I came across this post recently and found it exceptional advice for all those struggling to construct a synopsis. So I contacted the author, Mike Wells, and invited him to guest blog today and share his insight into what some writers feel is one of the hardest tasks an author must address. Join me in welcoming Mike. Read on, learn and enjoy. Joe Moore

————————————————

If you’re like most authors, summarizing your book in a couple of sentences is a daunting task. However, if you’re going to sell your book, it’s simply something you have to do. If you choose to go the traditional route, agents and editors alike are bombarded  with so many queries that if they find themselves having to do much mental work to understand the gist of your book, they will simply pass on to the next one. The same goes for self-publishing–all the retailers and distributors require short descriptions of your book. For example, Smashwords requires a description that can be no more than 400 characters, including spaces! That’s short, folks!

with so many queries that if they find themselves having to do much mental work to understand the gist of your book, they will simply pass on to the next one. The same goes for self-publishing–all the retailers and distributors require short descriptions of your book. For example, Smashwords requires a description that can be no more than 400 characters, including spaces! That’s short, folks!

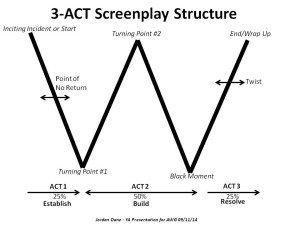

To help you do this, I want to share a formula I learned a long time ago, one that was created in Hollywood. I can tell you from my dealings with the people in the movie industry that when it comes to stories and story structure, they really know their stuff.

Each and every story is composed of the same five basic elements. If you can identify them in their purest, simplest forms, you will be well on your way to writing a good two-sentence synopsis of your book, regardless of its length or complexity.

The five elements are: a (1) hero who finds himself stuck in a (2) situation from which he wants to free himself by achieving a (3) goal. However, there is a (4) villain who wants to stop him from this, and if he’s successful, will cause the hero to experience a (5) disaster.

Actually, what I’ve just written above IS the two sentence synopsis which will work for any story, no matter how complex the plot or characters may seem.

Before I go further, I want to stop for a moment and address the “Is this a formula?” question that will undoubtedly come up in many writers’ minds. Anyone with any experience in writing (or painting or composing music, etc.) knows that formulas do not work when creating a new piece of art, that the most you can hope for is a cookie-cutter type result that will be mediocre, at best.

However, what we are doing here is summarizing a piece of art that has already been created. Because we know that each and every story must contain these five elements, if we can step back from our own story and identify them, it makes the job of summarizing the story much easier.

The only thing formulaic about this approach is the order in which the information is presented, and the structure of the sentences. You can change this around later and make the synopsis appear as original and unique as you desire.

So, back to the method. Another way to write this compressed synopsis is to move the goal into the second sentence into the form of a question, as follows:

Hero finds herself stuck in situation from which she wants to free herself. Can she achieve goal, or will villain stop her and cause her to experience disaster?

All you have to do is identify the elements and plug them in to create the most basic two sentence synopsis for your own story. By the way, you don’t have to put the second sentence in the form of a question–you could write, She must achieve goal, or villain will stop her and cause her to experience disaster. I posed it as a question only because it emphasizes the main narrative question in the story–discovering the answer to that sticky issue is what keeps readers turning the pages until (hopefully) they reach the very end of your book.

The best way to demonstrate the process of creating a two-sentence synopsis is with a real example. As virtually everyone knows the story of The Wizard of Oz, let’s use that. The five elements are:

HERO Dorothy, a Kansas farm girl

SITUATION Finds herself transported to faraway land called Oz.

GOAL To find her way back to Kansas

VILLAIN The witch

DISASTER To be stuck in Oz forever

Plugging the elements into the two-sentence structure, we have:

Dorothy, a farm girl, finds herself transported to a faraway land called Oz. Will the witch kill her before she can find her way back to Kansas?

Now, before you begin to think that this sounds too simplistic for your story, or if you don’t believe your book contains one on more of these elements, or that they seem too melodramatic, etc.–you’re wrong. Your story has all five elements, or it would not be a story.

Your story must have a hero, even if that hero happens to be a cat. And your hero must be stuck in an untenable situation and develop a goal to escape that situation, or you have nothing but a character study, not a story. The untenable situation could be something as mundane as boredom or as abstract as a blocked unconscious need to act out rebelliousness. But that untenable situation is there, and the hero must have a goal to escape it. Furthermore, if there is nothing to stop the hero from achieving her goal (i.e., a villain), then you have no conflict. No conflict, no story.

Granted, some of your story elements may require some thought to identify. For example, your villain might be society as a whole, Mother Nature, or even your hero’s self-doubt. Similarly, your disaster could be little more than your hero having to live with an unbearable self-concept or overwhelming guilt. It’s also important to remember that the “disaster” is seen through the eyes of the hero. This is usually the worst possible scenario he or she can envision at the beginning of the story, but may in fact be the just outcome, or the outcome that does the hero the most good in the long run.

Back to The Wizard of Oz. While the two sentence synopsis we wrote is accurate, it is also painfully dull. This because we started with the five story elements distilled into their absolute minimal forms (done intentionally by me for the purpose of this exercise). To jazz it up, let’s go through the list and expand each element:

HERO – Dorothy isn’t just a farm girl, she’s a lonely, wistful farm girl

SITUATION – Dorothy isn’t merely transported to Oz, but is whisked away by a tornado and dropped there. Also, Oz is far more than a faraway land, it’s a magical but frightening place, full of strange characters, little people call Munchkins and witches, both “good” and “bad.”

GOAL – Dorothy’s main goal is to get back to Kansas, but she soon learns that only the great and powerful Wizard of Oz can help her do that, and he lives in Emerald City, a long and dangerous journey from her starting point (You’ll note that in any story, the hero’s main goal breaks down into a series of sub-goals).

VILLAIN – The witch is more than “just a witch”–she is the Wicked Witch of the West.

DISASTER – Dorothy’s possible fate is actually worse than being stuck in Oz forever–the Wicked Witch of the West is determined to kill her.

So, let’s plug these expanded elements into the original formula.

Dorothy, a lonely, wistful farm girl, is whisked away by a tornado and dropped into in a faraway land called Oz, a magical but frightening place, filled with strange and wonderful characters–little people called Munchkins, and witches that are both good and bad. Can Dorothy make the long and dangerous journey to Emerald City to see the Wizard, the only one who can help her return to Kansas, or will the Wicked Witch of the West kill her first?

Note that we still have exactly the same structure as before which does make the synopsis read a bit clumsily. But you have to admit it’s a lot more colorful and engaging. For better reading flow, the first sentence can be rearranged as follows:

When a tornado strikes her home in Kansas, a lonely, wistful farm girl named Dorothy finds herself transported to a faraway land called Oz, a magical but frightening place, filled with strange and wonderful characters–little people called Munchkins, and witches that are both good and bad. Can Dorothy make the long and dangerous journey to Emerald City to see the Wizard, the only one who can help her return to Kansas, or will the Wicked Witch of the West kill her first?

Once you have this much, you can keep expanding, rearranging, and enriching the synopsis to make it as long and original-sounding as you like. You can pull in more information–for example, that Dorothy’s house fell on the Wicked Witch of the East (which sets up the motivation of why the Wicked which of the West loathes Dorothy, as the two witches were sisters), and you can break the main goal down into sub-goals (for example, that Dorothy is only told that she must “follow the Yellow Brick Road” to reach Emerald City, and that once she does manage to see the Wizard, he tells her she must bring him the Wicked Witch’s broom in order to prove her worthiness, and so on)

In my query letters, I always include a two sentence synopsis similar to that above in terms of detail, then usually expand on it in another paragraph and introduce more subtle elements. In this second paragraph, I always try to point out the villain’s motivation to stop the hero (as above) and also the most important character conflict. Although I did not do this above for The Wizard of Oz, the most important character conflict in that story might be between Dorothy and the wizard–after she does manage to return with the witch’s broom, he gives her the runaround, and she must find the courage within herself to stand up to him and demand that he deliver on his promise.

The two-sentence synopsis method takes a little practice, but once you get the hang of it, you will find the task of writing synopses–of any length–much easier. In fact, now I often write this type of two-sentence synopsis as soon as my story idea has jelled, because the “top down” approach helps me stay focused as I begin the actual process of putting it into words.

One word of caution: if you are having trouble generating interest in your book, resist the urge to “reposition” the story to make it more appealing to agents who represent other genres. For example, if you had written The Wizard of Oz and could not get any fantasy genre agents to read it, you could compose the following short synopsis to make it into an edgy thriller:

Transported to a surreal landscape, a young girl kills the first person she meets, then teams up with three total strangers to kill again.

I’m joking, of course, but you get the idea. Such repositioning misleads agents and wastes their time.

To see the two-sentence synopsis method applied to ten different well-known stories from literature and film, go to Story Synopsis Quiz. All ten of these synopses are written in exactly the same form as I have outlined here. To practice, you might try writing up a few from your favorite books, plays and films.

———————————

With 30 years experience as an author. I strive to create the most engaging, entertaining, well-written novels that I can. My goal is to take you to places you have never been, and to keep you anxiously turning the pages, always asking for more. I hope you enjoy my books! Be sure to visit my blog at http://mikewellsblog.blogspot.com/

The Last Victim coming Oct 30, 2015 in print and ebook. Available for ebook preorder through Amazon Kindle at a discounted price.

The Last Victim coming Oct 30, 2015 in print and ebook. Available for ebook preorder through Amazon Kindle at a discounted price.