James Scott Bell

I was in New York last month for the annual Writer’s Digest conference. Mrs. B and I got there a couple of days early to do some New Yorky things—like going to see Alan Rickman in a new Broadway play about writers, strolling through a snowy Central Park, sampling the hot pastrami at Katz’s Deli.

But the highlight by far was getting to sit down for an hour with America’s greatest living writer.

That designation, of course, is highly subjective. I would think that it would have to be someone who’s been at it a long time. Half a century at least. And someone who has put out a prodigious amount of work that is of the highest quality.

In fiction, Ray Bradbury snaps immediately to mind. Living in So Cal, I’ve had the chance to meet and chat with Mr. Bradbury on a few occasions. He is one of my writing heroes and would get a lot of “greatest living writer” votes.

But if we also include non-fiction writing in there (and why shouldn’t we?) the man we met with definitely deserves a place at the table.

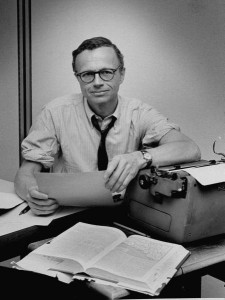

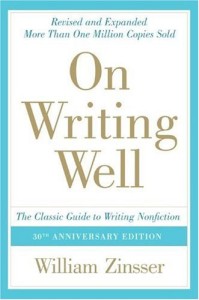

William Zinsser is, of course, the author of the classic On Writing Well. I picked up a first edition in hardcover when it came out, and it’s been something of a “bible” for me ever since. Whenever I write my non-fiction books, an article (or blog post!) I am always thinking Zinsser—cut the clutter! Believe in your own identity! Care about the words, because they’re the only tools you’ve got!

Zinsser the writer is a master of the personal essay. He’s like Mark Twain without the overt jokiness. His humor pads up softly and tickles you, emerging naturally out of the subject. That’s how Zinsser was trained, starting with his time at the New York Herald-Tribune. The story was the star, not the ego of the reporter. Getting the facts right was job number one. Mendacious embellishment was the gravest of sins.

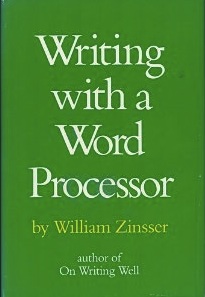

Mr. Zinsser has written eighteen books on a variety of subjects. My absolute favorite is a little gem of cultural history, Writing With a Word Processor.

Published in 1983, it is the account of his transition from typewriter to computer. It still makes me laugh. Even though the technology aspect is dated, the writing remains fresh, clear and hilarious. I’ll sometimes take it off the shelf and read a random chapter to my wife, and we’ll laugh again at how he captured that historical and hysterical slice of life.

So when Mr. Zinsser consented to have Cindy and me up to his apartment on our recent trip, I was ecstatic. It was also an honor, for he told us that we were the first “guinea pigs” in this latest phase of his life.

You see, glaucoma has forced William Zinsser, at age 89, to finally cease his prodigious output of the written word. He has decided now to concentrate on his role as a mentor and encourager of writers, to help them in any way he can. “I’m still working out how that will look,” he said.

So we sat and talked. About writing and his career. He is a fourth generation New Yorker. He’s always lived in the city, not counting a stint in North Africa and Italy during WWII, and in New Haven when he taught at Yale.

After the war, he “cadged” a job at the newspaper he grew up with, the Herald-Tribune.It was here he learned the lessons on writing he would live by and pass on. As to the facts: Get it right. As to style: Second best is no good.

He did his work on a classic Underwood typewriter. “I’m a child of paper,” he told us. “And that Underwood is still in my closet.”

Zinsser loved working on the newspaper, but saw it sadly decline in the late fifties due to mismanagement. When he couldn’t take it anymore he quit and became a freelance writer. This was quite a switch, from regular paycheck to the uncertainty and fickleness of the freelance life.

It didn’t phase him. “You have to make your own luck,” he said. “No one’s going to do it for you.”

So he wrote for the top magazines––Life, Look, The Saturday Evening Post––until they died. He made more of his own luck by turning to teaching––at Yale and later at the Columbia School of Journalism and the New School.

He finally put his words of writing wisdom into On Writing Well, which doesn’t sound like the title of a blockbuster. But, 1.5 million copies later, it certainly qualifies.

I don’t care if you write fiction or non-fiction, books or blogs. If you write anything that has to connect with a wide readership, and you don’t own a copy of On Writing Well, order it now. It needs to be in every writer’s library.

I would also highly recommend Mr. Zinsser’s book about his own writing journey, Writing Places. It is one of the most enjoyable memoirs I’ve ever read.

You can also read his most recent essays online. For two years, until his retirement, he wrote a weekly essay for The American Scholar. Check them out. It’s a master class in writing.

When our chat was over and we were about to leave, Mr. Zinsser reflected on the new technologies available for the writer these days. They are about convenience, but not essence. They don’t fundamentally change what writing has always been about.

“We are all in the storytelling business,” he said, “whatever the technology you’re set up with. Most of what I’ve done, frankly, is tell a story.”