Purchased from iStock by Jordan Dane

I really liked TKZ contributor Debbie Burke’s Feb 5th post “Eight Tricks to Tap into your Subconscious for Better Writing.” The mind is an interesting resource for writers. I’ve heard other authors say they dreamed a plot or how certain insights come to them while they sleep. I’ve personally had strange experiences in what I call “twilight sleep,” the realm between sleep and fully awake.

Many experts on dream studies say that dreams exist to help us solve problems we’re experiencing in our lives, or can help us tap into memories and process emotions. It’s possible that if you go to bed with a troubling thought – like a plot point that’s implausible or a character motivation that doesn’t feel right – sleep will allow your mind to come up with a resolution by the time you wake up.

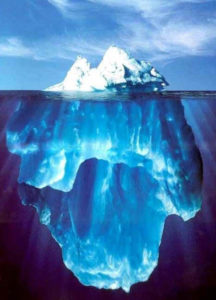

Our own James Scott Bell has a term for this phenomenon. He calls the working brain at night – the boys in the basement. They don’t need to sleep. I’ve experienced this many times. That’s why I keep notepads near my nightstand or jot down ideas on my phone when they come to me after I wake up.

LUCID DREAMS

Have you ever sensed you were dreaming INSIDE of a dream? You might’ve experienced a “lucid dream.” Research has shown that lucid dreaming is accompanied by an increased activation of parts of the brain that are normally suppressed during sleep. Lucid dreaming represents a brain state that falls between REM (rapid eye movement) deep sleep and being awake.

Some people who are lucid dreamers are able to influence the direction of their dream, changing the story, in a manner of speaking. While this may be a good tactic to take, especially during a nightmare, many dream experts say don’t force it. It’s better to let your dreams occur naturally.

HYPNAGOGIA

Hypnagogia is the transition between wakefulness and sleep. It’s what I call “Twilight Sleep” and it has nothing to do with sparkling vampires. It’s a state of mind where you may experience lucid dreaming.

In this state, you can tap into all the good ideas you have stored up, uninhibited by rational thought and insecurities. You’re open to all things. It’s how authors can go to bed knowing our manuscript has a flaw, but not knowing how to fix it. Our mind (or the boys in the basement) come to our assistance during the night when we are open to ideas.

Hypnagogia can also manifest in other ways, like when we may hear strange noises in our house–at the moment we wake up–and we KNOW someone has broken in. This could explain the monsters in our closet when we were kids or how we see dangers hidden in the shadows of our room. We’ve tapped into the primitive primal fear that animals experience where they trust their instincts (in order to survive) and react on pure reflex.

I have an experience like this and never forgot it. It happened in the afternoon while I was napping after a long exhausting day at work. I had the sensation that I was dreaming inside a dream, but I was certain someone was in the empty room with me. I even felt the bed move when they sat next to me. I got the sense they were staring down at me. I was so terrified (my body reacted with the fear – my heart raced and my lungs heaved) that I refused to open my eyes. I was so sure my nightmare would be confirmed. I sensed being touched, but still, I didn’t open my eyes. I never did. But I never forgot the feeling of abject, paralyzing fear and have written it into my stories.

Hypnagogia might possibly be one of the mind’s most vital tools for creativity and for tapping into the words to describe the high tensions or emotions we need to write a scene we may never had experienced personally.

How do we tap into Hypnagogia when we need it?

I believe it takes time to train our minds to open like this, but it could be a good exercise. I know that when I first started writing, I had to tap into my brain to hear dialogue from my characters and visualize each scene. Over time I got better at it. Now it’s impossible for me to be in public. I have no filter between my brain and my mouth. Have any of you experienced this? Oy. It can be a curse, but no regrets. I love how it works when I write–so worth it.

Some authors use image boards to trigger their imagination for the world they are creating, but what if you could tap into twilight sleep and manipulate ideas in your mind – to imagine them more deeply? Find a dark room in the afternoon and relax. Shut your eyes and clear your mind. I sometimes visualize numbers floating in the darkness behind my closed eyelids and count down until I am completely relaxed.

You don’t want to fall asleep, so you might consider holding something that will wake you if it falls. Salvador Dali used to hold steel balls that would make a noise when they dropped. Thomas Edison used to hold a metal ball over plate tins that would cause a racket if he let them drop. Test what works best for you in this process.

Does it help to record your results immediately after? A nearby notepad could help solidify your ideas visually as you write them down. Try these sessions for a short period and make the most of them as you get better. I find that if nothing else, the quiet time is good for the soul.

Tips to Recall Your Dreams

If you are a sound sleeper and don’t wake up until the morning, you are less likely to remember your dreams compared to people who wake up several times in the night. Try these tips to improve your ability to remember your dreams:

1.) Wake up without an alarm. You are more likely to remember your dreams if you wake up naturally than if you use an alarm. An annoying alarm can shift your focus to turning the blasted thing off and away from your dream.

2.) Tell yourself to remember. If you want to recall your dreams and make a fully aware decision to do so, you are more likely to remember your dreams in the morning. Before you go to sleep, tell yourself that you want to remember your dream. It may take practice.

3.) Dream playback. If you think about the dream right after waking, it may be easier to remember it later. Which has worked best for you? Making note of it immediately after or is it better to have patience and recall it later?

SUMMARY – This may seem odd if you hadn’t considered it before, but if you’ve been writing for years, can you recall how much your imagination has grown since the beginning? How has your process changed over the years? Have you noticed the changes? As I write, I find it easier to tap into my imagination now than when I first started out. Like I said, my mouth has no filter, by design. This is a good thing as a writer. Not so much if you hang around normal people.

FOR DISCUSSION

1.) Has anyone experienced Hypnagogic writing? What were the results?

2.) Do you know anyone who has experienced dreams that they used in their writing? Has it happened to you? Tell us about it.

Before the holidays, one of our beloved TKZers requested a blog post that offered helpful tips in series writing.

Before the holidays, one of our beloved TKZers requested a blog post that offered helpful tips in series writing.