by James Scott Bell

@jamesscottbell

Before there was James Patterson there was Sidney Sheldon.

Before there was James Patterson there was Sidney Sheldon.

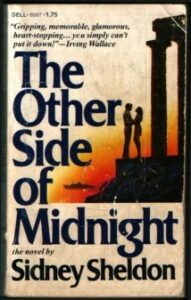

His second novel, The Other Side of Midnight (1973) was a monster bestseller. A string of #1 NYT bestsellers followed. Sheldon sold an estimated 400 million books before he died.

And he didn’t start writing fiction until he was in his early 50s!

Before that Sidney Sheldon led, if you’ll pardon the expression, a storied life.

He was born in Chicago in 1917, to Russian-Jewish parents. He almost committed suicide at age 17 (it wasn’t until decades later that he was diagnosed as bipolar). What pulled him back from the brink was writing. He pursued it with passion, and the results were astounding.

He had two hit shows on Broadway at the age of twenty-seven.

After World War II, he became a studio writer in Hollywood. His screenplay for the Cary Grant comedy The Bachelor and the Bobby-Soxer won the Academy Award for best screenplay of 1947. Sheldon was 30 years old.

Not that all this was a smooth trajectory toward the top. Far from it. Sheldon suffered as many setbacks as he had triumphs. He described the writer’s life (especially in Hollywood) as being on an elevator. Sometimes it’s up. Sometimes it’d down. And if it stays down, you need to get off.

Sheldon continued to ride that elevator in the 1950s. Up and down. He even had a great idea for a Broadway show ripped off from him.

In the early 60s he decided to take a crack at television. He created the hit series The Patty Duke Show, and get this: Sidney Sheldon himself wrote virtually every episode himself. Over 100 in all!

Do you know how absolutely amazing that is? To be that sharp and funny week after week? And all this while suffering from what at the time was called manic-depression.

But even more amazing was the personal strength and courage he and his wife showed through two highly emotional tragedies.

They had a baby girl born with spina bifida and, despite all the best medical care, she died in infancy. After a long period of mourning they decided to adopt a child. An unwed mother whose boyfriend had left her gave the baby up. They brought her home and for six months loved her and bonded with her.

But under California law at that time, the biological mother could change her mind within six months. This mother did, and one day the authorities came and took the Sheldon’s baby daughter away.

Sheldon and his wife turned to religion for solace. Sidney (now being treated with Lithium) continued to work. He started developing a new television show from an idea he’d had for a long time. It was about an astronaut who finds a bottle on the beach and frees a genie. But this genie would not be the big, lumbering, male giant of tradition. Oh no. This one would be a babe. That’s how I Dream of Jeannie was born.

During this time, the 1960s, Sheldon kept noodling on a thriller idea about a psychiatrist who is marked for murder though he has no enemies. He must use his professional skill to figure out who is stalking him. That became Sheldon’s first novel, The Naked Face. It was published in 1970 and won the Edgar Award from the Mystery Writers of America.

Sheldon caught the novel-writing bug, big time. Here he could create whatever world he wanted, without regard to budgets, sets, actors, or restrictions of any kind—especially the story-by-committee nonsense of Hollywood.

He had an unsold screenplay in his drawer and turned it into The Other Side of Midnight. Sheldon was 56 when this novel rocketed him into the literary stratosphere.

His last thriller, Are You Afraid of the Dark, was published in 2004, when Sheldon was 87.

Sidney Sheldon is the only writer ever to have won a Tony, an Oscar, and an Edgar Award. Let’s see if anybody ever does that again!

In The Writer’s Handbook 1989, Sheldon talked about his method. Here’s some of what he said.

The Secret

Sheldon was asked, What are some of the devices you have found most successful in getting your readers to ask breathlessly, “What’s next?”

The secret is simple: Take a group of interesting characters and put them in harrowing situations. I try to end each chapter with a cliffhanger, so that the reader must turn just one more page to find out what happens next. Another thing I do is to cut out everything that is extraneous to the story I am telling.

Simple to understand, yes. To put into practice book after book, well, that’s something else again. But you can learn how to write more interesting characters, how to make a form of death (physical, professional, psychological) hang over every scene (“harrowing situations”), and ways to end a scene or chapter with what I call a “Read On Prompt.” This is all to be filed under Craft Study.

Process

Sheldon was a “discovery writer” or “pantser.” But let’s hear what that actually meant.

When he began a book, all he had in mind was a character. He then dictated to his secretary, developing the character, bringing others in, letting them interact. “I have no idea where the story is going to lead me.”

But that is only for the first draft. Then came the work.

The first rewrite will be very extensive. I will discard a hundred or two hundred pages at a time, tightening the book and clarifying the characters.

A hundred to two hundred pages? Yikes! There’s more: “I usually do up to a dozen rewrites of a manuscript.” Yikes and gulp!

He would spend a year or year-and-a-half rewriting and polishing a book. This paid off, of course. Big time.

He did have a caveat:

I want to emphasize that I do not recommend this way of working for any but the most experienced writers, since writing without an outline can lead to a lot of blind alleys. For a beginning writer, I think an outline is very important…It is a good idea to have a road map to tell you where you are going.

The Leave-Off Trick

Like Hemingway, Sheldon would end his day’s work after beginning a new scene. Sometimes he’d quit mid-sentence. “In the morning, when you are ready to go to work, you have already begun the new scene.”

Also, he would begin his writing sessions by lightly going over the previous day’s work.

The Mid-Plot Blues

Sheldon said he usually wanted to give up in the middle of his novels. I experienced this early in my career and came to call it the 30k Brick Wall. I found that several successful writers reported the same thing.

Why should this be? Maybe because by 30k you’ve got the engine revved up and are now staring at that long middle, wondering if you’ve got the right foundation and enough plot to make it to the end. The writing willies, if you will.

Formerly, my solution was simply to take a day to brood and imagine and jot notes, maybe adding a new character or two. Then, once I started up again, one scene at a time, I would get back into the flow. That works.

Now I find that if I have my signpost scenes in place, especially the mirror moment, I don’t hit the wall anymore.

The Emotion Quotient

You get your readers emotionally involved in your characters by being emotionally involved yourself. Your characters must come alive for you. When you are writing about them, you have to feel all the emotions they are going through—hunger, pain, joy, despair. If you suffer along with them and care what happens to them, so will the reader.

Wise words with which we all should agree.

Minor Characters

I refer to minor characters as “spice.” They are an opportunity to delight readers, so don’t waste them by making them clichés.

Sheldon:

Every character should be as distinctive and colorful as possible. Make that character physically unusual, or give him an exotic background or philosophy. The reader should remember the minor characters as well as the protagonists.

I’ll close by recommending Sheldon’s memoir The Other Side of Me. I love reading bios of authors. This one is entertaining, instructive, and inspirational.

What do you think of Mr. Sheldon’s advice?

Jim,

Fascinating reading about the life of Sidney Sheldon. Thank you for this insightful piece with many lessons for every writer. I’m tracking down a copy of his memoir to learn more.

Terry

author of Book Proposals That $ell, 21 Secrets To Speed Your Success (Revised Edition)

Thanks, Terry. You will enjoy his memoir.

So much of what you talk about in this post I was pondering yesterday while wrestling with a manuscript. Things like how to convey emotion in a way readers feel, and are not told, keeping the tension up, etc.

I have often heard the advice to make each character (even minors) distinctive in some way. This gets even more stressful as a writer if you are developing a series–characters (even minor ones) who will show up again & again. As noted, making them distinctive is a great way to ensure they are memorable & the reader can keep them straight. Bad news–when you’re writing & trying to do that, you wonder if you are writing minor characters distinctively in a good way or in a way that seems hokey–an apparent device. I just have to keep writing and practicing.

And yes, I’m at the midpoint wall. On this project I thinly outlined. I have a general idea of what happened & who did it. This is my first mystery, & I’m wrestling with how to take the investigation through step by step. We have to juggle characters in any genre of book, but I’m finding fascinating the process of juggling those characters for a mystery–it’s a lot different than writing, say, historical fiction. But it’s all part of the learning curve.

As to Sheldon, his name was big during my growing up years. As soon as I saw his name in the post, my thoughts first went to I Dream of Jeannie because I remember him from the TV side of things. I had forgotten he’d done books as well.

Common struggles, BK. I’ve been through them myself.

For minor characters, start with one distinctive tag. For example, I had two minor characters, older women. I gave one of them heavy lipstick, and the other curly hair. My main character thus refers to them as Curls and Red.

Fascinating story about Sidney Sheldon, Jim. I Dream of Jeannie and the Patty Duke Show were TV staples growing up and his paperbacks were always on drugstore spinners. His books were considered too “trashy” for the local library so I didn’t get to read them.

The sample excerpt of his bio is a textbook on how to hook the reader–fascinating characters, both major and minor, who are emotionally engaging, cliff hangers, setbacks and struggles to overcome obstacles, and roller coaster pacing. What a master.

I seem to recall that trashy label as well. All I know is, when I started reading The Other Side of Midnight shortly after it came out, I couldn’t put it down.

He sure put his snobbish critics to shame, didn’t he?

This is fascinating, Jim. I only knew Sidney Sheldon’s name from TV, but I hadn’t read any of his books.

I identify strongly with Sheldon’s process. (I wish I could identify with his success!) It takes me a long time to write a book. More than one year per book so far. And I throw away a lot of scenes. Some of them are pretty good, but they just don’t serve the story. I’ve been feeling pretty lousy about how much of my first draft is landing in the trash pile, but reading about Sheldon’s process is making me feel better. (And thank goodness Scrivener saves all the Trash. I might get some use out of those discarded scenes one day.)

Funny you should mention this, Kay. I’m currently writing my next Romeo thriller, and felt there was something a bit bloated about the first act. There was a scene I really loved but it was holding things up. So I started a new Scrivener project, to be the Romeo following this one, and put the scene over there for safekeeping. Throw nothing away!

More Romeo?? Yay!

I put up my review of Romeo’s Rage and in it I practically begged you to write another one.

🙂

Your request shall be granted!

Great lessons for all writers, Jim. What a life Sidney Sheldon had, in facing suicide as a teen, working on the stage, in Hollywood, and later as a novelist, right up until his death. The passion of story shines through in the opening of his memoir. The opening chapter grabbed me from the get-go and had to buy the Kindle version as soon as I read it.

I remember, even late his life, that some colleagues and patrons at my library regarded his books as potboilers, even trashy, but he was still popular, still read. Any genre can be derided. The advice you shared from him is excellent, but I think another piece of wisdom by way of example from him as a writer is to be fearless in telling your stories. Tell them with passion, with craft, with persistence, aiming for the folks who will love those cliffhangers, and love those characters with the tangled webs they find themselves in.

Thanks for today’s post–insightful and inspiring!

We can all learn from “potboilers.” They are popular for a reason. Then apply those lessons to our own work. Sheldon has a lot to teach us on that score.

So true! I also found a hardcover copy of that 1989 Writer’s Handbook with his essay in it, and saw the list of other authors and decided ten bucks was a bargain for the advice and insight in that volume 🙂

I will have more to share from that book in later posts. So leave it to me!

Thanks! Looking forward to it!

Meant to add, I’ll definitely leave that sharing to you. Looking forward to what you’ll share from it next 🙂

I also saw the hardcover of the 1989 Writer’s Handbook. It’s on the way to my house.

Thanks for introducing me to a fascinating and inspirational character. So much great advice, too.

My pleasure, MC.

Such an inspirational post today, Jim. I agree with all his advice (not his writing process, but you can’t argue with the results). I’ve always found it easier to leave off a writing session mid-scene. That way, you never start the day by staring at a blank screen. Works great.

I agree, Sue. It’s a great way to keep up the momentum.

Thanks, Jim, for a very interesting and inspiring post. Like others here, I remember him from television (The Patty Duke Show and I Dream of Jeannie).

His advice and tips on writing are excellent, sound like much of what we discuss here at TKZ day after day, and remind me of another famous writer – some guy who wrote Plot and Structure.

Thanks for the link to Sheldon’s memoir. The breadth of his work – stage, TV, and books – is amazing.

As long as we put “famous” in quotes, Steve! I still have about 399 million copies to go to catch up with him!

Yes, an amazing career. I highly recommend The Bachelor and the Bobby-Soxer. One of my all-time favorite screwball comedies.

What a talent. I didn’t know he did I Dream of Jeannie.

Rage of Angels was my beach book one summer. I thought at the time I’d love to write a book that was as unputdownable as that one. It was wild.

I love to write screenplays because I want to see my work live on the screen, but there’s a lot to be said for the freedom a book gives you.

I think doing theatre gives you an ear for dialogue.

I envy the older writers. They didn’t let anyone tell them they had to have an MFA. They wrote across genres. It’s so pigeonholey today.

Cynthia, being trained as a screenwriter really helped Sheldon the novelist. His books are cinematic, and that’s something we all need to strive for. We’re such a visual culture now.

The stopping in mid-sentence bit never worked for me. I’d look at it the next day, say “where the heck is this going?” then I’d delete it and start over.

Reading so many famous writers’ methods of working, I’ve decided there’s a third type of writer. Neither a true outliner or a pantster, but an instinctive writer– one who knows their craft, characters, and the intricacies of plot so well that they can write without a map but know instinctively where they are going.

Stephen King does this, but he doesn’t understand that this comes from a place of knowledge, and he thinks every newbie should do this the same way. This attitude about writing is the main reason I don’t recommend his ON WRITING to newbies.

Plus, Sheldon’s work on plays and screenplays cemented structure in his brain. Same for Lee Child, who was in TV for a long time before turning to fiction.

I’m a little disappointed, Marilynn. Neither King, I, nor anyone else who advocates writing without rules says writers should ever stop learning. Not one of us advocate not learning the craft. Rather, we advocate that you can’t learn it by hovering over one work for weeks or months. Better to actually practice by putting new words on the page.

We advocate writing to the best of our current skill level, publishing, and then writing some more (with reading and learning in between). And yes, that’s for all writers who have a basic understanding of grammar and syntax.

The first reviewer of my very first novel, which I wrote in 28 consecutive days, wrote that it was “Among the most tightly plotted novels I’ve ever read.”

Those who want to follow the traditional process (outline, [write], revise, workshop, rewrite, polish, and finally submit or publish), should go at it by all means. At least “write” got squeezed in there somehwere. (grin)

But I’m no exception. I used to do all that. In fact, I spent three years outlining a novel that I guess I thought would be my magnum opus or something. Today, with almost 80 novels and novellas (as well as over 200 short stories) in my IP inventory, I still have never written that particular novel.

But learning to trust what my subconscious has absorbed about Story and trusting my characters to convey the story that they, not I, are living is freeing like nothing I’ve ever seen before. So natually I recommend this non-process and hope others will try it. But strictly for their own good, not mine. I get nothing out of it.

Of course, every writer is different. For anyone who would rather slave away over a hot stove all day to construct a story or novel and then complain about what terrible drudgery writing fiction is or at the least what hard work it is, they can have at it. Won’t slow me down at all or lessen my fun in the slightest. 🙂

What an inspiring story. He has much to teach us.

I too will have to track down a copy of his The Writers’ Handbook.

I seem to be selling a lot of those today. The greater part of the book is about markets for 1989. The majority of the magazines mentioned are no longer in existence, not to mention the publishing houses.

Remember SASEs?

When I speak to writing groups and mention SASEs I get the most puzzling looks. I remember reading Sidney Sheldon’s books when I was a wee lass (ha!) and I couldn’t put them down. Thank you for delving into his work and bringing us such timeless advice!

The youngsters ask, “What’s an envelope?”

Thanks for this, it’s a reminder that comes at a timely moment for me, especially as someone who also deals with bipolar disorder. I’ve read several of Sheldon’s books and the plotting and pace are amazing. I didn’t know the connection to The Bachelor and the Bobby-Soxer, despite it being one of my favorite movies.

Much like Sheldon, I’ve found that writing helps me tremendously. It’s almost like a drug and when I find myself unable to write I flounder. His “rules” are golden, and I try to follow them in all of my books

Thanks again!

My pleasure, David!