Today I welcome my friend and fellow ITW member Brad Parks as our guest blogger. Brad takes on one of the most elusive yet essential elements in successful storytelling. Read on to find the answer.

—————————–

Once upon a writer’s conference, a friend of mine—who might or might not be Chantelle Aimee Osman, depending on how she feels about being described as my friend—was going around, asking folks a great question:

In Hollywood, people talk about certain actors or actresses having an “It Factor,” that special something that just draws in the eye and won’t let it go. Is there an It Factor with writing; and, if so, what is It?

I answered with one word: Voice.

Voice, I will posit, is the writing equivalent of a killer body, great hair and a mysteriously alluring smile.

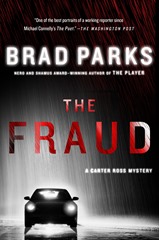

And while I volunteered to take this guest blog spot from Joe because I have a new book to  flog—it’s called THE FRAUD, and when I’m flattering myself I think it’s a fine example of a healthy narrative voice—I want to take a few minutes of your blog time to unpack this subject, because it strikes me as one that folks in the writeosphere don’t spend enough time discussing.

flog—it’s called THE FRAUD, and when I’m flattering myself I think it’s a fine example of a healthy narrative voice—I want to take a few minutes of your blog time to unpack this subject, because it strikes me as one that folks in the writeosphere don’t spend enough time discussing.

Which is strange. Ask any editor or agent what they’re looking for in a manuscript, and a strong, fresh, unique voice is inevitably at or near the top of that list. The same is true for readers, even if they might not be able to articulate it as such.

The proof can be found at the top of the bestseller list. I’m willing to bet I could kidnap you, drag you into the desert, beat you with sage brush and leave you to die in the brutal sun; but, if before I departed, I also left you with a stripped paperback that began…

I was arrest in Eno’s Diner. At twelve o’clock. I was eating eggs and drinking coffee. A late breakfast, not lunch. I was wet and tired after a long walk in heavy rain. All the way from the highway to the edge of town.

… you’d be like, “Oh, cool. Reacher.” (Or at least you would if you were a Lee Child fan, as I am).

Many of the writers whose book sales are counted in the millions have voices that are so distinct, you could wipe their names and all other identifying characteristics from their work, and yet most of us would still be able to identify their prose within a few paragraphs.

Think of Harlan Coben (where suburban suspense meets Borsht Belt shtick); or Sue Grafton (who couldn’t pick Kinsey’s chatter out of a crowd?); or James Lee Burke (you can hear Louisiana in everything that falls out of Robicheaux’s mouth); or Elmore Leonard, or Laura Lippman, or… or…

It starts with voice. And, yes, of course the writers I’ve listed do many other things well, whether it’s Coben’s great twists or Lippman’s great characters or what have you. But I would argue that voice also covers the things they don’t necessarily do well. Because when a writer has a strong voice? The reader is already buckled in, happy to be along for the ride.

This is great news for all of us who attempt to prod words into compliance. Because unlike Hollywood, where the It Factor is at least partially based on things you have to be born with—some marriage of facial symmetry, bone structure, and that certain crinkle around the eyes—voice is something that can be developed.

Let’s start from 30,000 feet up, with a simple definition of what it is we keyboard-ticklers do each day. Writing is nothing more than (and nothing less than) the task of transferring thoughts from your brain to paper.

It sounds simple enough, except when you start out, there’s this thick filter between your head and the page. And, depending on how tortured your formal education might have been—and how many misguided English teachers forced you to write keyhole-style essays or said you couldn’t end sentences in a preposition—the filter can stay thick for many years.

But if you keep working the writing muscle, the filter starts to thin out. The thoughts get to the page more readily than they did before. You start to notice little things that are dragging on your prose and you eliminate them. You read great writers and incorporate the things they do so well. You read your stuff out loud and develop an ear for what sounds clunky and what sounds cool.

Eventually, the filter disappears. Then it’s just you, in all your idiosyncratic genius. And if you accept that no two people’s thoughts are the same—yes, you really are that special snowflake—no two writers’ voices will be the same, either. Ergo, you will be that strong, fresh, unique voice that someone out there is looking for.

And, no, none of this happens particularly quickly. If you thought I was going to offer the equivalent of a miracle diet for writers—Lose 30 Pounds And Gain Your Voice In Two Easy Weeks, Guaranteed!—I’m sorry to report no such thing exists.

Personally? I started writing for my hometown newspaper when I was 14 years old and I didn’t start to develop a whimper of a voice until I was at least 19. Even then, it was probably just a subconscious imitation of the writers I admired. I didn’t start to have a voice of my own until I was probably 24. Well, okay, maybe 26.

Admittedly, I’m not the quickest study. I’m sure a brighter light could find their voice faster than I did. But, perhaps, only by a little. Writing is a journey without shortcuts, because the destination only becomes clear to you after you’ve arrived.

But at the end of this particular road, the voice—that It Factor—is waiting for you. Fact is, it’s been inside you all along, screaming to get out.

Brad Parks is the only author to have won the Shamus, Nero and Lefty Awards. His sixth thriller featuring investigative reporter Carter Ross released yesterday. For more, visit www.BradParksBooks.com.

Brad Parks is the only author to have won the Shamus, Nero and Lefty Awards. His sixth thriller featuring investigative reporter Carter Ross released yesterday. For more, visit www.BradParksBooks.com.

Great article. I particularly liked this, ” Writing is nothing more than (and nothing less than) the task of transferring thoughts from your brain to paper.” So simple, yet so true. Going to have to remember that one.

All the Best,

Matthew.

Thanks, Matthew. Good luck with your work!

Thanks. You too.

Brad! Baby! It’s me!

Amanda!

A M A N D A

Sure you remember me, your favourite Canadian stalker! What? Vaguely familiar? Sigh.

Anywho, great post. Very encouraging and written with your usual humour. I recognized The Killing Floor with the first sentence. It’s Child’s first Reacher book and the only one, I believe, written in the first person before switching to third.

That’s a lot of firsts.

I pre-ordered The Fraud months ago, just waiting for it to show up.

Hey Amanda! Great seeing you somewhere other than the bushes outside my house. And I see you’ve put down the telephoto lens. I think that’s very healthy. : )

Thanks for ordering the new book!

Lee Child usually seems to write Third Person, but he occasionally returns to First Person with his Reacher Novels. As well as Killing Floor, there’s Persuader, The Enemy, Gone Tomorrow, The Affair and Personal (books 7, 8, 13, 16 and 19) are in First Person, at least according to Wikipaedia.

With his Reacher Books I’m only up to The Visitor – Echo Burning is “burning” a hole in my bookcase waiting to be read. Die Trying is still my favourite though. I love the way that a single act of kindness (holding a door for a woman on crutches) spirals into Reacher being caught up in a huge plot with major consequences. I think it’s a great example of starting small and building to a big climax.

All the Best,

Matthew.

This should have been attached to Amanda’s post above, sorry.

I checked, Matthew, and you’re right! Not that I thought you’d lie to me but I figured it would be a good idea to confirm before I started ranting.

It’s interesting. First, because it didn’t seem to matter in what ‘person’ Child wrote (notice how I did not end that sentence with a preposition), when the new book landed on my doorstep I was just so darned excited to get reading, the whole ‘person’ thing slipped right by me; and second, because it seems so inconsistent…what’s the reason for the switching?; and third, because every agent I talk to (I know so many personally, lol), believe third person is the way to go.

I guess it depended on the story Mr. Child was telling.

I always think of the different voices–first, third, close third, omniscient third, etc–as being like different tools in a garden shed. Each has its advantages and constraints. You wouldn’t want to dig a hole with a rake anymore than you’d want to sweep up leaves with a shovel. The trick is picking the right one for the story you want to tell, and using the full advantages of the voice you’ve chosen. Lee probably does that as well as anyone.

I’ve seen a few authors use First and Third person in the same book and it turn out really well. In each case different characters were using a different POV, so you knew immediately which character you were following in this chapter just from the POV being used.

Brad, thanks for a great post.

Wonderful ideas on removing that filter between our brains and the page.

Your discussion gave me this thought: Playing with short stories, between novels, gives the writer more opportunities within a shorter span of time to experiment with voice. (see Kris and Kelly’s post from yesterday).

Thanks.

That’s a great point, Steve. Thanks for reading!

“But if you keep working the writing muscle, the filter starts to thin out.”

Absolutely! To continue the metaphor, I’m reminded of Arnold Schwarzenegger’s example. When he was just another iron-pumping lad, he idolized his hero Reg Park, who made scads of Hercules movies in the 50s. But as Arnold kept experimenting, trying new techniques, learning more about the body, and even taking dance lessons so his exhibitions flowed better, he finally transformed himself from Arnold the wannabe to ARNOLD.

And just to add – I think the more you work that writing muscle the more you feel confident about letting your own voice break free. Often writers feel they have to write a particular way to ‘sell’, forgetting that a fresh voice, a liberated voice, is what agents and editors are really looking for. It can be hard to gain that confidence and find your writer voice but it’s critical and often only comes after lots and lots of practice…but who said this was easy, right?!

Amen, Clare. Amen.

Welcome to TKZ, Brad! I love thinking about the writer’s voice. When I first started writing fiction, I wrote under contract for the Nancy Drew series, and getting the voice was simply an act of imitation. It took me years to develop a voice of my own for Kate Gallgher. Nowadays I’m writing paranormal suspense with an unreliable narrator. And again, finding the right voice is my main challenge.

Yeah, I feel like I can’t even start a piece until I have the voice in my head. Have you tried writing a short bit and then reading it aloud? I find that helps a ton.

Brad, thanks so much for stopping by TKZ and sharing your thoughts on the writer’s voice. Come back soon.

Thanks for having me on, Joe. I’ll try to stop by a few more times today in case there are more comments. But I’ve really enjoyed the discussion so far. Thanks everyone!

I couldn’t agree more. I recall meeting someone at an author talk I gave, and afterward, she approached me and said, “You write just like you talk.” My rule of thumb—if it sounds “writerly”, cut it. When the words flow from the fingertips, that’s probably your own voice coming through. Let it sing.