Another brave writer submitted their first page for critique. My comments/suggestions will follow. Enjoy!

Expendable

Prologue

Kate turned right onto her parent’s street only to find a street jammed with police cars. A cacophony of lights, flashing red and blue, backlighting people hurriedly moving against the night sky. My parents will certainly be outside watching, she thought. As she drew closer, she was alarmed to see her parent’s house isolated by swags of yellow police tape.

She jerked her car to the curb and ran toward the chaos.

“I’m sorry, miss. You can’t go up there.” A policeman seemed to appear out of nowhere.

“But, I live here,” she lied.

“This is your house, miss?”

“It’s my parents’ house. I live with them. Please let me through.”

“I’m sorry, ma’am. You can’t go up there.” The officer blocked her path and motioned to a man in an overcoat, standing near the garage. The man closed his notepad as he walked over. The two men had a brief exchange before the one in the overcoat spoke.

“Miss, my name is Detective Montoya.” A badge swung on a ball-chain around his neck. “You live here?” he said, opening the notepad again. She nodded. He put his hand on her shoulder, guiding her to a place on the lawn, away from the activity. He began writing as soon as she answered. Asked her name along with a few other questions. She gave terse answers, anxious to get inside. He asked whereabouts that evening requiring a lengthy explanation about her late class on Wednesdays. Each answer seemed to beget another question.

“Miss, what we’re looking at here is a double homocide. We’re still investigating.” Twenty-seven years as a cop told him it was likely her parents but kept it to himself.

“No,” she said, covering her mouth with both hands. She battled her mind to keep from considering the obvious. “That’s impossible. No, it can’t be. Let me see,” she tried to force her way past him.

“I can’t let you in. It’s pretty gruesome. I don’t know that you could handle it.”

“I need to go inside.”

“I’m afraid you can’t, miss. Right now, it’s a crime scene and we can’t take the chance of you contaminating it.”

“Look,” She said. “You owe me something. You can’t ask me to endure the entire night wondering if I’m still part of a family or not.” Instinct told him to say no but she had a point.

The writer did so many things right. We’re dropped in the middle of a disturbance, s/he raised story questions, added relatability for the heroine, and I could (somewhat) feel her frustration, fear, and anxiety. Great job, Brave Writer! As written, I’d turn the page to find out what happens next.

Let’s see if we can improve this opener even more. Brave Writer included a note about using a prologue. I hope s/he doesn’t mind if I include it here.

I have never considered doing a prologue before but this allows me to describe a major event that will be referred to various times during the story as well as give some backstory about the protagonist and tell the reader what kind of story to expect.

Prologues

The correct reasons to use a prologue are:

- the incident occurs at a different time and/or place from the main storyline

- to inform the reader of something they can’t glean from the plot

- to foreshadow future events (called a jump cut, where we use the prologue to setup an important milestone in the plot)

- to provide a quick-and-dirty glimpse of important background information without the need of flashbacks, dialogue, or memories that interrupt the action later on (no info dumps!).

- Hook the reader into the action right away while raising story questions relevant to the main plot, so the reader’s eager to learn the answers.

It sounds like you’re using a prologue for the right reasons. Keep in mind, if you plan to go the traditional route, many agents and editors cringe when they see the word “prologue” because so many new writers don’t use them correctly. If you can change it to Chapter One, you’d have an easier time.

Point of View

For most of the opener you stayed inside the MC’s head.

Two little slips:

“Miss, what we’re looking at here is a double homocide homicide. We’re still investigating.” Twenty-seven years as a cop told him it was likely her parents but kept it to himself.

See how you jumped inside the cop’s head?

Same thing happened here:

Instinct told him to say no but she had a point.

Stay inside the MC’s head. One scene = one point of view.

Dialogue

The dialogue is a bit stiff. I’ll show you what I mean in the “fine tuning” section. For now, I highly recommend How To Write Dazzling Dialogue by our very own James Scott Bell.

First Lines

There’s nothing particularly wrong with the first line, but I think you’ve got the writing chops to do even better. Let the first line slap the reader into paying attention.

To quote Kris (PJ Parrish):

- Your opening line gives you an intellectual line of credit from the reader. The reader unconsciously commits: “That line was so damn good, I’m in for the next 50 pages.”

- A good opening line is lean and mean and assertive. No junk language or words.

- A good opening line is a promise, or a question, or an unproven idea. It says something interesting. It is a stone in our shoe that we cannot shake.

- BUT: if it feels contrived or overly cute, you will lose the reader. Especially if what follows does not measure up. It is a teaser, not an end to itself.

“The cat sat on the mat is not the opening of a plot. The cat sat on the dog’s mat is.” – John LeCarre

To read the entire post, The Dos and Don’ts of a Great First Chapter, go here.

Fine Tuning

I dislike rewriting another writer’s work, but it’s the easiest way to learn. I’ve included quick examples of how to tighten your writing and make the scene more visceral. Keep what resonates with you. After all, I don’t know where the story is headed.

Kate turned right onto her parent’s street only to find a street jammed with police cars. A cacophony of lights, flashing red and blue, backlighting people hurriedly moving against the night sky. My parents will certainly be outside watching, she thought. “Thought” is a telling word. The italics tell the reader it’s inner dialogue. As she drew closer, she was alarmed to see her parent’s house isolated by swags of yellow police tape. “Alarmed” and “see” are also telling words. Remember, if we wouldn’t think it, our POV character shouldn’t either. Some writers have a difficult time with deep POV, which we’ve discussed before on TKZ. It’s one element of craft that we learn at our own pace. For more on Deep POV, read this 1st page critique. In the meantime, here’s a quick example to show you what I mean.

The swags of yellow police tape surrounding her parent’s house quickened her heartbeat. What happened? She’d spoken to Mom and Dad last night. Granted, the call didn’t last long. Mom said she had to go because someone knocked at the door. Endless questions whirled through her mind. Were they robbed? Are they hurt? Did Dad fall again?

She jerked her car to the curb, threw the shifter into Park, and ran sprinted toward the chaos, the soles of sneakers slapping the pavement. Use strong action verbs to paint a clearer mental image. Plus, I slipped in sound. With important scenes, tickle the senses—sight, sound, touch, smell, taste—for a more visceral experience.

A policeman seemed to appeared out of nowhere. Moved to the beginning to show who’s speaking. Here, too, you can paint a stronger picture: A meaty-chested cop blocked her path. “I’m Sorry, miss, but you can’t go past the police tape.”

“But, I live here,” she lied. Not bad but think about this: She’s just happened upon a chaotic scene at her parents’ house. Would she be calm or hysterical? “Get the hell outta my way.” She swerved around him, but he hooked her arm. “I live here.”

His head jerked back. “This is your house, miss?”

“It’s my parents’ house. What’s the difference? I live with them. Please Let me through!”

“I’m sorry, ma’am. Sorry, but you can’t go up there.” Is the house on a hill? If so, you need to tell us sooner so “up there” makes sense. The officer hollered over his shoulder to blocked her path and motioned to a man in an overcoat (trench coat?), standing near the garage. “She’s the daughter.” The man closed his notepad as he walked over. The two men had a brief exchange before the one in the overcoat spoke.

Mr. Trench Coat hustled over, a badge bouncing on the chain around his neck. As he neared, he extended his hand, but she couldn’t shake it. Not yet. Not without knowing what happened. “Miss, My name is Detective Montoya. And you are?”

“[Insert her name]” Now the reader knows who she is.

“Okay, [name]. Let’s talk in private.” He put clamped a his hand on her shoulder and guided, guiding her to a place on to the lawn, away from the activity. Describe the activity. Example: away from photographers snapping pictures, from uniformed officers guarding the front door, from men and women in white coveralls strolling in and out with evidence bags.

A badge swung on a ball-chain around his neck. “Do you live here?” he said, opening the notepad again.

Tears rose in her throat, and she could only nod.

He began writing as soon as she answered. Asked her name along with a few other questions. The detective would hold her gaze. She’s the daughter of two murder victims and he needs as much information as possible before he breaks the news.

She gave terse answers, anxious to get inside. Don’t tell us. Show us!

He asked whereabouts that evening requiring a lengthy explanation about her late class on Wednesdays. Each answer seemed to beget another question. Don’t tell us. Show us!

“Miss (since he knows her name, he wouldn’t call her miss), what we’re looking at here is a double homicide homicide. We’re still investigating.” Twenty-seven years as a cop told him it was likely her parents but kept it to himself. This dialogue doesn’t ring true. A detective would try to avoid telling her about her parents until she forces him to, which gives you the perfect opportunity to add more conflict through dialogue.

Example:

“When’s the last time you spoke to your parents?”

“I dunno. Before I went to class, around eight. Why?”

“Did they mention anything unusual? A strange car or someone they didn’t recognize hanging around the neighborhood?”

“What? Why? Are my parents okay?”

“Did they meet anyone new recently?”

“Are they in the ambulance?” She peeked around him, but he stepped to the side to block her view. “Look. I’m done answering questions. Get outta my way.”

“[Name], I’m sorry to inform you, your parents…” His words trailed off, his voice muffled by the ringing in her ears.

“No.” Head wagging, she slapped her hands over covering her mouth with both hands. She battled her mind to keep from considering the obvious. What’s the obvious? Do you mean, the truth? Also, “considering” is a telling word. “No. What you’re saying isn’t That’s impossible. I just spoke to them. I’ll prove it to you. it can’t be. Let me see,” She tried to force her way past him. Don’t tell us. Show us! Example: She shoved him away, but he wrangled her flailing arms, pinned her wrists to her side.

“I can’t let you in. It’s an active crime scene now. pretty gruesome. I don’t know that you could handle it.” A detective would never tell the daughter of two murder victims that “it’s pretty gruesome,” nor would he even consider allowing her into an active crime scene whether “she could handle it” or not.

Instead, show us what’s happening around her. Example: The coroner’s van sped into the driveway. Two men dragged a stretcher from the back.

Our heroine entered a chaotic scene. She’d be on information overload, with sights, sounds, smells all around her, almost too much to process.

“Please.” She waved praying hands, her chest heaving with each hard breath, tears streaming over her cheekbones. “Please let me see them. Please.. go inside.”

“C’mon, let’s get you out of here.”

“I’m afraid you can’t, miss. Right now, it’s a crime scene and we can’t take the chance of you contaminating it.”

“Look.” she said. Remove tag. We know who’s speaking. She stomped the grass. “You owe me something kind of explanation. What happened to my mom and dad? Who did this?” You can’t ask me to endure the entire night wondering if I’m still part of a family or not.” Instinct told him to say no but she had a point.

Wrap it up soon. Prologues should be short. Unless, of course, you decide to make this Chapter One. 🙂

Brave Writer, I nitpick the most promising first pages because I know you can write and write well. If I thought otherwise, you’d see a lot less red. 😉 You’ve given us a compelling opener and plenty of reasons to turn the page. Take a few moments to see the forest for the trees. The elements I’ve focused on are meant to enhance your storytelling abilities. So, yell, scream, curse me, then get back to work. You’ve got this. Great job!

Over to you, TKZers. How might you improve this first page?

Side note: I won’t be around today. What I’m doing is super exciting (!!!), but I’m not at liberty to speak publicly about it yet. Fill you in later…

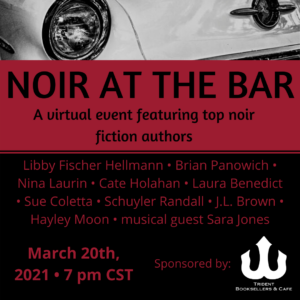

Join me, Laura Benedict, and many others on Zoom for Noir at the Bar. Win a signed paperback in the giveaway!

Join me, Laura Benedict, and many others on Zoom for Noir at the Bar. Win a signed paperback in the giveaway!

When: Sat., March 20, 2021

Time: 7 pm CST/8pm EDT

Tickets are FREE (limited to the 1st 100 fans)

Where: Comfort of home

Register: http://noiratthebar.online

Join me, Laura Benedict, and many others on Zoom for Noir at the Bar.

Join me, Laura Benedict, and many others on Zoom for Noir at the Bar.

Another brave writer submitted their first page for critique. My comments will follow.

Another brave writer submitted their first page for critique. My comments will follow.