Category Archives: Writing

…Reflection…Giving…Planning

Past, Present, and Future

Leave a Legacy

By Steve Hooley

It is the time of year when we reflect on the past, give gifts during the holidays, and plan for the future. So, how does that relate to writing? Can we learn from the history of writing to plan for the future of our writing? It has been said, “Those who fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it.” (Winston Churchill, 1948, a paraphrase from George Santayana, 1905). And from geometry we learn that it takes two points to define the trajectory of a line. Could those two points be the past and the present? And does the trajectory of that line give us any clues about the future?

The Past – Reflection

For the past, we turn to British and American literature. Now, I am out of my element on this topic. I studied math and science in college. So, those of you English and literature experts, please help me out here.

For a listing of the periods or eras in British and American literature, I turned to Wikipedia. Here is what I found:

British Literature – periods and eras

Old English lit. – 658-1100

Late Medieval – 1066-1485

Renaissance

- Elizabethan era – 1588-1603

- Jacobean period – 1603-1625

- Late Renaissance – 1625-1660

The Restoration – 1660-1700

18th Century

- Augustan age – 1701-1798

- Roots of Romanticism – 1750-1798

Romanticism – 1798-1837

Victorian lit. – 1832-1900

Twentieth Century

- Modernism and cultural revival – 1901-1945

- Late modernism – 1946-2000

21st Century lit.

American Literature

Colonial lit.

- Early prose

- Revolutionary period

Post-independence

- First American Novel

19th Century – Unique American style

Late 19th Century – Realist fiction

20th Century prose

- 1920s

- 1930s – Depression era

Post WWII fiction

- Novel

- Short story

Contemporary fiction

I have gone back and reread “classics” from the 1800s in my attempt to educate myself. I have been surprised repeatedly by how much styles have changed from then until now. Many of those books contain techniques which we are now encouraged to avoid: omniscient POV, head-hopping, author intrusion, slow pace and entry into the story, lengthy description, tell don’t show, etc.

There were many cultural, societal, and economic reasons why those styles worked then, but wouldn’t work now. What can we learn from them?

Before we move from past to present, here is a link to John Gilstrap’s post from three days ago. John’s post It is a fantastic history of the publishing industry over the past quarter century.

The Present – Giving

We give gifts in the present. Do you consider your books and stories a gift to the future? If a gift is handed down to descendants and it is considered to be of value, it is a “legacy.” Are your books a legacy? Do you want them to be a legacy?

On a side note, but still about giving, today is “Goose Day.” If you investigate the secular tradition of “The Twelve Days of Christmas” and gift giving, you discover that we start with the 12th gift on December 13th and work our way down to the 1st gift on December 24th. This is December 19th, so if you are looking for a gift for your “true love,” it’s six geese a layin’ today. And hopefully, some of those geese will be layin’ gold eggs. Now, that’s a legacy.

The Future – Planning

If we wish our books/stories/wisdom to be a legacy, of value for the future, and maybe for us if we’re still around, how do we plan for that? Does our writing, or the way we publish, need to change? Can we predict trends for the future based on what has happened in the past and what is happening now? How will writing, publishing, and reading change? And how do we best position our writing to be ready for those developments?

- What era/period from the past would you choose to write in, if you could choose?

- Why did you pick that era/period?

- What new developments for writing/publishing/marketing/reading do you see coming in the future?

- Do you plan to position yourself for coming trends? How?

- Publishers Weekly says it’s about “what’s new and what’s next.” If you subscribe, what can you share about expected coming trends?

What’s on Your Nightstand?

There’s a saying that goes, “Where you’ll be five years from now depends on the people you meet, the conversations you have, and the books you read”. I don’t know who said it, but I say it holds truth. Especially books you read… like the ones on your nightstand.

I’ve always been a reader. Not sure if the right adjective is voracious, avid, or anal, but I love to read. It’s in my blood, and the blood I begat, and the blood I married. My family members are all readers. So are most of my friends and colleagues.

My dad got lost for hours reading everything from newspapers to classics. My sister, who’s a lioness of a reader, said if my dad were alive when the internet arrived, we’d never have gotten him off it. My mum held a Masters in English Lit, and she wrote her thesis on Thomas Hardy. To no surprise, mum was a teacher who loved to teach kids to love to read.

Our kids were very young when they were born, so it was easy for my wife and I to mould them into our reading cult. I turned Aesop’s Fables into “stupid stories” to get bedtime bladder-relieving belly laughs from Emily and Alan. Rita, my wife, sensibly read Harry Potter to them so convincingly that they hated the movies because they didn’t sound like their mom’s character versions.

Our kids were very young when they were born, so it was easy for my wife and I to mould them into our reading cult. I turned Aesop’s Fables into “stupid stories” to get bedtime bladder-relieving belly laughs from Emily and Alan. Rita, my wife, sensibly read Harry Potter to them so convincingly that they hated the movies because they didn’t sound like their mom’s character versions.

Now our kids are all growed up. Thankfully, they turned out all right because they’d rather read than work, and that’s proven because both took leave from their jobs and went back to university. At least this time, mom and dad aren’t paying.

Now mom and dad are empty nesters who love nothing better than hang around and read. Rita and I read a lot. We have so many books that our insurance provider required a structural engineer to approve our book cases for fear of someone being killed in a catastrophic collapse.

Now mom and dad are empty nesters who love nothing better than hang around and read. Rita and I read a lot. We have so many books that our insurance provider required a structural engineer to approve our book cases for fear of someone being killed in a catastrophic collapse.

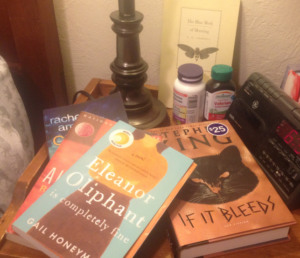

Seriously, though, we have serious stuff on our nightstands. But as close as Rita and I have been during our 37 married years, we have significantly different reading interests. Same with our kids—Emily, 32 and Alan, 30—and that’s a good thing because we all keep on reading.

My wife and kids stepped up for this Kill Zone piece. I polled them on their nightstands. I asked them to list five books they recently read, were currently reading, or had purchased and intended to read next (the TBR list). Here’s five reads on each of the Rodgers family nightstands.

Garry Rodgers

- Podcasting For Dummies — Tee Morris / Chuck Tomasi (Take note, Sue Coletta) 🙂

- Profiles in Folly – History’s Worst Decisions & Why They Went Wrong — Alan Axelrod

- Sapiens – A Brief History of Humankind — Yuval Noah Harari

- Fortunate Son — John Fogerty

- The Cobra — Frederick Forsyth (re-read)

Rita Rodgers

- The Blue Moth of Morning — Poems by P.C. Vandall (Rita’s friend)

- If It Bleeds — Stephen King

- The Goldfinch — Donna Tartt

- Eleanor Oliphant is Completely Fine — Gail Honeyman

- The Alice Network — Kate Quinn

Emily Rodgers

- The Flames — Leonard Cohen

- The Story of the Human Body — Daniel E. Lieberman

- Saints for All Seasons — John J. Delaney

- Ten Poems for Difficult Times — Roger Housden

- The Bible

Alan Rodgers

- The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People — Stephen R. Covey

- How to Win Friends and Influence People — Dale Carnegie

- The Daily Stoic — Ryan Holiday

- Rogue Trader — Andy Hoare

- Johnathan Strange & Mr. Norrell — Susanna Clarke

That’s the Rodgers reads. What about you Kill Zoners? Let’s read what TKZ contributors and followers have on the nightstands. Go ahead and list five books you’ve recently read, are now reading, or have on the TBR list. That includes paper, digital, or however you like to read.

———

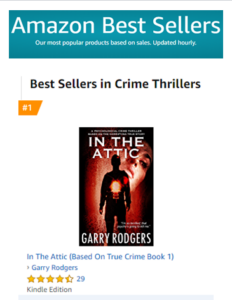

Garry Rodgers is a retired murder cop with a second career as a guy no one wanted an appointment with — Dr. Death, the coroner. Now Garry passes himself off as an indie crime writer who checks his Amazon sales stats every half hour.

Garry Rodgers is a retired murder cop with a second career as a guy no one wanted an appointment with — Dr. Death, the coroner. Now Garry passes himself off as an indie crime writer who checks his Amazon sales stats every half hour.

Speaking of crime writing, Garry Rodgers has six books out in a twelve part Based-On-True-Crime series. Garry’s first one, In The Attic, is available for FREE on Amazon, Kobo, and Nook. Help yourself to one for the holidays!

What A Difference A Quarter Century Makes

My first novel, Nathan’s Run, first hit the shelves in 1996–two millennia ago in book-time. To put it in perspective, Bantam, Doubleday and Dell were all different publishers back then. Simon & Schuster and HarperCollins were independent companies. Back then, the big money came to authors via mass market paperback deals because jobbers filled book racks in every pharmacy and grocery store, and everybody read paperbacks. Mass market rights often were sold to different publishers than the hard cover houses, and for much more money.

Borders Books and Barnes and Noble were just beginning to spread their wings, targeting local bookstores with extreme prejudice. In the mid-nineties, independent bookstores were the backbone of book sales. Every strip mall, it seemed, had its own bookstore. Some were generalists, selling all kinds of books, but others were specialty stores, targeting specific genres. Mystery bookstores grew like weeds.

When the superstore booksellers entered the scene, they were able to negotiate terms with publishers that allowed them to price books at retail for less than what the independents had to pay for wholesale. When really big books hit the scene, it seemed to me (though I could never prove it) that the superstores waded into predatory pricing, selling the books for less than what they paid as loss leaders that would force the mom and pop shops out of business.

Meanwhile, a guy named Bezos was a laughing stock throughout the publishing world because he had this crazy idea that people would buy books from their computers–no, really, their computers! Have you ever heard something so silly? As if book lovers would give up glorious trips to the local bookstore in favor of shopping on one of those squealy dial-up modem desk toys. At the same time, a kid named Steve Case was toiling like mad to create a platform that would give everyday people access to a thing called the internet.

In the mid-nineties, the competition among publishers to acquire the Next Big Book was cutthroat. Authors and their agents had so many big houses to choose from! And the result often ended in bidding wars or pre-emptive bids that routinely netted six- and seven-figure deals for first-time authors.

Money flowed in torrents. Big producers at major film studios paid real money to interns and assistants in the major publishing houses to steal manuscripts from the copy room to give the studios a leg-up on the inevitable bidding war for film rights. During the Christmas season back in the day, every publishing house threw lavish holiday bashes for their staffs, authors, agents and media.

Hands down, the most jaw-droppingly over-the-top book affair I’ve ever attended was a Christmas party thrown by Readers Digest Condensed Books at the New York Palace Hotel in New York (formerly the Helmsley Palace). Limitless beef, salmon, shrimp, caviar, Champaign, booze and desserts served to every author, editor and agent in the world, it seemed. There had to be a thousand people there, including every author who’d ever had a book included in a collection by RD. As a kid from Virginia whose first book was about to be released, this was heady stuff.

(Teaser: The most opulent party ever was the three-day celebration of Dino DeLaurentiis’s birthday on the Island of Capri. That was beyond amazing, and a very funny story. Maybe in a future post.)

Within a few years, everything changed. I don’t remember the order in which they fell, but over the course of what felt like a few months, overseas corporations consumed dozens of imprints and the number of “Big Houses” started to contract. The contraction never stopped. The recent news of Penguin Random’s purchase of Simon & Schuster saddens me. All I see are diminishing opportunities for writers earn big advances for their books. Think about it. Penguin Random (a part of the Bertelsmann empire) has assimilated once-grand independent publisher names such as Penguin, Random House (duh), Bantam, Doubleday, Dell, Viking, Knopf, and others. And it doesn’t stop with the the Bertelsmann empire. Hachette is another, and there are still more.

Meanwhile, Karma being a be-otch, Borders Books is dead, and B&N is moribund at best. (In a happy bit of irony, B&N’s new CEO, James Daunt, is designing the company’s phoenix-like rise from its ashes on the direct involvement of on-the-ground booksellers in the decisions on what books individual stores should stock. You know, the way booksellers used to do it before the superstores ran them out of business.)

Independent bookstores are making a comeback (albeit very slowly and cautiously), and new publishing houses are being born every day.

While the bookracks in drug stores are gone, more books are published every year nowadays than have ever been published before. Ebooks, audio, graphic novels, and Lord only knows how many other new avenues for storytelling are exploding. While all these options bring limitless opportunity, they also bring limitless problems, not the least of which is discovering the new metrics and strategies for letting readers know that a new author has arrived on the scene. Those full-page ads in major dailies that used to grease the skids to bestsellerdom, are all but irrelevant now. Word of mouth has morphed into tweet-to-tweet (or something like that).

These are exciting times to be an author. But they’re also scary times. Million-dollar advances have gone the way of the dodo (or of Borders Books) and that’s probably a good thing in the long run. It makes a lot of sense to align advances with anticipated sales. Hollywood is an evolving train wreck, but it will straighten itself out, too. I’d hate to own a theater chain right now, but man oh man would I like to invest in big screen televisions for the home market.

As I write this post, it occurs to me that as the business fluctuates and expands and contracts, the one constant to all of it, through all of time, is the public’s insatiable desire for good stories, well told. And that, TKZ family, is where we come in. If we don’t think this stuff up and put it on paper, the whole of the entertainment business breaks down.

I’d love to hear any thoughts you might have.

Finally, this is it for me here in The Killzone for a few weeks as we take our winter hiatus. Thank you all for making this blog what it has become. Contributors, you force the rest of us to keep the bar high. Readers, you’re the reason we do it, and your numbers speak for themselves. Thank you. I wish you all a wonderful holiday season, and a prosperous, healthy and happy new year.

God bless us, every one.

The “Last” First Page Critique:

It’s A Jungle Out There

By PJ Parrish

This is my last post of the year before we take our annual holiday break. That means I have an excuse to post a picture of my dogs. Merry Christmas from Phoebe and Archie! Woof.

It also means I have the pleasure of reading my final First Page Critique of 2020, and offering it up to the TKZ hive for comments. It’s a medical thriller, and we’re off to the jungles of Jakarta. The plane is on the runway. Catch you on the return trip, crime dogs.

The Lazarus Outbreak

Republic of Nanga Selak, 650km Northwest of Jakarta

The scientists were late for their pickup.

Danni Lachlan swore and checked her watch again. She paced back and forth while staying in the shadow cast by her Cessna. The nose of the twin-engine plane pointed resolutely down the ribbon of dirt that barely qualified as a takeoff and landing strip.

Palm-leafed trees and vines dotted with colorful orchids still clung to the edges of the recently cleared space. Smells of rotting vegetation and jungle flowers hung in the air. The odd mix of scents reminded Lachlan of a perfumed burial shroud.

A shiver ran down her spine at the thought.

“Never should’ve taken this damn job,” she muttered under her breath.

She dug into a pocket before coming up with a cigarette and a lighter. She took a moment to light up before drawing breath and exhaling a cloud of smoke. The nicotine habit and the bush pilot company were all her ex-husband had left her. She’d made the best of both to keep sane and put food on the table.

Lachlan’s head jerked up as she heard a cry.

It could’ve been a human cry, but the jungle had a hundred ways of distorting sound. Her pulse started to pound as something made a loud rustle.

Suddenly, three people in silvery protective clothing tore free of the underbrush. The name CLARK had been stenciled in black across the chest of one, WIJAYA on another. The silver-suited one in the middle hung limply in the arms of the other two. The name HAYES was barely visible as the other two dragged their companion along.

A demented howl erupted from the tree line. Then a flicker of movement came from the bushes nearby. Clark and Wijaya traded a glance.

They dropped Hayes in the dirt and ran towards the plane.

“What is it?” Lachlan shouted. “What’s going on?”

The two scientists tore off their respirator masks and tossed them away as they ran. Wijaya’s coppery face stared blankly in fear. Clark’s was a mirror image in pale white.

“Start the plane!” Clark cried. “Get us out of here!”

Lachlan stared a moment longer.

Hayes’ body lay face down. It began to quiver. Arms and legs drummed mindlessly against the moist earth.

More flickers of moment in the underbrush. The sounds of something tearing its way through the underbrush. That finally broke Lachlan’s horrified stare and got her moving.

_________________

Let’s start with what works. We’re at a good dramatic moment, which is often a great entry point for a story. (Caveat: You needn’t always start with something this “action” oriented. A dramatic movement can be more subtle). The writer chose a good moment, just before the proverbial $%&^ hits the propellers.

I like how we get just the barest snippet of backstory — that she’s got a bad marriage behind her that makes her a bit bitter. I don’t mind that at all…it intrigues me, character-wise. Notice that the writer did not feel compelled to belabor Danni’s past or state of mind. Get the plot moving first! You can always layer in her past in “quiet” moments later.

A note: The writer could have opened right with the sound of the men breaking through the brush dragging their comrade toward the plane. That’s certainly more action-y. But I like the fact we get to “meet” the heroine first, as she waits for the rendezvous.

I like the location. Never been to Jakarta (closest I got to a jungle was my backyard in South Florida). The atmosphere and sense of isolation is nicely rendered. Good uses of senses beyond sight. Smell is oft-neglected in description. Wondering how the air feels, though. Like standing in a sauna, I would guess. Maybe she’s feel the press of her sweat-damp shirt? Brush away a wet strand of hair? The writer makes a point of saying Danni is pacing in the “shadow of her Cessna.” Good detail but it can be sharper by making the point that it’s the only shade from the searing sun?

Description is important, especially if you’re using a foreign locale. Don’t let any chance slip by to make us feel we are there. Description, used well, can enhance the sense of peril, fear, anticipation (whatever mood you’re going for). But keep it razor-sharp, never over-wrought or too long in the early pages.

The writer is in firm grasp of basic craft, like dialogue, action choreography. We can tell pretty much what is happening here, so kudos there.

Something that confuses me. Danni is waiting for a team of scientists, as stated in the first sentence. Is she part of the team? Is she merely a pilot and thus doesn’t know them? Might want to drop in a clarifying hint. (See comments below about increasing tension)

About that first sentence. The writer sets it off all by itself in its own graph. When you do that, you’re telling the reader it is extra important. Yet the sentence itself is sort of flat and matter-of-fact. Like: “Well, damn, they’re late, so here I am again just cooling my heels.” It lacks enough drama to set up what happens next. Especially since you make a big point of Danni’s impatience. Why is she pacing? Does she know there is danger in getting this team out? The word “pick up” is just sort of blah as well. Because we don’t know Danni’s exact role here, we can’t get the full effect of the urgency you’re trying to create with this scene.

I don’t know what might work better (ideas welcome!), but I think, given the excitement of this opening scene, you can come up with a better first line.

Let’s do a quick line edit so I can bring up some other points. My comments in red.

The Lazarus Outbreak The title works fine for a medical thriller. Even if you don’t know your Bible, that Lazarus rose from the dead, it’s interesting. I just hope the use of the biblical reference ties into the plot. Like, if you’re infected, you die then are reborn ie zombies?

Republic of Nanga Selak, 650km Northwest of Jakarta I’m not a big fan of location tags but this one is okay because the action comes on so quickly, the writer doesn’t have an easy way to tell us where we are.

The scientists were late for their pickup. As I said in comments, this is too blah for this good of a scene. You’d be better off just cutting it and opening with the second graph and finding a way to slip in the “scientists” info. Maybe something like:

Danni Lachlan swore and checked her watch again. She paced back and forth, careful to stay in the shadow of her Cessna, the only relief from the blazing sun. She looked down the ribbon of dirt in front of the plane, wondering again if there was enough room to take off. The landing had been hard enough.

She came out of the shade and brought up a hand to shield her eyes as she peered into the dense jungle just ten yards away.

Where the hell were they? They knew they had only a half-hour window to get out of here.

A sharp crack made her spin to the other side of the brush.

Two men in silver hazmat suits stumbled into the open, dragging a man between them.

Danni Lachlan swore and checked her watch again. She paced, back and forth while staying in the shadow cast by of her Cessna. The nose of the twin-engine plane pointed resolutely means admirably purposeful; too human for a machine and clutters things up. down the ribbon of dirt that barely qualified as a takeoff and landing strip. Do more with this image; ie she had barely made the landing…

Palm-leafed trees and vines dotted with colorful orchids still clung to the edges of the recently cleared space. This implies knowledge on her part, so she has been here before? Or is she a team member? Clarify if you use it. ALSO: how far away is the brush from the plane? We need to know to understand the action when the scientists come running out. Smells of rotting vegetation and jungle flowers hung in the air. The odd mix of scents reminded Lachlan of a burial shroud. Again, I love that you use smells here, but can you make this sing more, be specific? The still heavy air smelled of rotting vegetation and jasmine. (I checked; it’s common in Jakarta). The mixture reminded Lachlan of a burial shroud. I don’t think this works. It sounds like YOU the WRITER describing something, not your character. Would this woman think in those images? Not unless it is in her specific sensory bank of memories. ALWAYS KEEP COMPARISONS, METAPHORS, SIMILES specific to your character’s experience. It feels more real and it helps you establish character traits. I can’t say what smell in her memory comes to her; that is for you to decide, but it has to connect to HER.

A shiver ran down her spine a cliche at the thought. BUT…if that awful smell you describe above made her shiver then that means it RESONATES with something in her past. What in her memory made her shiver at that smell? It wasn’t a burial shroud, as they aren’t common anymore.

“Never should’ve taken this damn job,” she muttered under her breath. I like this line here.

She dug into a pocket for before coming up with a cigarette and a lighter. She lit up and pulled in a quick deep breath. took a moment to light up before drawing breath and exhaling a cloud of smoke. Don’t waste words on routine actions. The nicotine habit and the bush pilot company were all her ex-husband had left her. Good! She’d made the best of both to keep sane and put food on the table.

Lachlan’s head jerked up as she heard a cry. The cry comes first, then her reaction.

It could’ve been a human cry, but the jungle had a hundred ways of distorting sound. Her pulse started to pound as something made a loud rustle. Again, action causes her reaction. Also gives you a way to get rid of the clumsy “as.” You overuse the “as” construction.

Suddenly, three people in silvery protective clothing I think she’d recognize hazmat suits and you have to put the fact they are wearing masks HERE not later because that is what she would notice first. And a note about breathing masks: They are in a jungle, it’s as hot as hell and these guys are in MASKS? What might she think? Use this moment to increase tension. SOMETHING ISN’T RIGHT HERE. EXPLOIT THAT. tore free of the underbrush. The name CLARK had been stenciled in black across the chest of one, WIJAYA on another. The silver-suited one in the middle hung limply in the arms of the other two. The name HAYES was barely visible as the other two dragged their companion along. This is important: When choreographing action, you must keep the order of the character’s recognition logical. What would Danni notice first? Names? Nope. She’d notice the men struggling to drag the third guy. If they are dragging a man, who’s apparently dying, they’d be crouched over; impossible to see their names. Plus, is it important to name them right now? Does she know them? If not, why bother?

A demented howl Not sure demented works here. It means angry or crazyerupted from the tree line. Then a flicker of movement came from the bushes nearby. Refract this through her POV somehow. Danni saw the fronds on the low palms behind the three men moving.

Clark and Wijaya traded a glance. Too casual sounding. Stay in action phrasing.

The two men heard it, too. They looked back at the jungle then at each other. They dropped the third man and ran toward the plane.

They dropped Hayes in the dirt and ran towards the plane.

“What is it?” Lachlan shouted. “What’s going on?”

This stretch of action implies they have a lot space to cover, yet you said the “runway” was a narrow ribbon carved from the jungle. Clarify this. The two scientists men tore off their respirator masks and tossed them away as they ran. Wijaya’s coppery face stared blankly in fear. Clark’s was a mirror image in pale white. This could use some work. Coppery face? Is he foreign? And he’s running for his life so I don’t think he’d have a blank stare. At this point the name CLARK on his suit might register in her consciousness but ONLY at this late point. Which might be where you to drop in the plot point that she’s ferrying out scientists. Waiting to tell the reader until now that they are scientists is a way to increase intrigue…dole out your plot one bread crumb at a time. Sometimes you want to hold facts back to make more impact later. It all about layering…

His dark face was contorted with fear. She saw the name CLARK stenciled across the front of his suit. Clark…Duane Clark, one of the three scientists she had been hired to fly out here.

“Start the plane!” Clark cried. “Get us out of here!”

Lachlan stared a moment longer. At what? Where is the second man? Again, keep her impressions of the action in a logical order. They dropped the third guy so she can’t possibly see his name. Something simple like:

The second man stumbled to the Cessna, but Lachlan’s eyes were locked on the man they had abandoned. He lay twenty feet away, face down in the dirt. His body was quivering, arms and legs drumming in the red dirt.

Hayes’ body lay face down. It began to quiver. Arms and legs drummed mindlessly against the moist earth.

More flickers of moment in the underbrush. The sounds of something tearing its way through the underbrush. That finally broke Lachlan’s horrified stare and got her moving. I think we’ve got too many “flickers” in the brush. Maybe save the howl for here so you get a fresh punch. And make it really awful. Then don’t TELL me she gets moving. SHOW me her moving.

Danni jerked open the door of the Cessna. Clark half-carried the second men the final yard to the plane and together they pushed him inside. Jumping into the pilot seat, she pushed the throttle in and hit the master switch. The Cessna roared to life, drowning out the sound of…WHATEVER THAT AWFUL HOWL WAS.

So, this is what I would call a good first draft. Nice action, an exotic location, an interesting protag. (assuming Danni is such) and lots of juicy unanswered questions. Don’t be discouraged by my bleeding red all over your pages, dear writer. As I said, this is good stuff and we all find ways to improve as we go through various rewrites. Mine is just one opinion.

Thank you, anon writer, for letting us share your work. I know how hard this is, to put your baby out there for scrutiny. I’ve had some tough editors over the years, and it took me a while to realize they were tough because they wanted me to succeed. We’re here for you.

Merry Christmas, Happy Hanukkah, all, and may the next year be…well, let’s just say brighter, healthier and a helluva lot more huggable.

On Using Humor in Fiction

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

I received the following email the other day, and present it here with the sender’s permission.

I received the following email the other day, and present it here with the sender’s permission.

Dear Mr. Bell,

Your Great Courses lectures on writing best-selling fiction are packed with helpful information, and because of them I’m now making progress with my fiction-writing. But I struggle with humor, since I am not naturally funny. I rarely come out with anything that makes people laugh, and when I do, it’s usually accidental.

I’ve begun reading Try Fear, and am impressed by how masterfully you inject humor into your fiction. Would you recommend a resource for learning to write humor?

I’m a children’s writer, with a couple of non-fiction articles and one book for the educational market to my credit, but I’ve caught the fiction bug and am attempting the leap from nonfiction to fiction. I’d be grateful for any suggestions you have on learning to write humor.

Great question, and one I don’t remember addressing before.

Let’s first distinguish between two types of book-length fiction: the humorous novel and the novel with humor. In the former case, the whole enterprise is based on getting laughs. Douglas Adams’ The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy is a prime example. In the latter type of novel, humor is used for what the dramatists call “comic relief.” Shakespeare employed this device frequently, most famously with the gravediggers in Hamlet.

Let’s first distinguish between two types of book-length fiction: the humorous novel and the novel with humor. In the former case, the whole enterprise is based on getting laughs. Douglas Adams’ The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy is a prime example. In the latter type of novel, humor is used for what the dramatists call “comic relief.” Shakespeare employed this device frequently, most famously with the gravediggers in Hamlet.

As to the first type, I don’t have anything to offer, except: proceed with caution. It takes a rare talent—like a Douglas Adams or a Carl Hiaasen—to succeed with this kind of novel. Also note that comic novels don’t sell much as compared to their more serious cousins. Early in his career Dean Koontz tried his hand at a humorous novel, a la Catch-22, and determined this was not a genre that paid. Since going serious, with humor sprinkled it, Mr. Koontz has made a few bucks.

So let’s talk about humor used on occasion in an otherwise serious novel. Why have it at all? Comic relief, as the name implies, is a spot within the suspense where the audience can catch its breath. It delivers a slight respite before resuming the tension. It’s sort of like the pause at the top of a roller-coaster. You take in a breath, look at the nice view and then…BOOM! Off you go again. It adds a pleasing, emotional crosscurrent to the fictive dream, which is what readers are paying for, after all.

I see three main ways to weave humor into a novel: situational, descriptive, and conversational.

Situational

You can insert a scene, or a long beat within a scene, that takes its comic effect from the situation the character finds himself in. For an example I turn to the great Alfred Hitchcock, who almost always has comic relief in his masterpieces of suspense.

Like the auction scene in North by Northwest. Roger Thornhill (Cary Grant) has been mistakenly tagged as a U.S. secret agent by a group of bad guys. At one point, Thornhill walks into a fancy art auction to confront the chief bad guy (James Mason). But now he’s stuck there with three deadly henchmen waiting in the wings to send him to the eternal dirt nap.

So Thornhill hatches a plan. Act like a nut and cause a commotion so the cops will come in and arrest him, saving him from the assassins. This is how it goes down:

How do you find situational humor? You look at a scene and the circumstances and push beyond what is expected. Most humor is based upon the unexpected. That’s what makes for the punch line in a joke, for example. So make a list of possible unexpected actions your character might take or encounter, and surely one of them will be the seed of comic relief.

Descriptive

When you are writing in First Person POV, the voice of the narrator can drop in a bit of humor when describing a setting or another character. The master of colorful description was, of course, Raymond Chandler, through the voice of his detective, Philip Marlowe:

It must have been Friday because the fish smell from the Mansion House coffee-shop next door was strong enough to build a garage on. (“Bay City Blues)

From thirty feet away she looked like a lot of class. From ten feet away she looked like something made up to be seen from thirty feet away. (The High Window)

It was a blonde. A blonde to make a bishop kick a hole in a stained-glass window. (Farewell, My Lovely)

The girl gave him a look which ought to have stuck at least four inches out of his back. (The Long Goodbye)

For descriptive humor, listen to your character. Use a voice journal to let the character riff for awhile. You’ll unearth a nugget or two of descriptive gold.

Conversational

Dialogue presents many possibilities for humor. First, you can create characters who have the potential for funny talk. Second, you can take create conversational situations where such talk is possible. I had two great aunts who lived together in their later years. They had a way of subtly sniping at each other over minor matters, which was always a source of amusement to me. So I put them in my thriller, Long Lost, as two volunteers at a small hospital:

Just inside the front doors, two elderly women sat at a reception desk. They were dressed in blue smocks with yellow tags identifying them as volunteers. One of them had slate-colored hair done up in curls. The other had dyed hers a shade of red that did not exist in nature.

They looked surprised and delighted when Steve came in, as if he were the Pony Express riding into the fort.

They fought for the first word. Curls said, “May I help—” at the same time Red said, “Who are you here to—”

They stopped and looked at each other, half-annoyed, half-amused, then back at Steve.

And spoke over each other again.

“Let me help you out,” Steve said. “I’m looking for a doctor, a certain—”

“Are you hurt?” Curls said.

“Our emergency entrance is around to the side,” Red said.

“No, I—”

“Oh, but we just had a shooting,” Curls said.

“A stinking old man,” Red added.

“Not stinking,” Curls said. “Stinko. He was drunk.”

“When you’re drunk you can stink, too,” Red said.

“That’s hardly the point,” Curls said.

And it goes on like that.

I think you can develop an ear for this kind of humor by soaking in the masters of verbal comedy. Start with Marx Brothers, especially their five best movies: The Coconuts, Animal Crackers, Monkey Business, Horse Feathers, Duck Soup.

Listen to the classic conversational routines of Bob Newhart (available on YouTube). My favorite is “The Driving Instructor.”

Also on YouTube: Bob & Ray. The great thing about their skits is how they play them with dead seriousness. That’s where the humor comes from, which is a lesson for writers. This isn’t about jokes. It’s about natural humor found in a fully developed dramatic situation.

If you want to do some reading on the subject, you might pick up a copy of Steve Allen’s How to Be Funny. Allen was one of the great verbal wits.

There’s also a little gem of a book on writing comedy. It’s the nearly-lost wisdom of Danny Simon, Neil’s older brother (whom Neil and Woody Allen both credit with teaching them how to write narrative comedy). Danny Simon never wrote a book on the subject. He did teach a famous comedy writing class in Los Angeles. Thankfully, one of his students took copious notes and organized them for posterity. That student was me, and the little book is here.

The floor is now open for discussion on these matters. Meanwhile, I can’t resist leaving you with my all-time favorite Bob & Ray routine. Enjoy!

Getting Through It

Source: passionatepennypincher.com

I have been working on a couple of different posts to offer as my last for this year. One has the working title of “Prepping for the Zombie Apocalypse at Dollar Tree.” The other is tentatively named “The Two Best Books That I Will Probably Never Read. Neither Will Anyone Else.” You may see one or both of those next year. What happened in the here and now was that the rubber was meeting the road as far as decide-and-finish was concerned when I came across the chart that you will see above. Something told me that it was more important to share it than the bits of wisdom and whimsy that I had planned. Things blossomed from there and it was off to the races.

It was and is a part of my program for embracing the suck that is 2020. The military term “embrace the suck” can be distilled to a simple admonition. That would be best described as acknowledging that a situation is bad and dealing with it, going over it, around it, or through it. That’s a bit of an oversimplification but close enough for rock ‘n’ roll.

2020 will not go down as a wonderful year. It thus gave us, each of us, a wonderful opportunity. It gave us the chance to embrace the suck. I don’t know anyone personally who died of COVID-19 but I do know several people who contracted it and many, many more who thought they had it and did not but were sick with something else. Virtually everyone I know experienced some adverse secondary reaction as a result of it. Let me count the ways. Isolation. Diminished income. Loss of jobs. Domestic problems. Each of them continued to get up every morning and did what they needed to do, went to bed, got up the next morning, and did it all again. They embraced the suck. I daresay that if you got up today and are reading this then you are doing the same thing. Woody Allen is credited with observing that ninety percent of everything is showing up. You showed up. You zoomed meetings and read and wrote and worked and shopped and made meals and probably helped others at some point. The sun came up every morning and so did you. Good on you.

I have mentioned the late Miles Davis a number of times in this spot. Miles was a complicated personality who often got in his own way but he was an immense talent whose music still sounds groundbreaking and in some cases ahead of his time three decades after his death. His music wasn’t formulaic but he had a formula, which was “Play what you know, and play above that.”

That statement is applicable to life in general, and particularly life right now. For writing, it’s everything. Aim to write the best that you can every day, and write above that. It’s true of life, too. Live as best as you can, and then strive to live to do better. You’ll fail frequently, but you’ll succeed too.

That brings me to the chart above which comes from the good folks at passionatepennypincher.com. I don’t reflexively think of food banks during the year, but every December our local one has a food drive. Their goal for this year’s drive — again, a tough year for everyone — on December 5 was to collect thirty thousand pounds of food. They collected sixty thousand pounds. In one day. A bag at a time. If you are inclined and you are financially or physically able to do so that reverse Advent chart above is a great guide to what you can do to do live as best as you can, and maybe a bit above. Or you can help someone out, be it a stranger or a neighbor, in some other way. It doesn’t have to involve a transaction. It can be as simple as an effort to give someone an extra smile or a hello or an assist. You can communicate a smile through a mask, by the way. It’s surprising but true. Even I, who really, really does not care much for people as a group, can do it.

Oh, yeah. The Humane Society. They take care of my favorite people. If you like animals but can’t have a pet most humane societies are begging for folks to come in and interact with the animals there. I can’t do it. The last time I did I had a meltdown because I couldn’t take them all home. I contribute in other ways instead. One does what one can. Please.

Bottom line: be well, and embrace it all. Own it and conquer it. Write, read, watch, be good to yourself first, and then someone/something else. Be happy amid the noise and waste.

Chag Urim Sameach, Merry Christmas in two weeks, and Happy New Year in three. I will see you back here on January 9. Thanks as always for being here.

Writers in Waiting

In the writing business, there’s one thing we all have in common – waiting.

I’m not sure if waiting should be classed as an art or a skill, but it’s something we writers endure. It’s our common bond. All writers, indie or traditionally published, beginners or old hands, are waiting for something.

We’re waiting for our manuscript to be accepted.

We’re waiting for our editor to read our next novel.

We’re waiting for the copy-edits to be finished.

We’re waiting for the page proofs.

We’re waiting for our agent to tell us what she thinks of our proposal.

We’re waiting to see how that new mystery we just released online sells.

We’re waiting to see the new cover the artist promised by Friday.

We’re waiting to see if our short story will be accepted in the new anthology.

We’re waiting for a contract.

We’re waiting to see if we won that contest for unpublished writers.

We’re waiting for a royalty check. (Oh, yeah, that one.)

Some of us are better at waiting than others. When I’m waiting, I’m like an old-school teenager waiting for a phone call from the coolest guy at school – I jump every time the phone rings, and nearly kill myself answering it. I’m afraid to leave the house, and when I do leave, I hurry back. I check messages every ten seconds. I bug Don, my long-suffering spouse, with questions he can’t answer: Do you think he’ll call today? If he does, will he buy it? If he buys it, do you think it will sell?

Some of us are better at waiting than others. When I’m waiting, I’m like an old-school teenager waiting for a phone call from the coolest guy at school – I jump every time the phone rings, and nearly kill myself answering it. I’m afraid to leave the house, and when I do leave, I hurry back. I check messages every ten seconds. I bug Don, my long-suffering spouse, with questions he can’t answer: Do you think he’ll call today? If he does, will he buy it? If he buys it, do you think it will sell?

Meanwhile, Don’s waiting for me to shut up.

I ask myself all the questions that should calm me:

What’s the worst thing that could happen if it doesn’t work?

I can entertain myself for hours with worst-case scenarios: I won’t make any money. I’ll have to start over. I can always sell it elsewhere. I can, can’t I?

Possibly the scariest waiting game I ever played was when I met Genny Ostertag. Genny was a hot new editor at a major New York publisher, back when those existed, and she was going to the Malice Domestic convention at the Crystal Gateway Marriott in Arlington, Virginia. In those days, the hotel was located on Jefferson Davis Highway. That road has since become the Richmond Highway.

Genny and my agent had been playing telephone tag. I waited for days to hear back from him, while chugging Pepto-Bismol. Finally he finally called with the news:

He’d arranged a meeting with Genny. “She wants to have a drink in the bar with you,” he said, “and she wants to talk to you about your proposed series.”

Wow. Visions of fat advances danced in my head.

“But remember,” he said. “You can’t mention it until she says the magic words: ‘What are you working on?’ Before that, you have to make small talk. Promise.”

I promised, though I didn’t realize the wear and tear it would create.

I went to the convention bar half an hour early to meet Genny. I was too scared to drink, so I bribed the bartender to dress up my club soda and make it look like an adult beverage. Genny arrived and ordered white wine. We met and said hello, then made stiff small talk until Genny said, “Can you believe this hotel is on Jefferson Davis Highway? Don’t they know they lost the Civil War?”

And suddenly we were talking about the Civil War. I dredged up every fact I could remember about the Jeff Davis and the Civil War. (Did you know that Jefferson Davis used to be Secretary of War for the USA, and he started the US Camel Corps? Yep, he served under President Franklin Pierce, and that’s about all I know on Pierce. Anyway, Davis believed camels would survive in the deserts of the far West better than horses. His idea might have worked, except the experiment was interrupted by guess what? The Civil War. Just as well. I can’t see John Wayne riding to the rescue on a camel.)

And suddenly we were talking about the Civil War. I dredged up every fact I could remember about the Jeff Davis and the Civil War. (Did you know that Jefferson Davis used to be Secretary of War for the USA, and he started the US Camel Corps? Yep, he served under President Franklin Pierce, and that’s about all I know on Pierce. Anyway, Davis believed camels would survive in the deserts of the far West better than horses. His idea might have worked, except the experiment was interrupted by guess what? The Civil War. Just as well. I can’t see John Wayne riding to the rescue on a camel.)

Our conversation seemed to last at least as long as that war (1861 to 1865, just ask me) until finally, finally, Genny said, “So, what are you working on?”

And I told her about my idea for the Dead-End Job series. Genny became my editor and bought the series, which resulted in fifteen mysteries and a lot of adventures working those dead-end jobs. So it was worth the wait.

What are you waiting for, readers?

*************************************************************************

Don’t wait! Buy the newly released ebook versions of the Dead-End Job mysteries, the Josie Marcus, Mystery Shopper mysteries, and Francesca Vierling mysteries here: https://awfulagent.com/ebooks/?author=elaine-viets

Don’t wait! Buy the newly released ebook versions of the Dead-End Job mysteries, the Josie Marcus, Mystery Shopper mysteries, and Francesca Vierling mysteries here: https://awfulagent.com/ebooks/?author=elaine-viets

Dreams, Goals, and a Gift

Dreams, Goals, and a Gift

Terry Odell

This is my last official post of 2020, but the official TKZ Winter Hiatus doesn’t start until December 21st, so don’t stop visiting.

This is my last official post of 2020, but the official TKZ Winter Hiatus doesn’t start until December 21st, so don’t stop visiting.

Is it too early to think about the New Year? Are you already thinking about the tradition of making resolutions? With a new year come new beginnings. Fresh starts. We all enter a new year filled with hope and promises to make it better than the last one.

And, usually, by the end of January, all those good intentions have gone by the wayside. I gave up making resolutions long ago (although I occasionally make them for the Hubster—less chance of me breaking them that way). What I’ve learned, is that if you want to see success, you have to narrow your focus.

These resolutions don’t work:

- I resolve to be a best-selling author.

- I resolve to write three novels this year.

- I resolve to make $100,000 selling my e-books.

Why don’t they work? They’re dreams.

Dreams are wonderful. Dreams are things you’d love to have, but they’re also things over which you have no control, because they depend on other people. You need goals.

Goals have to be measurable. I learned that way back in college when I was getting my teacher certification. The course was “Behavioral Objectives” and we learned to set ways to measure whether we were getting through to our students. We could set a goal that at least 90% of our students would score at least 80% or better on an exam. This was a measurable outcome. If they didn’t, we’d have to go back and figure out why. And, frankly, the usual answer would be “because I didn’t teach the material effectively”, NOT “the students were lazy slackers.”

Another thing I learned in that course was that you had to take small steps. You had to figure out what skills were required for a student to answer a question on that exam correctly, and then work on practicing those skills. (Not teaching to the test—teaching skills.)

How do you turn those dreams into goals? Break them down into things you can do in small increments, and that you can measure. Being a best-selling author isn’t measurable. (Can I call myself a best-selling author if I pay for an ad and my books hit the number 1 slot on a very small niche at Amazon for a week? Some authors do, but that’s not something I’m comfortable with.)

Those who say, “I’m going to write three books this year” are likely to fail if that’s as far as they go. What does it take to finish the book? You take that lofty goal, break it into small pieces, and then figure out what you can do to achieve each piece.

Write X words/pages a day/week until you’re done. That’s something you can track. You can see your success. You have a specific goal each day/week.

And, most importantly, you can reassess and adjust these goals over the course of the year. Are you making your word count goal by 10 AM? Maybe it’s too low. Are you staying up until 3 AM and still failing? Don’t be afraid to lower it. Of course, you’ll want to take a hard look at why you’re not meeting your word count goals. If it’s because you’re spending 8 hours a day on Facebook, you might want to cut back on your social media time!

As for making $100,000? That’s a dream that depends on others. You have no control over who buys your books. You can develop a marketing plan, a budget, hire a publicist, but the sales are out of your hands. The one thing you can do, however, is to use the best marketing tool out there. Write the next book!

Whatever you’re looking for in the new year, I wish you the best in attaining it.

(Did you forget about the word “Gift” in the title? If you’ve read this far, I’ve got one for you.)

Tomorrow is the first night of Hanukkah, which is the winter holiday my family celebrates, although there’s likely to be a different slant on the retelling of the “miracle” this year.

Tomorrow is the first night of Hanukkah, which is the winter holiday my family celebrates, although there’s likely to be a different slant on the retelling of the “miracle” this year.

Because I consider everyone at TKZ, on both sides of the site, my family, I thought I’d offer you a gift as my last TKZ offering of 2020.

My gift to you: Enjoy a free download of Deadly Production, Book 4 in my Mapleton Mystery series. You can find your gift at Book Funnel. You can download an epub, mobi, or PDF file. If you have trouble, the wonderful folks at BookFunnel will be happy to help. (Download deadline is December 18th.)

My gift to you: Enjoy a free download of Deadly Production, Book 4 in my Mapleton Mystery series. You can find your gift at Book Funnel. You can download an epub, mobi, or PDF file. If you have trouble, the wonderful folks at BookFunnel will be happy to help. (Download deadline is December 18th.)

Have a wonderful and safe holiday season.

My new Mystery Romance, Heather’s Chase, is available at most e-book channels. and and in print from Amazon.

My new Mystery Romance, Heather’s Chase, is available at most e-book channels. and and in print from Amazon.

Terry Odell is an award-winning author of Mystery and Romantic Suspense, although she prefers to think of them all as “Mysteries with Relationships.” Follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

The “Other” Debbie Burke

by Debbie Burke

Debbie Burke is not that unusual a name. But what if there are two Debbie Burkes who are both authors? Hmm.

About a year ago, I googled “Debbie Burke.” As expected, my thrillers, TKZ blog posts, news articles, and website came up.

But I did a double-take when I saw “Debbie Burke” was the author of jazz articles and a novel entitled Glissando.

I hadn’t written any of those.

Dug a little deeper and checked out the other Debbie Burke’s website which is debbieburkeauthor.com. Mine is debbieburkewriter.com. How confusing is that!

I discovered she is from the Poconos and now lives in Virginia Beach, VA.

For simplicity’s sake, from here on, I’ll refer to us at “Montana Debbie Burke (MT DB)” and “Virginia Debbie Burke (VA DB).”

A few months ago, I started to receive odd emails addressed to “Debbie Burke” that I initially thought were spam and deleted. More messages came from someone named Magdalena, who said she had texted me several times and wanted to talk about a jazz award. I realized Magdalena must be trying to reach VA Debbie. I replied that she had contacted the wrong Debbie Burke but I didn’t know an address for VA Debbie.

Then I received an email from “Debbie Burke” and, no, I wasn’t cc’ing myself.

VA Debbie had seen a comment by “Debbie Burke” on the Authors Guild discussion thread that she didn’t write, so she reached out to me. Turns out we’re both AG members. How confusing must that be for AG?

We had a good laugh about the mix-up and struck up a correspondence. Being writers, we inevitably played “What if?”

What if Debbie Burke interviews Debbie Burke?

So, today, here we are.

It’s my pleasure to introduce…Debbie Burke from Virginia.

MT DB: I’ve described how I learned about you. How did you first learn about me?

VA DB: I was setting up my profile in Goodreads and saw that your name popped up with a book…something about the devil…I said hey, that’s not me!

MT DB: Please tell us a little bit about yourself.

VA DB: Born in Brooklyn, now living in Virginia Beach. Most of my career has been in communications, either in printing, publishing, PR, media and so on. I was a columnist for my local paper when we lived in Pennsylvania and I became the editor of a regional business journal there, then the editor of a lifestyle magazine.

My first book came about in 2011 when I joined a community band at a local university, playing sax (I had lessons in at The New School for Social Research in NYC the 1980s. Yes, I’m dating myself).

Anyway, I was in the band and hearing all about these very famous musicians who were said to live nearby. Wow, I thought, I’d love to find out more about the jazz legacy of this area, where can I find a book on that? Surely the local library had something on it. But nobody had written about it. The more I dug, the more I found out about the area’s connections to jazz from the 1920s onward. No book? No problem, I decided to write my own. That was the start of something beautiful. That was The Poconos in B Flat and others have followed. I love writing about jazz.

MT DB: Where can your articles and blog posts be found?

VA DB: My blog (www.debbieburkeauthor.com) is all about the jazz world. I’ve done over 400 interviews of not just musicians but also jazz photographers, artists, record execs, promotions people and authors. I have published some articles that are deep in the archives at All About Jazz and wrote for the Jamey Aebersold blog a while back.

MT DB: Your first novel is Glissando. What inspired you to write it? How did you develop the main character Ellie?

MT DB: Your first novel is Glissando. What inspired you to write it? How did you develop the main character Ellie?

VA DB: Ellie is a composite of a middle-aged woman who’s found that she’s had just about enough of men, period. She joins a university band (that is the only similarity, I promise) where she meets a musician whom she falls very, very hard for. He’s married, and his wife has just graduated from college. A whole lot of drama ensues and Ellie has to make some tough choices about the musician and another man she’s become involved with.

I was inspired, I am inspired, by the dating (mis)adventures of women my age. The difficulties of finding somebody good, the idea of falling in love and in lust when you’re past your mid-point. It’s fascinating to me. I like to write strong women who are more than a little flawed. I don’t agree with all the things Ellie does in the book, but she sure feels real to me.

MT DB: You’re working your second novel. Care to share details?

VA DB: Sure! It’s about a stolen song, a stolen kiss and a stunning family legacy. A jazz bassist finds out his ancestor was enslaved on one of the biggest plantations in Georgia, and miraculously comes across a song that he had written. A shocking secret bubbles up and he embarks on a journey to face it and make things right.

MT DB: You also collaborated on a book that was published in the UK about under-representation of women in the field of jazz. What was that experience like?

MT DB: You also collaborated on a book that was published in the UK about under-representation of women in the field of jazz. What was that experience like?

VA DB: Yes, Gender Disparity in UK Jazz – A Discussion. The experience was amazing times two. Sammy Stein is the consummate interviewer and knows the UK jazz scene with an enviable thoroughness. She’s a great writer and has excellent contacts who made the content very honest and accessible.

I needed to deal first with the logistics of the language itself; avoiding the instinct to “correct” certain words that are spelled differently in the UK than in the US, and the same goes for idioms and expressions of speech. The other major task was creating it and developmentally editing it as we went along. I think we hit all the right notes, if you pardon the pun. Within three days of uploading it to Amazon, it made number 6 in the very competitive category of “Jazz Books.”

MT DB: What is your main strength as a writer?

VA DB: Hearing my characters’ voices telling me the story.

MT DB: What quality as a writer do you need to work on?

VA DB: I’m a “pantser” – no outline in my fiction, writing by the seat of my pants. Well, I’ve come to find out the hard way that the more story threads you have, the more challenging this is. Actually, for me right now as I finish my WIP, it’s hellish. Though I feel like an outline could be suffocating, one guy I watch on YouTube (Michael LaRonn) made a great suggestion in one of his videos, which is to make the outline as you go. So it’s a roadmap that’s informed by your ongoing experiences of writing, not something that had been imposed on you before you knew how the book was going to unfurl.

MT DB: You recently started an editing business. What prompted you to hang out an editing shingle? What type of editing do you offer?

VA DB: I’ve been doing this for many years, and just decided to formalize it with Queen Esther Publishing LLC. It’s one of the most exciting things I’ve ever done, but also very intimidating. Being organized is the key. I have an idea of what I’ll work on each day, and even if everything doesn’t pan out exactly, I’ve stuck to it with broad strokes.

The editing I do – book manuscripts, professional articles, theses, and anything else really – goes all the way from proofing to line edits to developmental editing. I also coach authors in self-publishing and building an author platform.

MT DB: Any other information you’d like to add?

VA DB: It was so nice to “meet” you and read some of your books. I had no idea how you wrote or what you wrote about and was hoping I wouldn’t have to change my name! I’m kidding of course, but I’m sure you felt the same relief. If somebody were to mix us up and look for our books on Amazon, they’d be in for a treat, regardless of which Debbie they got.

MT DB: I couldn’t agree more!

On Twitter: @jazzauthor

On Instagram: @jazzauthor

On Facebook: debbieburkejazzauthor

Blog: www.debbieburkeauthor.com

Editing Services: www.queenestherpublishing.com

~~~

Recently VA Debbie posted her interview with me on her blog. If you’d like to read it, here’s the link: https://bit.ly/DebbieBurkethrillerwriter

~~~

To paraphrase P.T. Barnum: “Say anything about us as long as you spell our name right.”

That’s D-E-B-B-I-E B-U-R-K-E!

~~~

Holiday note: Today is my last post for 2020 before the annual two-week break. Warmest wishes to the TKZ family for happy holidays. May you share this season with loved ones and enjoy it in good health! See you in 2021.

~~~

TKZers: Do you have a “name twin,” or “alter ego,” or “doppelganger”?

~~~

Please check out Tawny Lindholm Thrillers by the Debbie Burke from Montana.