by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Last week we talked about the “telling detail,” and the power it adds. We gave some tips on how to craft such moments. That requires a thing called work.

Last week we talked about the “telling detail,” and the power it adds. We gave some tips on how to craft such moments. That requires a thing called work.

Today we’re going to ask: is it worth the effort?

This query comes out of a post by Mr. Joe Konrath. He was, most of you will remember, one of the earliest and most enthusiastic adopters of self-publishing. He was also a prolific blogger, and not one to shy away from a strong opinion. Then, a couple of years ago, he went silent. Now he’s back, and clearly he’s lost none of his verve, as evidenced by his post On Writing S*** (this being a family blog, I have made a slight edit to the title).

The gist of the piece is that it may be pointless for today’s writer of indie fiction to spend too much time trying to improve the quality of his writing:

My first drafts are pretty good. They’re lean, and fast, and the character arcs and plot rarely need tweaking. The rewrite polish is mostly spent on housekeeping stuff; adding color, exploding certain scenes, adding more drama to the climax, salting in a few more jokes, changing word choices, putting in a few more clues or callbacks.

And sometimes a book is short, say around 60k words, I’ll spend time expanding some scenes or adding a few to beef it up to 70k+, because I want to give good value to the readers who still pay for my stuff rather than read it via KU.

So I spend a full 1/3 of my time as a writer trying to make a grade B book into a grade A book.

I think I’m wasting my time.

He goes on to say that readers of an author will stick with that author even if subsequent books in a series are not as good as the first few. His argument, broken down, goes like this:

Better isn’t actually better.

More is better.

Faster is better.

Flash beats substance.

Loyalty trumps all.

Konrath’s main exhibit is his wife’s reading habits. She will stick with an author she has liked in the past, even if the author’s new books aren’t so hot.

To be clear, Konrath’s post does not actually advocate its title. He does not think you can write pure dreck and get away with it. He says he couldn’t live with producing a work that’s “less than a grade C … But I could live with Bs. I was fine with getting Bs in school. Why put in all that extra work to turn a B into an A when I won’t lose readers for a B?”

It’s a good question, so let’s talk about it. A few reflections:

- Several A-list, traditionally-published writers have, over the last several years, “mailed it in.” Some have kicked up their output to satisfy publishers, who need them more than ever for the ol’ bottom line. Some of these more recent books have wider margins and fewer total words. Yet still they sell…though perhaps with some fall off, if reviews are any indication.

- A little fall off from an A-list writer still brings in big bucks.

- More is better does not always pay off. You still have to meet a certain minimum of storytelling skill.

- There many prolific indies (Konrath is one) who do have the skill and thus make more money the more they produce.

- For me, pride plays a role. I worked hard on a traditionally published legal thriller trilogy I’m very proud of. Indeed, I think the last line of the last book is the most perfect ending of my career. I re-wrote that last scene at least a dozen times. I’d do it again to gain the same effect. (FYI, the first book of the trilogy, Try Dying, is free today in the Kindle store).

- I write a book and work on it until I think it’s the best I can do within a time limit. I’ve got SIDs (self-imposed deadlines) and readers who want more of my stuff. Sometimes I miss a SID.

- If I miss a SID, I don’t cancel my contract. I do give myself a stern talking-to.

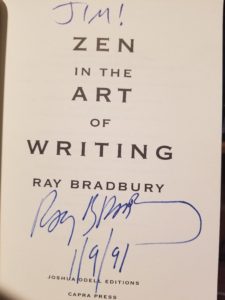

- I write to entertain, and for me that includes going for what John D. MacDonald called “unobtrusive poetry” in the style. This requires, once again, work.

- I also like being prolific which, in the “old days,” meant a book a year. As an indie, I can do more, and also include a regular output of short fiction.

- “The most critical thing a writer does is produce.” — Robert B. Parker.

So…where do you come out on this scale of craft, care, prolificity, faster, better?

Do you stick with an author or series no matter the quality of recent books?