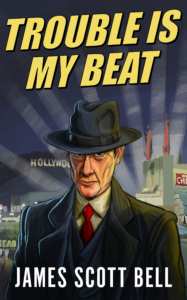

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

“Once upon a time,” I told my two oldest grandboys, “there were two baby monsters. One was green and one was blue. They lived in a cave with their mom and dad…”

“Once upon a time,” I told my two oldest grandboys, “there were two baby monsters. One was green and one was blue. They lived in a cave with their mom and dad…”

I had no idea what I would say next (Papa was pantsing and the pressure was on). Their eyes were riveted on me, with that expression children get when they are not really looking at you but at the pictures forming in their imaginations. There is nothing so precious as that look, and it was my task to keep it there.

Trouble being the key to plot, I got those baby monsters out of the cave and lost in the city (notice the urban landscape. I have too much noir in my bones to go bucolic). The trouble kept increasing—a truck almost hit them! A robber almost shot them! A building fell down around them!—until, finally, a stout-hearted policeman helped them get back home.

The boys were enraptured to the end. Then came my reward: “Tell us another story, Papa.”

Ah, the pure joy of making stuff up.

We’ve had several discussions over the years here at TKZ about why we write. Is it for love or money or a combo of both? (See, e.g., Debbie’s post on this topic and the comments thereto). Today I’d like to focus on another reason: pure, unadulterated joy.

Those of us who’ve labored inside the walls of the Forbidden City, where deadlines loom like nimbus clouds, know it’s not always fun and games. The beast of profit must be fed and the wolf of canceled contracts howls outside the gates.

For indies, there is business to attend to, with its expansive list of non-writing tasks. The demand to be prolific can dilute the simple joy of making stuff up.

Wherever you are in your writing, it’s crucial to find ways to nurture that joy. Getting into “the zone” when we work on our WIP is one way, though it’s hard to systematize. Some days the writing pours out of you; other days it’s like slogging through the La Brea Tar Pits in snowshoes. When I’m in the pits I find that doing some character work is the ticket back into “flow.” I’ll stop and do some thinking about one or two of the characters, and it doesn’t matter who they are—main, secondary, or a new one I make up. A bit more backstory, a secret held, a relationship hitherto unnoticed—in a little while I’m excited to dive back in.

That’s for my main work, full-length fiction. But I also take time for flash fiction, short stories, novelettes, and (as Steve mentioned yesterday) novellas. These I do these purely for fun. I don’t think about markets or editors or critics. It’s just me and my writing and new story worlds.

The nice thing is that even if a shorter work stalls out (it rarely does, for there is almost always a way to make things work) the exercise itself is good for my craft as a whole. It keeps me sharp and in shape. I write short fiction the way Rocky Marciano used the heavy bag. No one was ever in better shape than Marciano, which is why he was the only undefeated heavyweight champion in history.

I’ve quoted this before, but it bears repeating here:

In the great story-tellers, there is a sort of self-enjoyment in the exercise of the sense of narrative; and this, by sheer contagion, communicates enjoyment to the reader. Perhaps it may be called (by analogy with the familiar phrase, “the joy of living”) the joy of telling tales. The joy of telling tales which shines through Treasure Island is perhaps the main reason for the continued popularity of the story. The author is having such a good time in telling his tale that he gives us necessarily a good time in reading it. — Clayton Meeker Hamilton, A Manual of the Art of Fiction (1919)

I certainly had a good time writing a series of six novelettes about a Hollywood studio troubleshooter in the 1940s. These were originally written for my Patreon group, but the response was so positive I decided to put them all together in a collection which, coincidentally (how could I have known?) releases today!

TROUBLE IS MY BEAT is out now at the deal price of $2.99 (it goes up to $4.99 at the end of the week). For readers outside the U.S., go to your Amazon store and search for: B09V1RLXDM

Which brings up the joy of sharing your work. You can do that now in many ways. And if you’ve had fun in the writing, there’s a good chance you’ll have the fun of making new readers. You may even get a message along the lines of, “I just discovered your books! I love them! Keep writing, please!”

Why, that’s almost as good as, “Tell us another story, Papa.”

And that’s how I see the joy of making stuff up. How about you? Do you experience this often yourself? Does it come and go? How do you get it back when it takes a powder?

There’s a disturbing new trend on social media that could bankrupt authors. I first learned about it on Facebook, but it’s since traveled throughout all social media.

There’s a disturbing new trend on social media that could bankrupt authors. I first learned about it on Facebook, but it’s since traveled throughout all social media. Half my life’s in books, written pages.

Half my life’s in books, written pages.