11:00 am

You’ve never been great at fractions, but neither is the NOLA-25 virus. It allegedly kills 1 in 3 people, so why did it wipe out the entire Perez family? That’s six people dead when it’s only supposed to be two. And what about your own family? What’s 1/3 of five? Will the virus kill Marco? That’s only 1 in 5. Marco and Mom? That’s too many. Anyone is one to many. And this virus sucks at math.

Outside your front window, the Perez home at the end of the street is eaten by flames. You used to go to school with Savannah Perez, back when there was in-person school. Now, you’ll never see her again. Yesterday it was Mrs. Mitchell, who lived right behind you. Today it’s the Perez family. That’s just how it goes. A blue van shows up one day without warning and takes the family away. Most of the time they aren’t even feeling any symptoms yet. Soon, a burn notice shows up on their front door and the Fire Squad comes to destroy everything they’ve ever touched. Clothes, furniture, pictures, germs. Only in rare cases does a blue van ever bring a family back home. Exposure to NOLA-25 almost always results in infection, and infection is an almost certain death sentence.

* * *

Your eyes drift over to Marco, riding his bike up and down the block. You feel a twinge of guilt for thinking of him first when fears of the virus creep into your mind. It’s not like you’d choose him to be the one infected. He’s a good big brother (as far as big brothers go). Besides, Marco will be fine — his mask and face shield are on, he stays on your own block. You watch him anyway, just in case someone gets close to him. But there’s no one outside.

Behind you, two women on a morning news program joke about the appearance of a smoothie they’re pouring from a blender. It’s supposed to help boost immunity, but no one could possibly believe a smoothie can stop NOLA-25. As the women jabber on, holding their noses to sip the green concoction, a list of yesterday’s pandemic victims scrolls down the right side of the TV screen. The list includes dozens of names, and those are just the ones in Miami-Dade County. Broward County will be next, with Mrs. Mitchell’s name on the list. Tomorrow, the name Savannah Perez will appear.

Overall comments:

I definitely think this page has potential – there are a few stumbling blocks but none that can’t be overcome – and this definitely feels like an authentic YA voice which can be tricky to achieve! Bravo! For me the main stumbling blocks are:

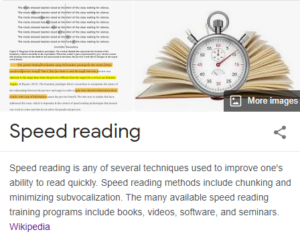

- The use of 2nd person – this is very hard to pull off and while I like the narrator addressing the reader in this way, I’m still not entirely sure this is a sustainable POV for a whole novel. I might get my fellow TKZers to weigh in on this but I think 2nd person is going to be a challenging choice.

- Present tense – although this is very common in YA novels I still think present tense can be off-putting to some readers. While it gives a great sense of immediacy and dramatic tension (The Hunger Games is a great example of successful use of the present tense), it can sound clunky. Although I wouldn’t say don’t use the present tense, I would just caution that it takes a very skilled writer to pull it off effectively.

- Pandemic fatigue – I am torn on this…but I suspect many editors are going to nix a lot of books that deal with a pandemic simply because they are living through one! Again, I’d like my fellow TKZers to weigh in on this, but I am worried that editors will be inundated with pandemic novels (particularly YA). To stand out in this crowd is going to be a challenge and I fear editors are going to be very cautious about acquiring these kind of novels.

None of these stumbling blocks are in any way deal-breakers. They simply present challenges for even a seasoned/experienced writer. There are also some other more specific comments that I’ve listed below – all of which, again, can be easily overcome. Overall, I do see potential in the voice in this first page.

Other specific comments:

Consistency – I was a little confused – in the first paragraph it says that the virus allegedly kills 1 in 3 people but then it says that infection is an almost certain death sentence…which doesn’t totally make sense (I guess I would think killing 2 out of 3 people would be an almost certain death sentence…). It’s also not entirely clear to the reader why the whole house and all the possessions have to be burned even when the family taken away is asymptomatic. I think I need more detailed, consistent information when it comes to the NOLA-25 virus especially as my reading experience is informed by our current pandemic. For instance, is it a respiratory illness (sounds like it as Marco wears a face mask and shield)? How is it spread? (sounds like if they torch everything it spreads on every kind of surface but cannot be disinfected?) How do people know they have been exposed or have the illness if they don’t have any symptoms (or are they just hauled away because the government knows even if they don’t?). When writing a novel about a pandemic, especially given everyone’s heightened awareness, I think you have to be extremely specific with details right from the start for it to feel believable.

Action – This first page is really all exposition – which isn’t a deal breaker either, but I think I would have liked to actually seen real live action – like the blue van coming to take the Perez family away and then the house going up in flames. While reading this, I craved immediate action – I wanted to be in the thick of it, feeling the terror of what is happening, especially given this page is in present tense. I would be far more interested in the Perez family’s experience than the smoothie-making scene on the morning news. Just something to consider. At the moment I feel a bit ‘removed’ from the scene.

A Fresh Take – My final issue is really one of ‘where are we headed?’ with this novel. At the moment I don’t see anything except a pandemic related, possibly dystopian scenario but, given a potentially crowded ‘pandemic YA novel’ market I do think you need to have something really fresh/different or at least the foreshadowing of something different right from the start. I fear that an editor who picked this first page up would simply assume it was going to be the ‘same-old-same-old’…so I would recommend giving them something fresh that really intrigues them.

TKZers – looking forward to getting your feedback on some of the issues I’ve raised as well as any other comments you have from our brave submitter! It’s hard writing an authentic YA voice, but I think that is certainly one of the strongest elements with this first page.