As a retired police officer and now starving artist writer, I pay attention to others who write true crime and crime fiction. I read (actually skim) more for craft than story because I’m still very much in the learning curve when it comes to writing. Like the investigation business, I think a writer never stops discovering new techniques and benefiting from mistakes. A regular flaw I see in reading some crime publications—the writer just doesn’t know how to speak cop.

Every vocation has its lingo. In my shadow life, I’m a ticket-holding marine captain. An old boat skipper. I know Sécurité, Pan-Pan, and Mayday-Mayday-Mayday. They’re common emergency calls in the airplane world, as well. Industries like film production have their unique terms like Rigger, Gaffer, and Abby Singer Shot. And the sex trade has… well…

I think that in writing convincing crime stories, whether true or false, it’s critical to get the cop-speak right—specific to the specific location (as variances exist). Part is not being scared to use to F-word because all cops and crooks swear. The trick is using it sparingly and not mimicking a realistic alcohol-fueled-end-of-the-night party at a truck loggers convention. Trust me. I’ve been to one.

Setting profanity aside, there are day-to-day conventions in police terminology. Some writers get it right. Some don’t. The difference is in research, connections, understanding locality, and personal experience. Here are the basics in how to speak cop. Version 1.0.

Radio Procedure – The Ten Code

I’ve never heard of an English-speaking police department that doesn’t use some sort of ten code on the radio. Some officers are so indoctrinated that they write tens in their reports. The reason for a ten code radio procedure is brevity. It’s not for secrecy. That’s a whole different matter with encrypted devices and mission-specific codes. Here are the most common ten codes that seem to be universal.

I’ve never heard of an English-speaking police department that doesn’t use some sort of ten code on the radio. Some officers are so indoctrinated that they write tens in their reports. The reason for a ten code radio procedure is brevity. It’s not for secrecy. That’s a whole different matter with encrypted devices and mission-specific codes. Here are the most common ten codes that seem to be universal.

*Note – 10-Codes greatly vary between jurisdictions. These are the most common ones*

10-1 — Unable to copy

10-4 — Copy, Yes, Affirmative, Acknowledged

10-6 — Busy, Occupied, Tied-up

10-7 — Stopped, At scene, Out of vehicle

10-8 — Back in service, Available for calls

10-9 — Repeat, Say again, I didn’t understand

10-10 — Negative, No, It’s BS

10-12 — Stand by, Stop transmitting

10-19 — Return to, Go back

10-20 — Location

10-21 — Call by phone

10-22 — Disregard, Fuhgetaboutit

10-23 — Arrived at Scene

10-27 — Driver license info requested

10-28 — Vehicle plate info requested

10-29 — Check person/vehicle/article for wanted

10-33 — Emergency! Officer Down! Officer in Peril!

10-60 — Bathroom Break

10-61 — Coffee break

10-62 — Meal break

10-67 — Unauthorized listener present

10-68 — Returning to office (RTO)

10-69 — Breathalyzer operator required

10-100 — I have no f’n idea what you’re talking about

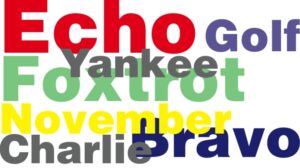

The Phonetic Alphabet

I see this screwed-up so often. Some attempts are quite creative. Amusing, if not hilarious. “Bob” for B is real common. So is “Dog” for D. But, I’ve heard “Banana” and “Dillybar”, and I’ve heard “Limmo” for L, “Monica” for M, and more “Nancy” than I can count. Then there’s “Sylvester-as-in-Stallone”, “Tattoo”, and “Ugly”. Here are the right phonetic alphabet radio calls (worldwide):

I see this screwed-up so often. Some attempts are quite creative. Amusing, if not hilarious. “Bob” for B is real common. So is “Dog” for D. But, I’ve heard “Banana” and “Dillybar”, and I’ve heard “Limmo” for L, “Monica” for M, and more “Nancy” than I can count. Then there’s “Sylvester-as-in-Stallone”, “Tattoo”, and “Ugly”. Here are the right phonetic alphabet radio calls (worldwide):

Note: Phonetic alphabet pronunciations vary in regions. These are the universal ones that international transportation uses.

A — Alpha

B — Bravo

C — Charlie

D — Delta

E — Echo

F — Fox or Foxtrot

G — Golf

H — Hotel

I — India

J — Juliet

K — Kilo

L — Lima

M — Mike

N — November (not Nancy)

O — Oscar (not October)

P — Papa (not Penny or Pork Chop)

Q — Quebec

R — Romeo

S — Sierra

T — Tango

U — Uniform

V — Victor

W — Whisky

X — X-ray

Y — Yankee

Z — Zulu

The Rank System

There are two main ranking systems in the western police world. One is the constabulary like used in British Commonwealth countries. The other is military which is common in U.S. jurisdictions. Both are top-down rankings where they start with an omniscient power that oversees minions. Here are typical organizational charts for the two structures.

There are two main ranking systems in the western police world. One is the constabulary like used in British Commonwealth countries. The other is military which is common in U.S. jurisdictions. Both are top-down rankings where they start with an omniscient power that oversees minions. Here are typical organizational charts for the two structures.

Constabulary Commissioned Officers

Commissioner

Deputy and Assistant Commissioners

Superintendents

Inspectors

Constabulary Non-Commission Officers

Staff Sergeants

Sergeants

Corporals

Constables

Military-Style Police Officers

Chiefs

Deputy Chiefs

Colonels

Majors

Captains

Lieutenants

Sheriffs

Military-Style Police Rank & File

Sergeant

Detective Sergeant

Detective

Deputy

Officer

General Cop Speak

I see a lot of crime books where the protagonist is a high ranking police officer like a DCI (Detective Chief Inspector) or a Precinct Captain. These sound good and powerful, but the reality in police investigations is the grunts do most of the work. Detectives, Beat-Officers, and Constables go out there and arrest suspects, interrogate them, and then get their butt roasted in court.

I see a lot of crime books where the protagonist is a high ranking police officer like a DCI (Detective Chief Inspector) or a Precinct Captain. These sound good and powerful, but the reality in police investigations is the grunts do most of the work. Detectives, Beat-Officers, and Constables go out there and arrest suspects, interrogate them, and then get their butt roasted in court.

Commissioners are politicians and serve at the pleasure of their master. Superintendents, Sheriffs, and Inspectors are budget-driven paper-pushers. Most Staff Sergeants and Captains spend more time on HR matters than criminal overseeing. It’s the Lieutenants, Sergeants, and Corporals that supervise the police workhorses—the deputies, constables, and officers.

I could go on about cop-speak like surveillance terms. “R-Bender”. “Stale Green”. “Crowing”. “Taking Heat”. Or, administrative stuff that takes up most of the time. “Per-Form”. “C-264B”. And, “Leave Pass”.

Cop Speak Resource

I’m steering you to B. Adam Richardson. Adam is a still-serving detective with a Southern California Police Department. Adam can’t reveal his true name or actual location because of security reasons, but Adam runs two Facebook sites dedicated to helping crime writers get it right. Here’s the link to Writers Detective and his FB rules:

https://www.facebook.com/groups/WRITERSDETECTIVE/

“There has been some discussion in this group about what the rules are. Since my day job is all about enforcing rules, I wanted to let this group grow on its own and develop its own feel without me having to create rules.

I have seen other groups that are nothing more than mean/cynical replies to honest questions and spammy book promos. I hate those.

For the most part, I have been quite happy that this has grown into a very supportive group. I want our atmosphere of support and the celebrating of writing milestones to continue.

Although I am the one that started this group, I don’t own this group. You do. The intended purpose of this group is for writers like you to find the law enforcement related answers you’re looking for. I try my best to keep up with the Q&A, but I can’t answer every question. The beauty of this group is leveraging the collective experience and/or research of the membership. So, allow me to clear something up:

Anyone can post a question or an answer in this group.

We have a wealth of collective knowledge and experience in here. I know our members include a former CSI tech, a criminal defense attorney, a former MP, a former Coroner, and a ton of crime-fiction writers with solid research into serial killers, forensic science, and criminal psychology. That’s just the members I know about and that doesn’t even include the cops in the group. You do not need to be a cop to answer questions in here.

Yes, the quality of the answers will vary. I want to recognize that everyone offering an answer is doing so to help a fellow writer and spark discussion.

Many have come to this group seeking answers from a cop’s perspective and we’ll continue to offer that. I fully admit that answers coming from a cop’s perspective aren’t always right either. (Just ask a defense attorney.)

Often, the reality of how things play out on the street is very different from how textbooks and courtroom testimony portray things. We (the cops in this group) do try our best to give you the truth of what we’ve seen and experienced. I just ask that you recognize that our answers may differ from what research into a subject indicates. Research, textbooks, and courtroom testimony often paint things in black and white, while reality is a blur of varying shades of gray. Recognizing these differences are key to identifying and capturing realism for your own stories.

Sure, there may be answers posted that are solely based upon what someone saw in an episode of Miami Vice or CSI…but I’d prefer to not censor answers, especially when the poster’s intention was to be helpful. It is up to you to figure out what is relevant, factual, and useful for your own writing projects.

I propose we start using our Like buttons to act like a Reddit/Quora style “up-vote” on best answers to a particular question.

There may be some debate over answers, but that is to be expected. We can all learn from civil discussions about the issues at hand. These debates happen in criminal justice all the time; it’s the very basis of our judicial process. ~ Adam”

Adam R. also has a FB site at Writers Detective Bureau. Check out this link:

https://www.facebook.com/writersdetective/

So, that’s it for How To Speak Cop — Version 1.0. Anyone interested in a more detailed post… Version 2.0 ?

— — —

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective with a second career as a forensic coroner. Now, Garry has re-invented himself as a writer with a based-on-true-crime series on cases he was involved in. Check out Garry Rodgers on his Amazon Author Page, Twitter, Facebook, and his website at DyingWords.

Garry Rodgers is a retired homicide detective with a second career as a forensic coroner. Now, Garry has re-invented himself as a writer with a based-on-true-crime series on cases he was involved in. Check out Garry Rodgers on his Amazon Author Page, Twitter, Facebook, and his website at DyingWords.

Garry’s newest book in the true crime series, On The Floor, will be out in mid-August 2020.