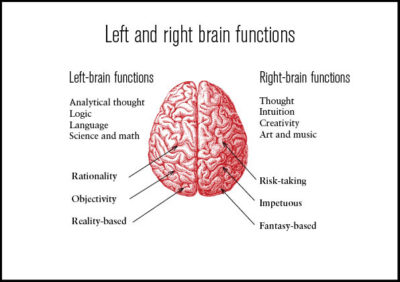

Sleep is believed to help with memory and cognitive thinking. Brain plasticity theory, a major theory on why humans sleep, posits that sleep is necessary so the brain can grow, reorganize, restructure, and make new neural connections. These connections in the brain help individuals learn new information and form memories during sleep. In other words, a good night’s sleep can lead to better problem-solving and decision-making skills.

Better sleep means better thinking, but how about creativity?

* * *

“Man is a genius when he is dreaming.” –Akira Kurosawa, Japanese Film Director

It turns out creativity and sleep are related.

Scientists generally divide sleep into two categories: Non-rapid eye movement (Non-REM) sleep and Rapid Eye Movement (REM) sleep.

Ideatovalue.com posted an article that compared the two categories and examined their effects on creativity.

-

Non-REM sleep is where information we engaged with during the day is processed and formed into memories

-

REM sleep is where those new memories are compared and integrated into all of the previous knowledge and memories we have. This is also usually when we dream. This may form new novel associations between distant pieces of information, a vital component for new ideas

The article concludes:

This would imply that REM sleep is important for not only our ability to associate new ideas and solve existing problems, but also form new original and divergently creative ideas.

Okay. We need a good night’s sleep to perform at our best, but how do we get it?

* * *

“A well-spent day brings happy sleep.” –Leonardo da Vinci

How much sleep do we need to maximize creativity? The National institutes of Health recommends adults get seven to nine hours of sleep a night. And how can you ensure a good night’s sleep? The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend

-

Be consistent. Go to bed at the same time each night and get up at the same time each morning, including on the weekends

-

Make sure your bedroom is quiet, dark, relaxing, and at a comfortable temperature

-

Remove electronic devices, such as TVs, computers, and smart phones, from the bedroom

-

Avoid large meals, caffeine, and alcohol before bedtime

-

Get some exercise. Being physically active during the day can help you fall asleep more easily at night.

* * *

So TKZers: Have you noticed a connection between sleep and creativity? How much sleep do you get each night? Do you remember your dreams and use them in your stories? Have you recovered from losing an hour of sleep to Daylight Savings Time?

* * *

Private pilot Cassie Deakin lands in the middle of a nightmare when she finds her beloved Uncle Charlie has been assaulted by thieves. Then things get worse.

Private pilot Cassie Deakin lands in the middle of a nightmare when she finds her beloved Uncle Charlie has been assaulted by thieves. Then things get worse.

Buy on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Kobo, Google Play, or Apple Books.

Most of us are able to recall one or two of our dreams, but what if there were ways to increase that number?

Most of us are able to recall one or two of our dreams, but what if there were ways to increase that number?![By Polygon data were generated by Database Center for Life Science(DBCLS)[2]. - Polygon data are from BodyParts3D[1], CC BY-SA 2.1 jp, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9621805](https://killzoneblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Superior_temporal_gyrus_animation.gif)

Brain cells in the left hemisphere have short dendroids which pull in information.

Brain cells in the left hemisphere have short dendroids which pull in information.