by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

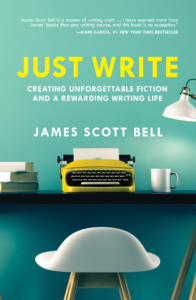

Something new from Writer’s Digest Books.

I got together with the great team at WD and collected some of my previous articles and posts on writing, added new material and organized everything under two parts. The first part is about kicking up your fiction writing not just one notch, but several; the second is about enjoying your writing life, making it all it can be. The book is available at your local bookstore and online:

AMAZON I BARNES & NOBLE I KOBO I iBOOKS I GOOGLE BOOKS

Sometimes I’m asked why I teach writing. Here’s my answer.

I teach because I know what it feels like to be an unpublished writer wondering if he has the stuff. For about ten years after college I was of the belief that writing fiction could not be taught. I’d been told that writers are born, not made. I was warned not to waste money on craft books.

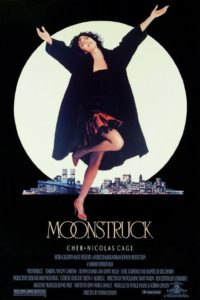

But when I went to see Moonstruck one afternoon with my wife, the urge to  write hit me again with full force. That film bowled me over with its originality, characters, dialogue, and heart. I wanted so much to be able to write something that would make people feel the way I was feeling. I was a practicing lawyer then, so mostly I was making people feel irritated. But I said to myself, “Self, you learned the law by studying. Let’s just see if you can learn to write the same way, despite what those naysayers told you. At least give it a shot!”

write hit me again with full force. That film bowled me over with its originality, characters, dialogue, and heart. I wanted so much to be able to write something that would make people feel the way I was feeling. I was a practicing lawyer then, so mostly I was making people feel irritated. But I said to myself, “Self, you learned the law by studying. Let’s just see if you can learn to write the same way, despite what those naysayers told you. At least give it a shot!”

I began with screenwriting. The seminal book was Syd Field’s Screenplay. He broke down the three-act structure, and I spent a year watching movies, timing them, figuring out what happens at various points, and why. Field, however, had a notion about the first “plot point” that was not entirely clear to me. He said it “spins the action” into a different direction. I felt there had to be something more to it than that.

So I intensified my study on that structural point. And one day it hit me. What has to happen here is some event that forces the Lead into the confrontation of Act II, and is vitally connected to the main conflict of the story. It is also a place from which the Lead cannot retreat. It was like going through a doorway of no return. I tested this against classic movies, and lo and behold, there it was.

I got so excited about this I began to share the Doorway of No Return theory with other writers. They’d stroke their chins and think about it and then say, “Yeah. I see that.” And when they saw, it made me all the more jazzed.

So I kept studying, trying things, creating techniques for myself. When something worked, I journaled about it. I was like Dr. Jekyll keeping track of all the experiments on himself. Only instead of turning into Mr. Hyde I was becoming a writer of saleable prose.

After landing a five-book contract I began to teach at conferences, and started writing articles for Writer’s Digest. Later, I was the WD fiction columnist. And all the time I had this in mind: I wanted people to know it CAN be done. You CAN learn the craft. You CAN get better. The naysayers are touting a Big Lie! Don’t believe it!

And I’d hear from folks that they were learning and growing and getting agents and contracts and hitting bestseller lists. The Big Lie was dead!

In fact, the day I wrote the above paragraph (Friday), I got this tweet:

Time to dismantle the Big Lie! Thanks for the inspiration and help @jamesscottbell

I’m doing this! #writer pic.twitter.com/6zpo3R50Uy

— Inkwell Musings (@inkwellmusings) April 29, 2016

So keep writing, friends. Keep learning. Those are parallel tracks. I keep on both of them myself and have ever since that day I walked into the sunlight after seeing Moonstruck. I still get pumped about trying things and figuring out what works, what makes my own fiction better. And I still love to share what I learn with fellow writers, as do all my blogmates here at TKZ.

That’s why I teach writing.