For those of you who came here today to learn a little more about blowing stuff up–which I promised to discuss–you’re likely to be a little disappointed. Fact is, there’s breaking news that takes precedence. On December 19, at 3:00 pm (and probably again, later) getTV will rebroadcast Perry Como’s Early American Christmas, which first aired on December 12, 1978. It features the College of William and Mary Choir, of which I was a part. Here’s a screen shot of my 21-year-old self in the company of my dear friend, Jim Shaffran (who is now part of the permanent company of the Washington National Opera).

That was taken while shooting a tavern scene, the entirety of which can be seen here. It’s worth noting that shooting started somewhere around 5:00 a.m., encompassed many takes, and that the tankards all contained real beer. More on that later.

We had known from the beginning of the school year that the Perry Como Christmas Special would be shot in Williamsburg, and that the choir would be involved. We also knew that the Men of the Choir (as we called ourselves) would have a featured part, but as I recall, we didn’t know until very late in the game that it would be a costumed performance. That meant visits to the Colonial Williamsburg costume shop, fittings, and, well, responsibility. By the time I was a senior, I had designed my entire existence around as little responsibility as possible. But I stepped up and, I have to say, rocked the outfit.

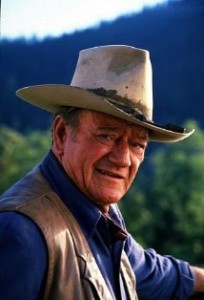

Was I concerned that the shooting schedule fell squarely in the middle of midterm exams? Well, maybe. But I was going to get to meet John Wayne. No, really. John Friggin Wayne. I could repeat my senior year if I had to, but, come on . . . John Wayne!

First a little bit about Mr. Wayne. For me, being a male of a certain age, the Duke exhibited pretty much everything that defined being a man’s man. In person, he was huge. When he shook my hand, he engulfed pretty much the whole thing, up to the wrist. He spoke in real life in that same halting syntax that you hear in the movies. And he was cranky. (We didn’t know it at the time, but this Christmas special would be one of his last performances before passing away.)

If you’ve ever done any kind of video, you know how long and boring the setup for any shot can be. While the crews did their thing, Perry worked the crowd. We were at least one–maybe two–flagons of ale into the morning before the director said, “action” for the first time. If you listen carefully to Perry, I think you’ll hear that he was a bit lolly-tongued when it came time for “I Saw Three Ships.” And he kept blowing takes. Full disclosure: As a practical matter, it was impossible for us to blow takes because the singing you hear was all prerecorded. It’s all our voices, but done in a studio. In the video, we’re singing along with the playback.

As the morning–and the takes–ground on, John Wayne’s fuse grew shorter and shorter.

And the flagons flowed. I was pretty much an Olympic class beer drinker when I was 21, and I remember realizing that I was ripshit well before noon. Not shown in the video clip is the climax of the tavern scene where Perry and the Duke toast us with, “Merry Christmas!” and we respond in kind, upending the mugs of beer and their contents. And then a new mug would appear. And of course, the scene had to be shot from every angle.

By the time it ended, the Duke was, well, pissed off. Made things a little awkward on the set, but Perry seemed to be having the time of his life.

I had a blast that day. At the end of the shooting, around 1:30, as I recall, the director said they needed extras for other scenes they’d be shooting that day and night and asked if any of us would like to stick around. What the hell? No one looks at senior year grades anyway. If you watch the entire special and look closely, you’ll see me walking in and around a number of other scenes. You’ll also see a couple of stunning performances by the entire choir.

For as long as I can remember, my mother had a serious crush on Perry Como, the the news of my involvement in the Christmas special was particularly well-received in Springfield, Virginia. To hear her tell the story, the show was really about Perry and me. Moms are like that. In one especially amusing anecdote, I called home to relay the events of the shooting day. While telling the story of the endless flagons of ale and Perry’s progressing inebriation, I mentioned in passing that during one of the breaks, Perry and I chatted while peeing at adjacent urinals. My mother’s question: “Did you peek?” Me: “Mom!”

When the very long day was over, and crews were breaking things down, I found myself face-to-face with John Wayne with no others pulling at his attention. I told him that I was a huge fan of his work, and what an honor it was to have spent the day with him, and if I could please have an autograph. He said, and I quote, “No.” Then he walked away. I figure he wasn’t feeling well.

But I got to meet him. And I shook his hand.

We folks at The Killzone will be taking our Holiday Hiatus before my next posting time comes around, so let me take this opportunity to wish all of you a wonderful time with family and friends, good food and lots of laughter. I’ll see you on the flip, in 2017, and I promise we’ll start by blowing stuff up again.