“Begin at the beginning,” the King said gravely, “and go on till you come to the end: then stop.”

By PJ Parrish

I had a whole ‘nother blog in the works today but Clare’s post yesterday on common amateur mistakes made me want to switch gears. That, and the fact that I was hearing voices in my head the other day and this is a good way to exorcise them.

A while back, I gave a talk to a beginning writers group about what makes for a great opening in a novel. We had a good time analyzing which of their openings had promise or why they had veered off track. It’s a popular topic, as we at TKZ here so well know, but I think it’s one that we all need to revisit constantly. Me included.

See, the other day, as I was pounding around the jogging oval at the park, I heard a strange voice whispering in my head. I had never heard her before, but she was insistent: “Tell my story! Tell my story!” I tried to ignore her, because as Kelly and I await the Sept. 9 launch of our new book SHE’S NOT THERE, we are 16 chapters into a new Louis Kincaid. And one of the commandments of novel writing is Thou Shall Finish One Book Before Starting a New One. But this woman wouldn’t shut up, so I went home and banged out 2,000 words. Wow! I never get out of the gate that fast! I was chuffed.

Well, I re-read it yesterday. Wee-doggies, it stinks. I open with a woman sitting alone in a fishing boat in the Everglades. She is thinking about her life and what brought her to this point. She is sad. She is regretful. She is boring as hell. I also larded in pages of description of the saw grass, the weather, the clouds, the water, even the type of fishing lure she was using. Finally, toward the 2,000-word mark, I reveal she is a Miami homicide detective who turned in her badge when her husband and child were killed in a drug deal gone bad that she was involved in.

This morning, I deleted the chapter. Lesson number 1: Just because you have an idea doesn’t mean you should act on it. Lesson number 2: Even experienced writers have trouble with openings.

Even Stephen King. You think you sweat bullets over openings? He says he spends months and even years before he finds his footing. I read this recently in an interview King gave to The Atlantic magazine. He talks at length about what makes for a great opening, and how hard it is for him to find the right one.

When I’m starting a book, I compose in bed before I go to sleep. I will lie there in the dark and think. I’ll try to write a paragraph. An opening paragraph. And over a period of weeks and months and even years, I’ll word and reword it until I’m happy with what I’ve got. If I can get that first paragraph right, I’ll know I can do the book.

And he makes a great point, that the right opening line is as important to the writer as it is to the reader:

You can’t forget that the opening line is important to the writer, too. To the person who’s actually boots-on-the-ground. Because it’s not just the reader’s way in, it’s the writer’s way in also, and you’ve got to find a doorway that fits us both. I think that’s why my books tend to begin as first sentences — I’ll write that opening sentence first, and when I get it right I’ll start to think I really have something.

Which is why I deep-sixed my woman in the fishing boat. Maybe her story does need to be told, but I entered via the wrong door. I’m going to set her aside for a while. In the meantime, I am going back to school. Want to come along?

HOOKS

Enthuse or lose! What was the prime crime of my bad chapter? NOTHING HAPPENED! The first chapter is where your reader makes decision to enter your world. Your hook needn’t be too fast or fancy. It can even be quiet — like someone going on a fishing or hunting trip (see example below!). But it must be suspenseful enough to makes us care about your character. Fancy hooks can be disappointing if what follows doesn’t measure up. If you begin at the most dramatic or tense moment in your story, you have nowhere to go but downhill. Also, if your hook is extremely strange or misleading, you might just make the reader mad.

What about opening with action scenes? I’ve seen it work well; I’ve seen it look silly. I think intense action scenes work only if they have context and reason for happening. Car chase, bullets fly, things explode, dead bodies! But unless you give reader reason to care about someone, it feels cheap and pushy, like a Roger Moore James Bond movie. If you can make us CARE about the person during intense opening action scene, yes. If not, it’s boring and trite.

OPENING LINES

A good one gives you intellectual line of credit from the reader: “Wow, that line was so damn good, I’m in for the next 50 pages.” A good opening line is lean and mean and assertive. One of my fave’s is from Hemingway’s story, “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber: “It was lunch now and they were all sitting under the double green fly of the dining tent pretending that nothing had happened.”

A good opening line is a promise, or a question, or an unproven idea. But if it feels contrived or overly cute, you will lose the reader. Especially if what follows does not measure up. Stephen King has two favorite opening lines. One is from James M. Cain’s great novel The Postman Always Rings Twice: “They threw me off the hay truck about noon.” Here’s King on why he loves it:

Suddenly, you’re right inside the story — the speaker takes a lift on a hay truck and gets found out. But Cain pulls off so much more than a loaded setting — and the best writers do. This sentence tells you more than you think it tells you. Nobody’s riding on the hay truck because they bought a ticket. He’s a basically a drifter, someone on the outskirts, someone who’s going to steal and filch to get by. So you know a lot about him from the beginning, more than maybe registers in your conscious mind, and you start to get curious. This opening accomplishes something else: It’s a quick introduction to the writer’s style, another thing good first sentences tend to do.”

GET INTO STORY AS LATE AS POSSIBLE

This is one of my pet peeves about bad writing…throat clearing. Begin your story just moments before the interesting stuff is about to happen. You want to create tension as early as possible in your story and escalate from there. Don’t give the reader too much time to think about whether they want to go along on your ride. Get them buckled in and get them moving. Preferably not in bass boat.

INTRODUCE THE PROTAGONIST

Another pet peeve of mine. Don’t wait too late in the story to introduce your hero. Don’t give the early spotlight to a minor character because whoever is at the helm in chapter one is who the reader will automatically want to follow. I call these folks “spear carriers” after the guys who stand in the background holding the spears in “Aida.” They aren’t allowed to steal the spotlight when Radamès is belting out Celeste Aida. So don’t let your secondary characters get undue attention or the reader will feel betrayed and annoyed when you shift the spotlight.

IDENTIFY THE CONFLICT OR QUEST

Begin the book with conflict. Big, small, physical, emotional, whatever. Conflict disrupts the status quo. Conflict is drama. Conflict is interesting. Your first chapter is not a straight horizontal line. It’s a jagged driveway leading up a dark mountainside. Don’t put a woman in a fishing boat in the Everglades thinking about how crappy her life is and expect the reader to care.

WHAT IS AT STAKE HERE?

What is at play in the story? What are the costs? What can be gained, what can be lost? Love? Money? One’s soul? Will someone die? Can someone be saved? The first chapter doesn’t demand that you spell out the stakes of the entire book in neon but we do need a hint. And we don’t care that her fishing lure is a 1-ounce jig with a bulky trailer.

CREATE A DRAMATIC ARC

Your whole book has an arc, but every chapter should have a mini-arc. Ask yourself “What is the purpose of this chapter?” and then build your chapter around that. This does not mean each chapter needs a conclusion but it needs to feel complete unto itself even as it compels the reader onto the next chapter. The opening chapter should have its own rise and fall. It is not JUST A LAUNCHING PAD!

GET YOUR CHARACTERS TALKING

Dialogue is the lifeblood of your story and you need it early. Too much exposition or description is like driving a car with the emergency brake on. Likewise, don’t bog down your opening with characters doing menial things. Like fishing. Or thinking about boring stuff. Like fishing lures. Here’s some good advice from agent Peter Miller that I read once on Chuck Sambuchino’s Writer’s Digest blog: “My biggest pet peeve with an opening chapter is when an author features too much exposition, when they go beyond what is necessary for simply ‘setting the scene.’ I want to feel as if I’m in the hands of a master storyteller, and starting a story with long, flowery, overly-descriptive sentences makes the writer seem amateurish and the story contrived. Of course, an equally jarring beginning can be nearly as off-putting, and I hesitate to read on if I’m feeling disoriented by the fifth page. I enjoy when writers can find a good balance between exposition and mystery. Too much accounting always ruins the mystery of a novel, and the unknown is what propels us to read further.”

SO DOES THAT MEAN I SHOULD OPEN WITH DIALOGUE?

This goes to personal taste. I’m not a fan of it, but I have seen it pulled off. But be careful because opening with dialogue tosses the reader into the deep end of the fictional pool with no tethering in time and place. This is like waking up from a coma. Where am I? Who are these people talking? I could be wrong because I haven’t read them all, but even Dialogue Demon Elmore Leonard gives you a quick couple lines or graphs first. (Okay, I’m wrong: LaBrava opens with “He’s been taking pictures three years, look at the work,” Maurice said.) But if your dialogue only leads to confusion, that isn’t good. Which relates to…

ESTABLISH YOUR SETTING AND TIME FRAME

The first chapter must establish the where and the when of the story, just so the reader isn’t flailing around. Yes, you can use time and place taglines, especially if your story is wide in geographic scope or bouncing around in time. But if your story is fairly linear and compact (taking place, say, all within six months time in Memphis), sticking a time tag on each chapter only makes you look like you don’t know how to gracefully slip this info into your narrative.

ESTABLISH YOUR TONE AND MOOD

First impressions matter. From the get-go, your reader should be able to tell what kind of book he is reading – hardboiled, romantic suspense, humorous, neo-noir? Yes, the cover and copy conveys this, but you need to convey it in your opening. Everything in your book should support your tone, but the first chapter is vital to inducing an emotional effect in your reader. I’ve mentioned Edgar Allan Poe’s Unity of Effect often here but it’s worth repeating: Every element of a story should help create a single emotional impact. But remember that a little mood goes a long way – think of a few swift and colorful brush strokes rather than gobs of thick paint. Did you know that in the Everglades, intense daytime heating of the ground causes the warm moist tropical air to rise, creating the afternoon thundershowers? And that most of the storms happen at 2 p.m.? I should have just wrote “It rained in the afternoon.”

MAKE YOUR VOICE LOUD AND CLEAR

This is where you are introducing your story but also yourself as a writer. Your language must be crisp, you must be in complete control of your craft, you must be original! Shorter is usually better. No florid language or indulgent description, no bloated passages, no slack in the rope. The reader must feel he is being led by a calm, confident storyteller. See quote about by Stephen King about James M. Cain.

BACKSTORY AND EXPOSITION

The first chapter is not the place to tell us everything. Don’t be like a child overturning his bucket of toys — then it’s just a colorful clamor, an overindulgence of information. Exposition kills drama. Backstory is boring. Give us a reason to care about that stuff before you start droning on and on about it. Incorporating backstory is hard work, but you must weave it artfully into the story not give us an info-dump chapter 1.

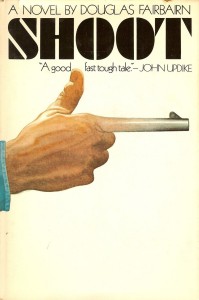

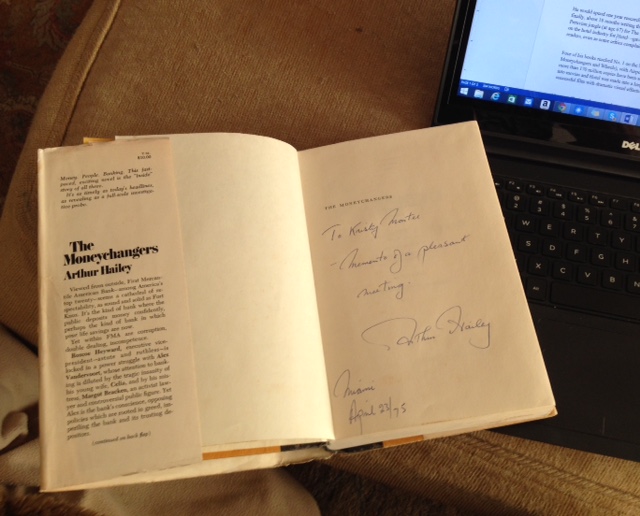

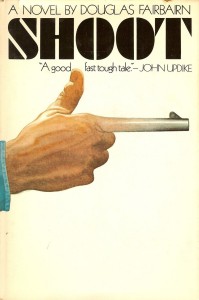

To end, let’s go back to Stephen King. So we know he admires James M. Cain. But what is his all-time favorite opening line? It is from Douglas Fairbairn’s novel Shoot. Here’s the set-up: A group of middle-aged guys, all war vets, are on a hunting trip. As they come to a riverbank, they spot another group of guys, much like themselves, on the other side. Without any provocation, one of the hunters on the opposite bank raises his rifle and fires at the first group, wounding one man. Reflexively, one of the first group returns fire, blowing the shooter’s head apart. The opening line: “This is what happened.”

And here is King on why he loves it:

“This has always been the quintessential opening line. It’s flat and clean as an affidavit. It establishes just what kind of speaker we’re dealing with: someone willing to say, I will tell you the truth. I’ll tell you the facts. I’ll cut through the bullshit and show you exactly what happened. It suggests that there’s an important story here, too, in a way that says to the reader: and you want to know. A line like “This is what happened,” doesn’t actually say anything–there’s zero action or context — but it doesn’t matter. It’s a voice, and an invitation, that’s very difficult for me to refuse. It’s like finding a good friend who has valuable information to share. Here’s somebody, it says, who can provide entertainment, an escape, and maybe even a way of looking at the world that will open your eyes. In fiction, that’s irresistible. It’s why we read.

King loves it so much, he echoed it in the opening of of his own novel Needful Things: “You’ve been here before.” And guess what? It’s his own favorite opening. Which is a good place to end, I think.