@jamesscottbell

There’s been a lot of blogosphere chatter about writing success being like a lottery. Something about that metaphor has always bothered me. For in a true lottery you can’t really affect your odds (except by buying more tickets, of course). But is that true for writers?

I don’t think it is. Just putting more books out there (“buying more tickets”) won’t help your chances if the books don’t generate reader interest and loyalty. Productivity and prolificacy are certainly virtues, but to them must be added value.

Hugh Howey had some interesting thoughts recently on timing and luck. Citing Malcolm Gladwell’s book Outliers, Howey highlighted a fascinating factoid:

A list of the 75 wealthiest people in history, which goes all the way back to Cleopatra, shows that 20% were Americans born within 9 years of each other. Between 1831 to 1840, a group that includes Rockefeller, Carnegie, Armour, J.P. Morgan, George Pullman, Marshall Field, and Jay Gould were born. They all became fabulously wealthy in the United States in the 1860s and 1870s, just as the railroad and Wall Street and other industries were exploding.

From this Howey explains how he benefitted greatly from being in the right place at the right time, Kindle-wise. He had started writing in earnest in 2009, just as the neo-self-publishing movement was taking off. He did some things right, like early adoption of KDP Select and serialization. Look at him now.

But there is one thing he says I disagree with: “I know I’m not that good.”

Wrong. He is good. Very good. Woolwould not be what it is without the quality. Which Howey has worked hard to achieve.

Reminds me of the old adage, “Luck is where hard work meets opportunity.” I believe that wholeheartedly.

I went to school with a kid named Robin Yount. He was a natural athlete and an incredible Little League baseball player. In fact, my greatest athletic moment was the day Robin Yount intentionally walked me. Because Yount is now a member of Baseball’s Hall of Fame.

But it wasn’t just his natural giftedness that made him what he was. He happened to have an older brother named Larry, who made it to the big show as a pitcher. I remember riding my bike down to the Little League field one day and seeing Larry pitching ball after ball to his little brother. Robin Yount was lucky in the body and brother he was given. But he still had to work hard. Because he did,he was ready when, at age 18, he got the call from the Milwaukee Brewers.

Hard work meeting opportunity.

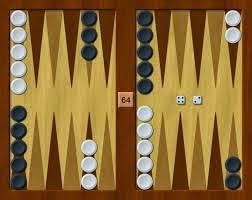

So I wouldn’t call the publishing biz a lottery system. What metaphor would I use? It hit me the other day: writing success is more like my favorite game, backgammon.

Backgammon, which has been around for 5,000 years, is brilliantly conceived. Dice are involved, so there’s always an

element of chance. Someone who is way behind still might win if the dice give him a roll he needs at a crucial moment.

On the other hand, someone who knows how to think strategically, can calculate odds, and takes risks at the right time, will win more often than the average player who depends mostly on the rolling bones.

Early on I studied the game by reading books. I memorized the best opening moves for each roll. I learned how to think about what’s called the “back game,” what the best “points” are to cover, and when it might pay off to leave a “blot.”

And I played a lot of games with friends and, later, on a computer. I discovered a couple of killer, though risky, opening moves. I use them because they can pay off big time, though when they don’t I find myself behind. But I’m willing to take these early chances because they are not foolhardy and I’m confident enough in my skills that I can still come back.

This, it seems to me, is more analogous to the writing life than a lottery. Yes, there is chance involved. I sold my first novel because I happened to be at a convention with an author I had met on the plane. This new acquaintance showed me around the floor, introduced me to people. One of them was a publisher he knew. That publisher just happened to be starting a new publishing house and was looking for material. I pitched him my book and he bought it a few weeks later.

Chance.

But I was also ready for that moment. I had been studying the craft diligently for several years and was committed to a weekly quota of words. I’d written several screenplays and at least one messy novel before completing the project I had with me at the convention.

Work.

Thus, as in backgammon, the greater your skill, the better your chances. The harder you work, the more skill you acquire. Sure, there are different talent levels, and that’s not something we have any control over.

But biology is not destiny, as they say. Unrewarded genius is almost a cliché. Someone with less talent who works hard often outperforms the gifted.

Now, that doesn’t mean you’ll always win big in any one game. If the dice are not your friends, things might not turn out as planned. That book you thought was a sure winner might sink. Or even stink.

But that doesn’t mean you have to stop playing.

Don’t ever worry about the dice. You cannot control them, not even if you shake them hard and shout, “Baby needs a new pair of shoes!” The vagaries of the book market are out of your hands. You can, however, control your work ethic and awareness of opportunity.

Writing success is therefore not a lottery. It’s a game.

Play intelligently, play a lot and try to have some fun, too.

So what about you? Do you believe in pure luck? Or do you believe there is something you can do to goose it?