The man who won’t read good books has no advantage over the man who can’t read them. — Mark Twain

By PJ Parrish

Saw a depressing video on Facebook the other day. People on the street were being polled about what was the last book they read.

The guy then asks folks to name an author. Any author. Crickets. Sigh.

I know we here at TKZ are preaching to the choir. But I also think maybe we need to be more worried about this. I’m not going to talk politics here, rest assured, but I am going to say that our ability to absorb information seems to be questionable, at best, these days. And we need to be smart right now. About a lot of things.

We need to read.

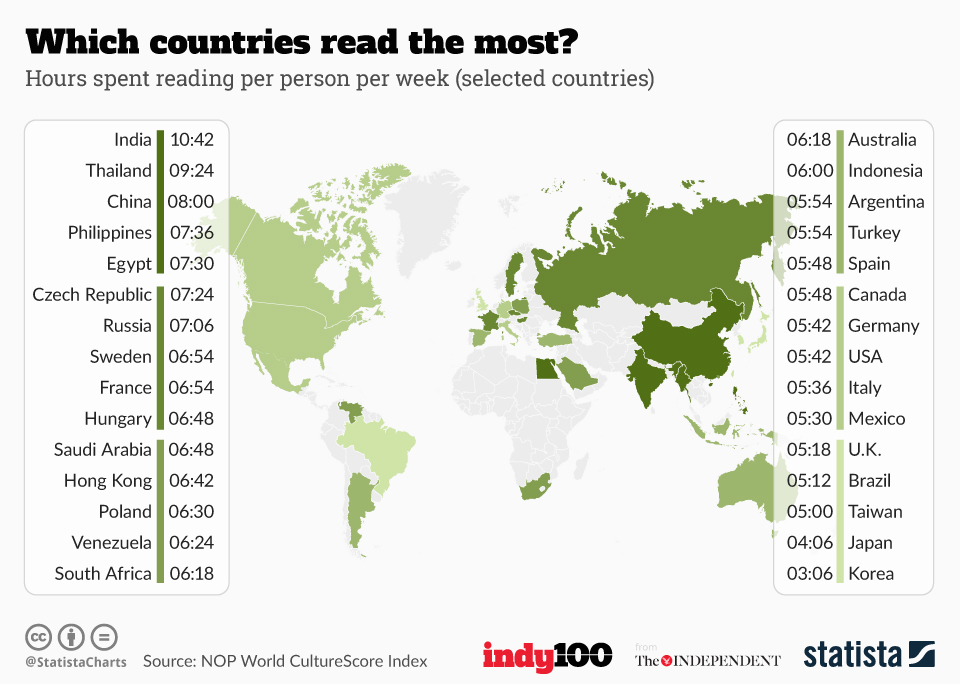

The latest Pew poll I could find on this subject says that 28% of adults ages 50 and older have not read a book in the past year, compared with 20% of adults under 50. . And as a country, we’re at the bottom of the reading pack.

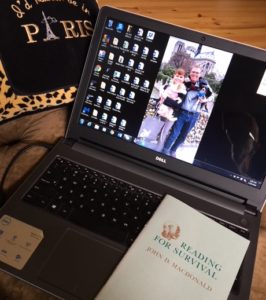

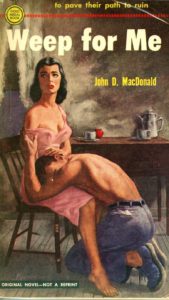

This subject slid to the front of my brain only because I was cleaning out my file drawer in my office. I found a slender little booklet that I had thought I had lost years ago. It’s a copy of an essay that John D. MacDonald wrote for the American Library Association and the National Endowment for the Arts.

It’s called Reading For Survival.

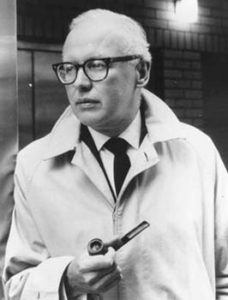

Now, if you think it’s some dust-dry diatribe, some shrill screed about how we’re raising a generation of morons, well, then you must not have read John D before. It reads like, well, one of his novels. (By the way, I didn’t know James and I would be writing about JDM in the same week. Click here to go back and read his post on what JDM taught him.)

A little background: Years ago, a friend of mine, Jean Trebbi, had a local TV show in South Florida called Library Edition. Jean was a force in the literary community. She was the head of the Broward County Center for the Book, a tireless supporter of all authors and most any book. In 1985, she interviewed MacDonald on her program, and when the camera stopped rolling, he kept going, but wanting to talk about non-readers instead of his own books.

Jean suggested he should write something on the subject for NEA and the Library Association. MacDonald didn’t want to do it, fearing he would be just preaching to the converted, but he finally agreed — with the caveat that he could use “colorful enough language to it will be quoted, sooner or later, to a great many non-readers.”

Things didn’t go well. “I could not make the essay work and I could not imagine why,” he recalls in the booklet’s forward. “I must have done two hundred pages of junk.”

Does hearing that make you feel any better about your own writing problems?

Jean Trebbi, finally wrote him asking what he hold-up was and MacDonald told her he had written a hot mess. Jean suggested using the device of a conversation between Travis McGee and and his friend Meyer. And that is what he did.

MacDonald called it “a small, mangy, bad-tempered mouse of 7200 words.” But as I re-read it the other day, I realized its message is as vital today than it must have been thirty-one years ago. MacDonald said the theme of his essay was “the terrible isolation of the non-reader, his life without meaning because he cannot comprehend the world in which he lives.”

If that doesn’t set off in a bell in your head, you haven’t been paying attention to what’s going on in our country these days.

The essay opens like a vintage MacDonald novel. Thunderclouds are gathering over the slips at Bahia Mar and McGee and Meyer are sitting on the deck of the Busted Flush. And next time someone tells you never open with weather, read them this:

The big thunder-engine of early summer was moving into sync along Florida’s east coast, sloshing millions of tons of water onto the baked land and running off too quickly as it always does.

An impressive line of anvil clouds marched ashore on that Friday afternoon in June, electrocuting golfers, setting off burglar alarms, knocking out phone and power lines, scaring the whey out of the newcomers.

The power goes out and Meyer puts down his book, and McGee says that it’s too dark to read anyway. (weather as metaphor!)

“I wasn’t reading, Travis,” Meyer said. “I was thinking about something. A passage in the book started me thinking about something.”

Over the next twenty-two pages, Meyer — whose mind is like a maze — spools out his argument — that man’s brain evolved the way it did, creating a genetic storehouse of memories, out of the pure need to understand his environment and thus survive.

Meyer concocts a prehistoric man named Mog and his modern counterpart Smith. Mog happens upon some fruit but he’s wary of eating it. Using all his memory skills, he decides to not chance it, that it’s a trap. His modern counterpart, Smith, gets a job offer at twice his salary. But using his memory skills, he deduces the employer is in a high risk banking arena with bad management turnover rates. So he says no.

“Back in prehistory,” McGee offers, “man learned and remembered everything he had to know about survival in his world. Then he invented so many tricks and tools, he had to invent writing. More stuff got written down than any man could possibly remember. Or use. Books are artificial memory. And it’s there when you want it. But for just surviving, you don’t need the books. Not any more.”

Books are artificial memory. Don’t you love that? But then Meyer lays it on him:

“So why are we doing such a poor job of surviving as a species, Travis?”

MacDonald goes on to say that the world of prehistoric man was small, limited to what the man could see, hear, taste, eat, kill, carry and use. But to modern man, who can read and remember, the world is huge and monstrously complicated.

“The man who can read and ponder big realities is a man keyed to survival of the species. He doesn’t have to read everything. That’s an asinine concept. He should have access to everything, but have enough education to differentiate between slanted tracts and balanced studies, between hysterical preachings and carefully researched data.”

Makes you wonder what MacDonald would have thought of today’s fake news debate, Facebook’s propaganda problems and the isolated little echo chambers we’ve crawled into. MacDonald and McGee go on:

“To be aware of the world you live in you must be aware of the constant change wrought by science, and the price we pay for every advance. These are our realities, and, like our ancestors of fifty thousand years ago, if we — as a species rather than an individual — are uniformed, or careless, or indifferent to the facts, then survival as a species is in serious doubt.”

So what’s the answer? Meyer thinks he knows:

How do we relate to reality? How do we begin to comprehend it? By using that same marvelous brain our ancestor used. By the exercise of memory. How do we take stock of these memories? By reading, Travis. Reading! Complex ideas and complex relationships are not transmitted by body language, by brainstorming sessions, by the boob tube or the boom box. You cannot turn back the pages of a television show and review part you did not quite understand. You cannot carry conversations around in your coat pocket.

Ha! What would MacDonald have to say about Tivo and iPhones?

Meyer is worried, he tells Travis, that non-readers are disenfranchised, cut off from any knowledge of history, literature and science. And worse, they become negative role models for their children, who will in turn, “become a new generation of illiterates, of victims.”

“The non-reader, Travis, wants to believe. He is the one born every minute. The world is so vastly confusing and baffling to him that he feels there has to be some simple answer to everything that troubles him. And so, out of pure emptiness, he will embrace spiritualism, a banana diet, or some callous frippery like Dianetics.”

Or worse. Name your modern opiate.

MacDonald died Dec. 28, 1986, a few months after finishing the essay. I really wonder what he might think of where we are today, of what he might think watching those blank-eye folks on the beach, trying to think of one author’s name. What would he make of the fact we are barraged with information twenty-four hours a day, yet we seem to be growing not smarter but more lost and disconnected?

The essay ends with Meyer saying that he has no cure to offer, but that just identifying the disease is a good first step. But then he adds:

“Bleak, my boy. Bleak indeed. And so let us trudge back toward home, and stop at the bar at the Seaview for something tall and cold, with rum in it.”

“Beautifully said,” I told him.

On the way back, I told him that he had made me feel guilty about my frivolous reading fare of late, and what might I read that would patch up my comprehension and my conscience at the same time.

Meyer thought about it until we had our drinks. He took a sip, sighed, and said, “I’ll lend you my copy of Barbara Tuchman’s A Distant Mirror.”

I am halfway through it. And the world has a different look, a slightly altered reality. That fourteenth century was the pits!

I ordered the Tuchman book from Amazon. (My local bookstore can’t get it, I tried). Now I am going to go mix a stiff gin and tonic, crack it open and try to get some badly needed sense of perspective.

Happy reading, folks. By the way, I am on the road today, probably somewhere near the Michigan-Indiana border as you read this. So if I can’t reply quickly, please chat among yourselves. Will check in when I get home to Traverse City, MI.