So many established authors stand before the collective body of the aspiring to offer up their “process,” and often it includes things like taking a walk, taking a nap, kicking the story around with a friend over beers, downing those beers alone and in abundance, jotting down our dreams, listening to voices in your head, or simply starting your story without a clue about what the ending will be, do it like Author X does it… all these among many other options.

Too often – not always, but sometimes – that seemingly credible information, under the guise of advice, is not what it seems.

Too often these anecdotal truisms are an author’s attempt to explain how good stories are hatched and developed, when in fact they simply can’t. So they imbue a description of their process – what they’d like you to believe about it – with mysterious and romantic little myths instead.

When the name behind these processes is well known, we attach credibility. And with a much higher level of risk, we attempt to cull meaning and clarity from what is spoken with the unshakable confidence of one who has been there.

Much of the time what you are hearing is a lie. Why?

Because it is only half the story.

The other half – you’ll almost certainly fail, or at least take years to get there, if you write your story without a solid grasp of craft, including structure… which the person telling you that half-truth usually does have going for them – awaits elsewhere.

They leave out the other half, the craft half, because they prefer to describe a catalyst and a means of accessing it, rather than the less adventurous advice of honoring and implementing it.

And thus, the “it” of the proposition remains unspoken.

Truth is, many of those famous names take years to write their novels. They may write 22 drafts (what they’re not saying is that they do this because they can’t seem to nail it with anything less, which is the exact opposite of an astute or informed process). Others are beaten down by their own process to an extent they can’t actually describe it truthfully.

And even if they could. many would choose to contrive a transparent case of inverted hubris, as if they simply submit to a muse, who is, of course, a genius. It sounds so heroic to appear humbly clueless and nonetheless have a New York Times bestseller on your hands.

You’ve probably heard these before:

“I never outline anything. That takes the creative fun out of it.”

“I just start writing and allow my characters to take over.”

“I don’t know how my story will end when I start a story.”

“I just do wherever the story takes me.”

“I can’t wait to get to my office every morning to see what my characters will do today.”

“I don’t write until I have every scene clearly stated on an index card.”

“There’s only three things that matter: a beginning, a middle and an end.”

“I often lose my story in the middle, and don’t know where to take it from there.”

“The best writing advice I can give you is this: just write. Butt in chair, that’s all you need to know.”

Keynote or interview zingers imbued with half-truths. All of them.

And yet, each of these has an unspoken explanation that comes next, but somehow rarely makes it into the speech or interview. Why? Because…

Some writers don’t really understand how it happened.

Chances are, as an analogous example, Phil Michelson’s coach can explain the perfectly executed physics of his golf swing better than Phil Michelson can. Apply that to famous writers and you now understand why they say the half-valid things they do.

All they do know is how it happened, rather than why it happened. To frame such halfisms as universal truth is risky, and often toxic.

And we, sitting in the audience or reading the article, are the target of that virus.

The only real truth here is that all of these things are valid… for them.

Hear that clearly. Because to assume their process, complete with 22 drafts and five years of listening for the voices of characters that exist in no other realm than in their head… to assume this thinking is valid for you, too, simply because someone else who you feel is further down the road than you has stated it emphatically, said it with an unimpeachable smugness…

… to internalize these as absolute truths as you own…

… just might be the very thing that is holding you back.

Because for every writer that these holy avowals actually help, there are stadiums full of other writers who try them and find themselves totally lost and irretrievably confused as a result.

Because, pure and simple, they don’t know what (for example, this being a writer who advises us to just write) Stephen King knows.

Which in the real world means: you shouldn’t try to do it the way Stephen King or Diana Gabaldon does it… until you do know what they know.

Process is the outcome of what you understand, and what you don’t.

That’s a loaded sentence, one that can clear the air of any confusion you may have about your process. Read it again, and pay close attention to that single italicized word.

Everyone, every single author who uttered those quotes you see above, as well as the long list of other process-relevant advice and truth you’ll ever encounter out there, and here on this blog, and on my website, and in every writing conference keynote you’ll ever hear twenty minutes before you stand in line to get that author’s autograph on the novel that is the outcome of the process they’ve just offer up…

… for them and for me and for you… the truth is… all of it is an attempt to describe the means by which they are searching for the story.

And – this being a truly unassailable fact – there is no right or wrong way to go about that.

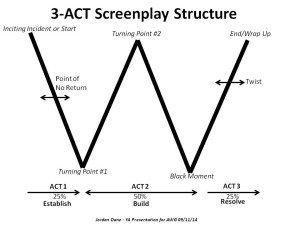

Process always has two major parts:

First, we must find our best story for our premise. Sometimes continue to search for and evolve the premise itself before that best story can emerge. Sometimes that takes five years, sometimes it doesn’t.

For many this search happens with a series of drafts, for others the use of notes leading to an outline. Both processes strive for the exact same thing, with the exact same criteria defining the outcome.

And then, once we have the story in hand, we must develop and execute it across the entire arc of the narrative, which (as professionals know) is not a structure we simply get to make up as we go. Again, this involves drafts and/or outlines, both of which evolve as the process continues.

Here’s where trouble ensues: when a writer doesn’t recognize where they are relative to those two parts, and when they merge them without the craft-based skill to do so.

And then, without that best premise in hand, they finish a draft and submit nonetheless.

The result: rejection. Which, upon a competent post-mortum, leads back to that moment they decided they had found their best story, instead of soldiering onward in search mode.

And for some, even when they do find their best premise, they don’t really understand how to spool it out across the dramatic arc of the story… so they wing it, in essence trying to invent a structure that is, inevitably, already waiting for them within a true understanding of craft.

Stories fail for two reasons, not always connected: the premise isn’t strong enough, and/or the execution isn’t good enough.

The universal writing conversation rarely cuts through the experiential muck to shine a light on what’s really happening in that regard.

Everyone, no matter how they do it, engages in the search for story phase, the outcome of which determines the quality and power of the story the writer believes they have found.

Sadly, because the writer doesn’t know better, a chosen process itself can compromise the story; again, because of what you think you know (but is off-the-mark), possibly because you read it an interview (which was only half-true)… or don’t know at all.

If the story development process it too painful, too long, too confused by a lack of clarity about what you are actually searching for… if your process is to head down one narrative road and then, when you encounter serious issues, simply take a turn rather than going to square one, resulting in a story that is nothing other than a series of compensating, written-in-the-dark turns that, at the end of day, make too little sense…

… all of it in context to nothing more than your experience as a reader of novels, rather than as a student of storytelling and structural craft…

… if your process doesn’t serve you, then your process is the problem.

And yet, writers cling to their process like a religious ideology.

Ultimately it isn’t about what you believe… it is about what is true.

What remains unspoken in this conversation is something that resides at the center of any and every process, fueling it and defining it. It is craft, broken down into a list of principles, criteria and benchmarks. Your awareness of this is the very thing that eventually makes a process right or wrong for you.

And surprisingly, it is accessible, learnable and even measurable.

What every single one of those authors who end up behind a dais at a keynote knows, in one form or another, even if they cannot articulate it (and many can’t)… is some sense of the criteria, benchmarks and metrics of the craft storytelling.

Muses, by the way, in any form, have no idea about that. Craft is our contribution to the process, one that must be learned and earned, no matter how the story idea arrives.

With this dirty little secret in place, it all boils down to a question of informed preference relative to our chosen process. Again, with an emphasis on that single italicized word.

If you don’t fully understand the things you need to know about storytelling, then your process doesn’t matter, you’ll struggle and end up re-doing and revising and starting over and over… until one of two things happen: your revisions bring the story to a closer alignment with those standards… or, you begin to grasp what is wrong and what is missing – the essence of craft itself – and then apply that new awareness to the work.

So by all means, listen to other authors.

Pay attention to all of it. Much of the bluster – “I never outline!” – comes from writers with no more experience or credibility than you. Just know this: they may or may not be describing a valid process… for you.

Suffering is optional. If your goal is to publish successfully, an ownership of the principles of storytelling craft is not.

Just be careful about who and what you believe about it.

*****

Larry’s new writing craft book, “Story Fix: Transform Your Story From Broken To Brilliant,” is now available for Kindle on Amazon.com, and at this writing is the #1 bestseller in the Editing category. (The trade paperback edition releases in October, but can be pre-ordered now.)