Category Archives: self-publishing

The State of Self-Publishing at This Moment in Time

Fiction: Plot & Structure was published by Writer’s Digest Books. I wanted it to be practical and immediately useful, the kind of book I was looking for when I was learning how to write. It was my desire to deliver writers from what I call “The Big Lie,” that good fiction writing technique cannot be learned. Bosh. Piffle. Hooey.

NOTE: I’m in travel mode today. Mix it up in the comments and I’ll get to them when I can. Talk about where you are in your publishing journey. What does the landscape look like to you?

Write What You Love

– Huey Lewis and the News

you’re burning to tell. Do that first, and the money will follow. How much, no one can say. But joy tips the balance in your favor. For example, in addition to my novels and novellas, I’m writing short stories about a boxer in 1950s Los Angeles. I make some scratch every month on these. But more than that, I love writing them. It’s a different voice and genre than I normally write in, which has the added benefit of keeping my writing chops sharp.

The Best Way to Market Your Books

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

book. Joanna already runs one of the most helpful websites for indie writers, The Creative Penn. Go there and hang around awhile. You’ll find material aplenty, including a podcast with a certain author of note (at least, of note to himself).

icy cold will make us grit our teeth to even manage one run. But we keep going back because we love it.”

Two More Ways for Writers to Milk the Cash Cow

readers on the discussion board as much as possible,” Reece says.

The End of Discoverability and the Rise of Merit

Key Book Production Costs for Self-Published Authors

After James Scott Bell’s excellent post “We Are All Long Tail Marketers Now”, several side discussions took place in the comments regarding my self-published novel – BLOOD SCORE now available through the Amazon Kindle Select Program (my first time using this program). I’ll have the book discounted until August 1. (I love how the TKZ community gets involved with each post. Thank you.) Questions came up about my editing and production experiences with this novel since it is outside my traditionally published works.

As I mentioned in my comments on Jim’s post, the business end has always been a drain for me. Self-pubbing involves more than promo. It’s production of the actual book and the promo is ongoing (as it is for me with traditional publishers too), but with indie I’m in control of my production schedule, retail pricing and subrights decisions, and can capitalize on promo ops when I want to. Being a hybrid author, straddling traditional and indie publishing, gives me more options and many “irons in the fire.” I have many more points mentioned in another post I did on the subject. On my group YA blog ADR3NALIN3, I did a post on the “Ten Reasons Why I Am Self-Publishing.”

I wanted to dip my toe into the waters of indie with a non-fiction book as well as a short story anthology so I would know what was involved in production and to build up my contacts for service providers. My upcoming full-length novel project will be more about learning promotion. I’ve got loads of personal bookmarks for service providers, but the marketing side of the business needed work on my part. I’ve created a Self-Pub Resource tab on my YA blog-Fringe Dweller. I hope to update it as I go along. For now it encompasses review sites for digital books. That resource tab will be a work in progress as I go.

Basically, here are the indie production costs as I see them:

1.) Edits: $500-$1800+ – This is a tough one to estimate, but important. I’ve seen this cost higher, depending on if you need a book doctor or not. It depends on how much work needs to be done and who you use as editor. A good editor is worth their weight in sales, so shop wisely. Beta readers will only get you so far. Having said that, I’ve had some good and terrible copy editors on my traditionally published books. Being traditionally pubbed does NOT guarantee you will get a good one. At least with indie books, you can make the decision on who to use on current and future projects.

For this project I used authors/editors Alicia Dean and Kathy Wheeler. They helped with formatting and editing and made that effort painless and fun.

2.) Cover $150-400 – This range depends if you are doing a version for print or just digital. The print design costs more because it involves the design of a spine and back cover. You can do a cheaper cover by merely paying for one digital image from iStock or some other provider and add font and do it yourself graphically (not recommended), but a cover needs to look good on a thumbnail and a bad design can kill sales. On BLOOD SCORE, I used Croco Designs and love Frauke Spanuth, the designer. I’ve used her for blog header designs and bookmarks and now covers. She’s a German designer who works for publishers too. Her costs are reasonable on all fronts and she’s easy to work with and fast, but there are many cover designers out there now. Look through portfolios to find one you like.

3.) Formatting $100-150 – You can do this yourself, but I’ve never tried it. There are software programs, but haven’t tried that either

4.) Promotion $50-Whatever – This is totally up to you. There are many free sites that promo ebooks now (that are focused on ereaders), but there are also bundlers who will charge you $50 or so to post promo to 45 sites, etc. I’m hoping to try this with BLOOD SCORE.

5.) ISBN #s – this is an investment for future books. I bought 10 numbers, which keeps the cost down. I think the individual book price is higher to retain your own ISBN#, or you can use the one that Amazon or others assign you for free, but I prefer to have control of my own ISBNs. So this ISBN cost can cost you nothing, unless you decide you want control like I did. So spread $250 across ten books if you retain your own ISBNs.

So all in, you might pay $800 – $2400 (excluding ISBN costs), but you can manage your price to earn 35% – 70% royalty with a better monthly cash flow where you can control the price and promo ops. Using a price of $0.99 you’d earn 35%, but $2.99 or better and your royalty would be 70%. For a novel length book, I might discount it to $.99 for a certain period on release, but then move it up to $4.99. Hard to say what breakeven would be without real sales figures behind it, but you can play with the math.

$4.99 at 70% royalty, you’d have to sell 229 – 687 books to clear the cost range I mentioned. Mind you, this does NOT take into account any promo ad costs and assumes only one price at the higher royalty rate. If you were to move that price point to $2.99 at 70% royalty, your sales would have to be 382 – 1148 to breakeven.

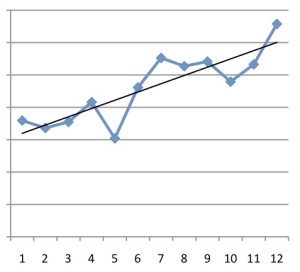

A writer friend of mine shot me some real numbers. (I’m also on an indie writers loop where I hear lots of good info.) It takes having a number of good books to build up your “virtual shelf” of offerings and build your readership. Again, I repeat. Good books. But my crime fiction author acquaintance is seeing $7,000 – $10,000 per month for 8 novels or so, and this will grow as new material gets added. This author crafts a solid book and writes full time.

For me, I like having traditional contracts to fill, but I want the more immediate cash flow too, rather than waiting for royalty statements every 9 months (by the time they reach you). (Antiquated accounting methods and reporting systems for traditional publishers, in a digital age when sales are more immediate through Amazon and other online retailers, are more things that I hope will change.)

The last thing I’d like to talk about is the value of “a la carte” subrights (ie foreign rights, audio, print vs digital). In many deals, these rights are lumped in and assumed to be part of the deal, but should this continue as advances drop? Or if advances drop, shouldn’t the royalty percentage increase to offset the lower upfront money? Subrights have value to the indie author. (Here’s a LINK to a post I did on self-publishing in audio, for example.) If an author gets an offer, but the advance is marginal or too low to tie up copyrights for years (something I am presently experiencing on my back list), do you have options?

You can certainly turn the deal down. That’s one option. I did this with BLOOD SCORE when I got an offer to buy it from a big house. After my experiences, the offer wasn’t good enough to deal with the aftermath of a rights tie up into infinity.

Even if an advance is $10,000-15,000/book, that might not be enough if the terms of the contract are onerous over the long haul. Successful thriller Barry Eisler turned down a deal from a traditional house for $500,000+. That boggled my brain, but no one knows the terms of that deal that made Barry change his mind. He’s a real marketing guru and has a solid readership. Deals are subjective.

These days this is a personal decision each author has to make, but if publishers would negotiate on terms, a marginal advance deal might work if the number of years for digital rights can be limited before they would automatically revert back to the author (ie 2-3 yrs only) or if UK rights were granted but digital rights in the US are retained. Some successful indie authors have retained digital rights, but sold print rights (ie John Locke to Simon and Schuster). With “out of the box” thinking and a little negotiating, some of these marginal deals can be done if the parties agree on specific terms, but I’m not sure traditional houses are open to such change yet.

Food for thought and discussion at TKZ:

1.) If an advance is too low to tie up copy rights, what terms do you think can be negotiated to make the deal happen? Do you think the publishing industry is changing in this regard?

2.) If you’re an aspiring author, would you sign a contract at ANY advance to be published, or do certain contractual terms matter to you?

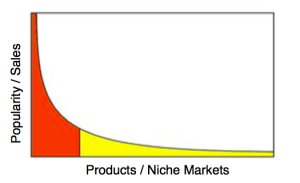

We Are All Long Tail Marketers Now

by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

You don’t need co-op or front of brick-and-mortar store placement.

You don’t need blurbs from star authors.

If you are a traditionally published author, you need to at least set up a footprint in self-publishing. Talk to your agent and editor about this. Think in terms of non-competitive and complementary short-form work. That is platform building of the best kind.

[I’m teaching all day today, but I’d love to hear your comments. Have at it!]

Getting pecked to death:Are critique groups worth it?

I recently joined a critique group. Those who know me might think that’s weird. I’ve been published professionally for more than 20 years. I’ve done my share of teaching and should know how to do this by now. And I have a built-in critique group with my co-author sister Kelly.

So why do I need the tsouris?

Three reasons really. First, just because you’ve written some books doesn’t mean it gets any easier. Second, I now have a second home in the suburbs of the ebook Wild West and you need all the neighbors you can find out here among the wolves and cacti. And third…I’m lonely.

We’ll get back to that last one in a second.

But let’s ask the main question here: Are critique groups worth it? Worth it in time, energy and the bruising your ego will surely take? Should you expose your hatching to the cruel world to be pecked at before it’s barely had the chance to sprout feathers let alone wings? (Whew, labored metaphor alert there).

I used to think critique groups were a waste of time. Maybe that’s because early in my writing life I got involved in one that was really bad. We met at a local bar once a month. (first mistake: combining wine and whine). The members weren’t very good at articulating what was wrong (or even right) in stories and a one guy was really defensive about being rejected by the “Manhattan cabal.” That’s what he actually called New York publishers. I left the group after two sessions, figuring it was cheaper to get depressed at home with a bottle of pinot.

But I think writers are better these days at taking constructive criticism. Maybe it’s because the new world of self-publishing has stripped us of the delusions we might have about how easy it is to write (and sell) a book. Maybe it’s because in these days of change and turmoil, good editors (even those in the Manhattan cabal) are worth their weight in gold. Whatever the forces at work, I think we’re seeing a shift among writers, a new willingness to get help and get better.

So I’ve come to believe that a critique group can be one of the best tools a developing writer can use. Even experienced writers can benefit from them. But there’s a bunch of caveats that go with this. And I’ll get to those in a second too.

First, let me tell you about my little group. There’s four of us and I was the last to join about two months ago after one of the group, Christine Kling, literally sailed off into the sunset. (She’s an avid sailor and decided to pull up anchor and cruise the Caribbean, though she’s back now). That left Sharon Potts, Neil Plakcy, Chris Jackson…and me, the new cucumber.

We meet every two weeks at a Starbucks but in the week prior we send each other our 10 pages. We each then read and “red pencil” our comments on the pages. We use Word’s TRACK CHANGES function. It’s an editing program that lets you insert comments on a document. Track Changes is a little hinky to learn at first but it’s a cool tool. And most editors in publishing are now using it for their author revisions and expect you to know it as well.

Why just 10 pages at a time? Well, too much makes you skim over surfaces. You can really focus down on a book’s problems if you take it in small bites.

What things? We try not to nitpick and line-edit. That’s for second and third drafts and hopefully copy editors. What we try to help each other with is the Big Picture. Where the plot is going into the ditch, where the character development is lacking, and what — and this is important — to the cold eye seems confusing. But we try to stay flexible. We made an exception to our 10-page rule last week for one of our members. She is struggling with a very complex thriller. Her plot had become a hyrdra-beast and she wanted help simplifiying it. So she gave us a concept and we went from there.

At Starbucks, we pick one author to critique and we take turns going over our Track Change comments (we bring printed-out copies to give to each writer). We also encourage the other critiquers to jump into the conversation if they want to add something to the point at hand. These sessions run about four hours, three lattes and at least one pee break.

Have they helped me? Immensely. I am working on a new Louis Kincaid series book and after I offered up my opening chapter, I was told the tone was completely at odds with where I had left my hero in the previous book. That was a major revelation that has made me rethink my first six chapters. I also came to realize I’ve lapsed into a lazy habit of underwriting. My critique mates want a little more description and detail from me. (Ironically, my sister tells me the same thing). I also learned my treatment of my series backstory (always a tricky thing) was deficient. I was mentioning characters and situations from previous books that weren’t explained enough in the present one to stave off confusion.

What’s really good about getting this kind of feedback is not that they are trying to tell me how to write my book. It’s that this will save me valuable time. In rewrites, of course, but also later when I am deeper into the plot. It’s like hiking through a forest. Alone, I might have gotten far into those dark woods, realized I had lost my way back on that first turn, and now I have to backtrack to find my way out. Without falling off the ridge.

My hiking mates aren’t telling me where to go. They’re just keeping me on the path I have already chosen.

So, is a critique group for you? I can’t answer that, of course. But I can pose some questions for you:

1. What kind of group do you need? Ideally, face-to-face. If you can stay within your genre, also good but not essential. Good writing is the same whatever the genre. But I’d stay with fiction. Non-fiction folks have their own unique needs.

2. Where are you in your skill level? You need to find like-minded writers but it’s always better if you can link up with some folks who’ve been published. As the saying goes, you want to play tennis with someone better than you or you never improve your game. But be willing to take the heat. If the group seems like a mere pity-party — ie, everyone bitching about their lack of success — get out as soon as you can. It’s cathartic to exchange tales of woe but it should be limited to small-talk after the hard work is done.

3. Where can you find a critique group? If you’re isolated geographically, there are online groups but it’s pretty gnarly out there, almost like cyber-dating. (There’s one group, Ladies Who Critique, that’s females-only). Start here for a list. The best way, I think, is through writers organizations. I found my group via contacts I made through my Mystery Writers of America Florida chapter. If the organization doesn’t offer critiques, network and start one yourself. All you need is two or three other committed people. Here’s some good advice on starting your own.

I can also give you some advice on how to handle yourself if you do decide to join a group:

1. Make a commitment. You’ll get only as good as you give. If you join up, be willing to spend whatever time it takes helping the others with their WIPs. Nobody likes the guy who shows up at the party empty-handed, drinks all the good booze and sits in the corner with nothing to say.

2. Be tough but kind. The best editors I’ve had always know how to make revision letters sound like they are really praise letters. They always tell you what you did brilliantly before they smack you upside the head and tell you where you royally screwed up.

3. Don’t get defensive. We are all soft-shelled about our writing but if you can’t take constructive criticism, don’t join a group. Hell, don’t even try to be a real writer for that matter. At our last session, I got defensive about fried pickles. My hero Louis orders a basket of fried pickles. It was one throwaway line but one of my critique buddies wanted more about the pickles. (It’s hard to explain but she was right.) I spent five minutes trying to justify why I didn’t want to write more about those friggin pickles. Later, I realized it had nothing to do with pickles and everything do to with me being prickly.

4. Don’t ever say “Yeah, but…” This is a variation on No. 3. One of your critique mates says, “I can’t figure out what is going on in this scene where the guy is stealing the fried pickles.” And you say, “Yeah but if you just wait until chapter 26, it will all be explained.” If someone is confused by what you’ve written you should listen to them. Misdirection is a great writer’s tool. But it is not the same as confusion.

5. Don’t get depressed. Having folks tell you what is wrong with your story is not easy to hear. But a good critique group can be really inspiring. It can teach you that all writers struggle, that first drafts are never meant to be perfect, and that you can, despite what all the demons in your head are whispering, fix it. Yeah, you might feel like that guy in the picture at the beginning of this blog — that’s Prometheus, who Zeus tied to a rock and sent down an eagle to peck the guy’s liver to shreds. But you can also get a big dose of camaraderie through a good critique group.

And that brings me back to my last point — the thing I said about feeling lonely.

We all do, right? We sit here in our old yoga pants and Bob Seger t-shirts, poking away at our keyboards, hoping this STUFF we are storing away each day might actually coalese into a book and be read someday. We surf the internet, read articles about how to improve our craft and blogs about how to market them. But sometimes, as that great western philosopher Bruce Springsteen says, all we really need is some human touch.

We need to know we’re not alone. We need to hear other footsteps behind us on the path.