by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

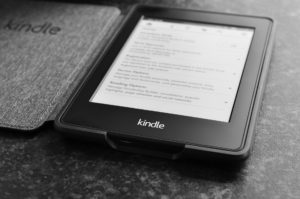

The Kindle turns ten next month. My, how that little baby has grown!

The Kindle turns ten next month. My, how that little baby has grown!

When Amazon’s ereader first came out (November 19, 2007 to be exact), I sensed most people were skeptical about the future of digital reading. The Sony Reader had been around for years but failed to take hold. “Electronic books” were thought to be the coming thing around Y2K. Publishers Weekly even started a section to cover the subject, but later dropped it due to failure to launch.

Clearly, serious readers preferred paper. So the Kindle would probably sell to some early adopters, but likely would not revolutionize anything.

**clears throat**

In 2008, Oprah Winfrey gave the Kindle her endorsement. Talk about a boost! Then people began to realize they could have all the works of Dickens and Dostoevsky on a single device which they could take on a plane or a train or (in L.A. commuter traffic) an automobile. Pretty doggone cool!

And the biz mavens realized that Amazon was (as always, it seems) making a powerful and forward-thinking business move—selling the Kindle as a gateway to their massive bookstore.

Here at TKZ, we were analyzing all this from the start. On Kindle’s one-year anniversary our own Kathryn Lilley wrote:

I think it’s time for all of us to stop mourning the nongrowth of paper book sales, and celebrate the new digital age. It’s the future. Let’s embrace it. For example, last week when I posted, I was freaking out about the changes in the industry. This week, I have decided to reframe my thoughts about the book publishing crisis, and seek out the hidden opportunities in those changes.

Because ready or not, the digital era is here. Kindle products like the Oasis are still going strong. In fact, this review of Oasis is spot on.

And what did all this mean for authors? Well, beginning in 2009 or so, it became apparent that Amazon was presenting a viable new way for writers to get published—by their own selves!

And get this: by offering authors an unheard of 70% royalty split!

The lit hit the fan.

A complete unknown named Amanda Hocking made a cool couple of million dollars publishing directly on Amazon!

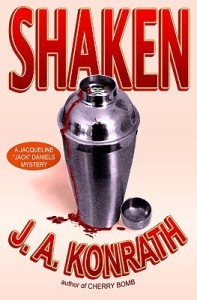

This got the attention of many, including TKZ emeritus Boyd Morrison, and a mainstream mystery author by the name of Joe Konrath who, via his blog, began to champion the new digital possibilities.

When I went to Bouchercon in San Francisco in October of 2010, everybody was wondering how to get in on the ebook thing without ticking off their agent or publisher. Agents (and I heard several) were warning writers not to “go there” for fear it would jeopardize their careers. Publishers were not at all sanguine about their authors moonlighting with a company they saw as their biggest threat. Some writers even got sued or terminated over this.

But the money was dropping off Kindle trees! That could not be ignored.

A funny thing happened at that Bouchercon. I was sitting with a couple of writer friends in the lobby of the SF Hyatt Regency, talking about all this, when Joe Konrath arrived and made his way to the bar area. He was flocked by fellow authors peppering him with questions.

The next day, at lunchtime, I was outside the Hyatt and spotted Mr. Konrath and one Barry Eisler walking and talking excitedly along the sidewalk. I thought, “What is that all about?”

A few months later I found out. Mr. Eisler, a New York Times bestselling thriller author, turned down half a million bucks from his publisher in order to publish with Amazon!

It was the talk of the industry. I saw it as a real tipping point. In fact, I gave it a name: “The Eisler Sanction.”

Self-publishing was getting serious.

I put my own toe in the E waters in February of 2011. Now I’m all wet.

So ten years after the birth of the Kindle, what have we seen?

1. Kindle devices and apps are awesome. I’m currently reading the two-volume memoir of Ulysses S. Grant, easily highlighting passages I want to review later. The General is bivouacked on my phone. Cost me 99¢.

2. While other ereaders have appeared—notably Nook and Kobo—the Kindle is dominant and unlikely to lose market share. The poor Nook, which is also a cool device, is hanging by a thread.

3. Kindle Direct Publishing has saved the careers of thousands of midlist writers, and created the careers of thousands more who are making good-to-massive lettuce every month. Those who are doing well have mastered some basic practices but also concentrate on the most important thing: quality and production.

4. The traditional publishing industry was hit hard by the digital disruption. There have been mergers, layoffs, shrinking profits and even a DOJ smackdown.

5. But the Forbidden City is still open for business. And while large-advance deals for debut authors are becoming as rare as the blue-footed booby, they still happen.

6. There has been chatter about the “comeback” of print books, but it appears that most of any increase in print sales can be traced to … Amazon. (And here’s a counterintuitive development: Millennials may actually prefer print books!)

7. Big bookstores took a huge hit due to e-commerce. The massive Borders chain of stores went down, followed by Family Christian. Barnes & Noble stores have been closing steadily for the last eight years, a trend that will likely continue.

8. However, local independent bookstores may be emerging through the cracks. Oh, and guess who else is opening up physical stores? Amazon.

9. On the other hand, many niche bookstores are closing. The latest is Seattle’s Mystery Bookshop.

10. We’ve reached a period of relative stasis in the “self v. trad wars.” From 2010 to 2014 or so, it seemed like we’d get blogosphere firestorms every week cheering for, or predicting the demise of, Big Pub. There was also a lot of “gold rush” talk on the indie side. Reality, as it is wont to do, has settled things down. There’s a lot of information out there now (e.g., Author Earnings reports) and the savvy players have a better handle on where they stand.

In an episode of Downton Abbey, when it became clear that the old ways of life were on the way out, never to return, Carson the butler mused, “The nature of life is not permanence, but flux.”

Kindle brought the flux. And a decade later, we’re living it.

What do you say, TKZers? What are your reflections on the 10th birthday of the Kindle?