All our links need to work. Especially buy links. What if the link to your new release prevents your ARC readers from leaving reviews on Amazon? What if the link prevents all your readers from leaving reviews on Amazon, even verified purchase reviews? Or worse, Amazon shuts down your account because you’re violating their rules.

It happens more often than you may think, and many times the violation stems from a dirty link — the link you used in your marketing. That’s how important it is to clean your links. Trad-pub authors, don’t think this subject doesn’t apply to you. It does. In fact, that’s where I learned about dirty links, from my very first publisher.

What is a dirty link?

Your new book baby goes live on Amazon. If you search for the title on Amazon rather than go through your KDP dashboard, you’ll get a link that looks like this: https://www.amazon.com/Tracking-Mayhem-Sue-Coletta/dp/B0C91HLCJ6/ref=sr_1_1?crid=1EHIC52HI29T3&keywords=Tracking+Mayhem&qid=1692542716&s=books&sprefix=tracking+mayhem%2Cstripbooks%2C107&sr=1-1

That is a dirty link. It even looks ugly, right?

I want to draw your attention to this half of the link:

ref=sr_1_1?crid=1EHIC52HI29T3&keywords=Tracking+Mayhem&qid=1692542716&s=books&sprefix=tracking+mayhem%2Cstripbooks%2C107&sr=1-1

Everything after “ref” is filled with information for Amazon, information that can bite you in the butt. This tells Amazon who searched for the book. If the author conducted the search, then everyone who uses that link must be friends or family of said author.

Though you and I know that’s a ridiculous statement, Amazon disagrees.

If you have a connection to a reader, even if it’s on social media, Amazon presumes they’ll rate your book favorably. Doesn’t matter if you have 1M friends or followers. If someone buys your book from that dirty link, you are friends and/or family in Amazon’s eyes. Period. Hence why it’s also never a good idea to link your Goodreads (Amazon owned) to your Facebook.

As you probably know, Amazon doesn’t allow friends and/or family to review your book. If they do, Amazon can delete it from your book’s page. If you continue to violate this rule, Amazon can shut down your account.

So, the first thing you should do is delete everything from “ref” forward, leaving you with this: https://www.amazon.com/Tracking-Mayhem-Sue-Coletta/dp/B0C91HLCJ6/

Looks better, right? That link is now clean, but we can shorten it even more. The title and author are also irrelevant as far as the link is concerned. Let’s delete both. https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0C91HLCJ6/

If you’re working with limited space, you also don’t need “www.” You’ll end up with this: https://amazon.com/dp/B0C91HLCJ6/

Now that’s a spotless link! A far cry from the original, right? And with no added information for Amazon to track.

While we’re on the subject of links…

Most profile sections on social media only allow you to include one link. Wouldn’t it be great if you could house all your books, website, blog, newsletter sign-up, etc. under one link rather than choosing which one to include? You can!

The creative minds behind LinkTree solved the one-link problem.

Did I mention it’s free? When you sign up, they’ll ask you to customize your link with your name. Don’t use your book title or a clever alias. That defeats the purpose. You could use your pen name if that’s the only name you write under. Or create a new link for additional pen names.

Personally, I only want one link, but you do you.

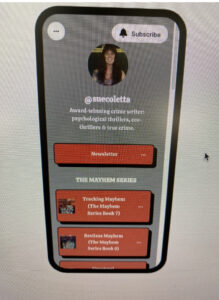

Here’s how mine looks: https://linktr.ee/suecoletta

You can customize the links inside, with headings, color, button style, thumbnail images, etc.

Of course, you can upgrade for statistical data and other bells and whistles, like affiliate marketing. Though the free account does accept affiliate links for books without the upgrade.

Of course, you can upgrade for statistical data and other bells and whistles, like affiliate marketing. Though the free account does accept affiliate links for books without the upgrade.

Are you using affiliate links?

If you’re unfamiliar with affiliate marketing, here’s what Amazon says about its program:

Amazon’s affiliate program, also known as Amazon Associates, is an affiliate marketing program that allows users to monetize their websites, blogs, or social media. Amazon affiliate users simply place links to Amazon products on their site, and when a customer makes a purchase via one of their links, the user receives a commission.

Every time we pay for a promo spot, you can bet the book site is including their affiliate ID in your link. Which is fine. It’s their site.

Quick funny story…

When my debut released, I thought a certain book site was the cat’s meow for sending me a universal book link to use in all future marketing. So nice, right? Yes and no. What I discovered later was they included their affiliate ID in the universal link. So, for well over a year, I gave away commissions that I could’ve earned. Kudos to them. They got me good. Now, the only links I use are the ones I create. If anyone’s gonna earn commissions from my marketing efforts, it’s me.

Do you use affiliate links? Do you clean your links? Have you ever had reviews removed by Amazon? Has a book site ever created a universal link for you? 😉

As writers, it shouldn’t surprise you to learn that even while silent, our bodies speak volumes. Nonverbal cues — body language — are the physical behavior, expressions, and mannerisms that communicate how we really feel.

As writers, it shouldn’t surprise you to learn that even while silent, our bodies speak volumes. Nonverbal cues — body language — are the physical behavior, expressions, and mannerisms that communicate how we really feel.

By Elaine Viets

By Elaine Viets Murder seems to touch us all. When I thought about it, I realized I’d watched a murderer grow up in my city neighborhood. We lived on a shady street with big, old redbrick houses. One house, halfway down the block, was known as “the trouble house.” The police were there two or three times a week. The neighbors often called the cops on the boy, who I’ll call Billy, because that’s not his name. Billy broke windows, supposedly stole things out of yards, and may have tortured a stray cat.

Murder seems to touch us all. When I thought about it, I realized I’d watched a murderer grow up in my city neighborhood. We lived on a shady street with big, old redbrick houses. One house, halfway down the block, was known as “the trouble house.” The police were there two or three times a week. The neighbors often called the cops on the boy, who I’ll call Billy, because that’s not his name. Billy broke windows, supposedly stole things out of yards, and may have tortured a stray cat. In 2020, some 17,754 people were murdered in the USA. More than 40 people are murdered every day in the US. That statistic led to a jury room full of raised hands, and lives filled with sorrow and regret.

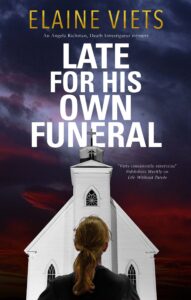

In 2020, some 17,754 people were murdered in the USA. More than 40 people are murdered every day in the US. That statistic led to a jury room full of raised hands, and lives filled with sorrow and regret. Late for His Own Funeral “ is a fascinating exploration of sex workers, high society, and the ways in which they feed off of one another.” — Kings River Life. Buy it here:

Late for His Own Funeral “ is a fascinating exploration of sex workers, high society, and the ways in which they feed off of one another.” — Kings River Life. Buy it here:

But there’s one name that deserves to be mentioned here, for he was a quadruple threat: he could sing, dance, and act equally well in comedy or drama. His star flew across stage, screen, TV, and Vegas.

But there’s one name that deserves to be mentioned here, for he was a quadruple threat: he could sing, dance, and act equally well in comedy or drama. His star flew across stage, screen, TV, and Vegas.