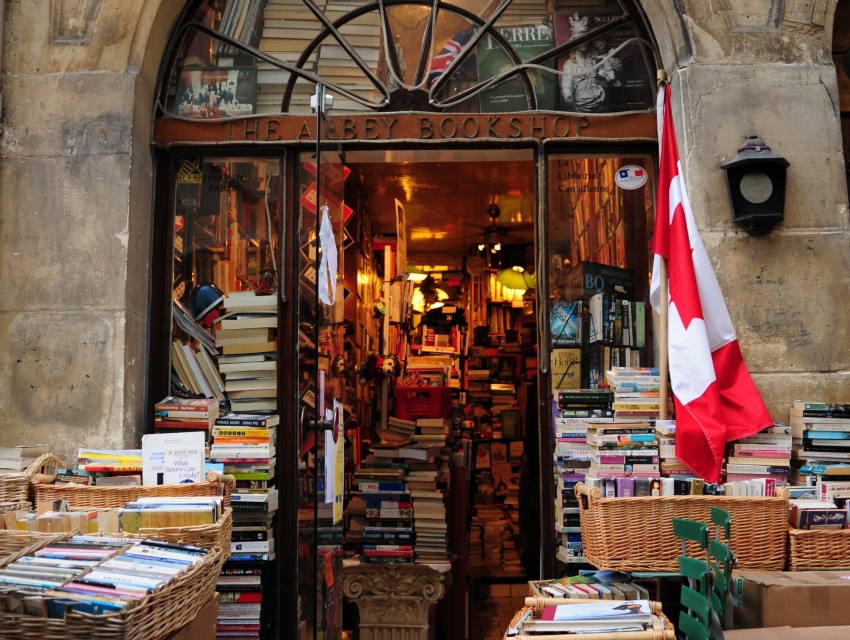

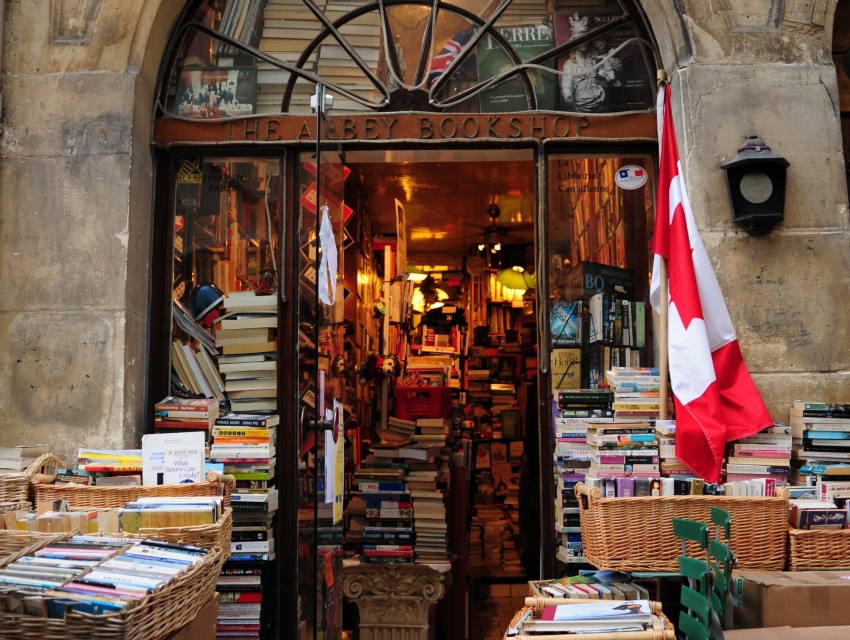

The Abbey Bookshop in Paris

Cars are not nouns. They’re adjectives. — Fredrik Backman

By PJ Parrish

The best thing about vacationing in a foreign country is not being able to understand what’s on television. During our month-long stay in France, I was limited to the reality show Master Chef in French. A deflated souffle is the same in any language — pack your knives, knave!

So I got to read. A lot. I don’t use Kindles or tablets so I have to rely on tree books. I took three but burned through them fast. Restocked at the Abbey Bookshop in Paris, but still ran out of good stuff by the time we got to Provence. Luckily, our rental house had bulging bookshelves. Unluckily, most of it was non-fiction or Italian novels. Including Stephen King’s L’Ombra dello Scorpione. (No clue…)

I read 22 books in three weeks. Some were as great as the Basque Pikorra cheese we had. A few were as forgettable as Velvetta. One I tossed into the pool (yes, I will name names). Another, a bestseller from a great series, put me, and my dog, to sleep. Most entertained me. And almost all of them taught me something about this maddening thing we call writing.

Here’s a sampling and what I learned from each. Apologies for the long post today, and I forgive you if you skim read.

The Financial Lives of the Poets. By Jess Walter. Matthew Prior quits his newspaper job to gamble everything on a quixotic notion: a web site devoted to financial journalism in the form of blank verse. Before long, he’s in debt, six days away from losing his home — and spying on his wife’s online flirtation. Then, one night on a desperate two a.m. run to 7-Eleven, he falls in with some local stoners. Havoc follows.

I loved this book. It’s gasp-out-loud funny. Surprising at every turn. Darkly satirical yet achingly tender. You ever get a book you start to read more slowly because you don’t want it to end? This was it for me. I’ve read only one other Walter book, Beautiful Ruins, his paean to crazy love starring a weird Italian trying to build a golf course on a Ligurian cliff, Burton and Taylor trysting during Cleopatra, and a doomed starlet. Richard Russo called it “an absolute masterpiece.” Walter has written only 10 novels, snapped up countless awards, and won the Edgar for his crime novel Citizen Vince. (I’m off to get it today).

THE LESSON. Trust in your ability to be original. Don’t be a pale copy of someone else. Take chances. The two Walter books I read are blazingly different yet both quirky and deeply affecting. As Walter told the New York Times: “I judged a contest once — 200-some books — and another judge said: ‘You’ll be surprised how many good books there are, and how few great ones.’ Indeed, there were many ‘well-written books’ but the great ones stood out for other qualities: audacity, originality, thematic weight. I think writers sometimes fall in love with this idea of “the gorgeous sentence” and it becomes their only definition of writing. But other elements are also part of writing; to me, an elegant narrative shape is every bit as beautiful as great prose.” Amen to that.

Me and Archie and Ian Rankin.

A House Of Lies. By Ian Rankin. Retired detective John Rebus gets pulled back in when a skeleton of a private eye is found in the woods. His old friend, Siobhan Clarke is assigned to the case.

I’ve enjoyed other Rebus novels and was eager to sink back into this evergreen series. But the pacing was glacial and too many characters are introduced too early — except for Rebus who shows up late for his own party. The Scots are said to be folks of few words. Not here. The cop banter is numbing. It’s the 22nd outing for Rebus, so maybe the old fellow was a bit tired. I don’t know. I gave up on page 72. Very put-downable.

THE LESSON: Keep the focus in the early pages on your protag. Establish a compelling fissure in the norm immediately. Don’t crowd your stage with minor characters too soon. Make your dialogue advance the plot — less talk, more action. And never forget that you’re only as good as your last book.

A Man Called Ove. By Fredrik Backman

Ove, an ill-tempered, isolated retiree who spends his days enforcing block association rules and visiting his wife’s grave, has finally given up on life just as an unlikely friendship develops with his boisterous new neighbors.

I plucked this off the shelf not expecting much. The ho-hum opening line: Ove is fifty-nine. He drives a Saab. And the Ove character is just really nasty and off-putting. Plus it’s set in Sweden. But this quirky, funny, dark book unfolds with grace and perfect pacing, toggling between the present and Ove’s childhood. It’s heartbreaking and ultimately life-affirming. I’ve since found out it’s a word-of-mouth international bestseller. (where have I been?) And it will be released this Christmas as a movie starring — who else? — Tom Hanks (renamed as Otto from Pittsburgh). I love it when I stumble upon a book having no expectations and then am blown away. Oh, as for that opening line: The author says his editor all but demanded that he change it — you need something juicier, editor said. Backman fought for the Saab line.

The Lesson: Yes, an unlikeable character can carry a story. But you must, as Fredrik Backman does with Ove, give your hero a sturdy and believable arc, allowing the plot and other characters to affect his development. Other lessons: Pay attention to your other cast members. Each one in this book has an impact — some small some major — on Ove’s life. Each is rendered with love and vividness.

A final lesson: Don’t agree with everything an editor tells you to do. Opening lines, at their best, telegraph to your readers the thematic heart of your story. The opening line about the Saab is a splendid example of what we here call “the telling detail.” The Saab comes to symbolize Ove’s very soul. Backman talks about this in a wonderful essay he wrote called “Something About a Saab”: Quote: “It’s a pretty weird process, writing a book…a lot of compromises are made, sometimes between the writer and the publisher…but mostly between the writer and the writer. Ideas are edited, dialogues are shortened, characters are fired. Editors like to call this process killing your darlings. If there is one thing in this whole novel process that wild horses and armed men could have never convinced me to get rid of it was that second sentence: He drives a Saab. I could have written twenty pages and never gotten as much said about Ove as with those four words…Above all you know exactly what men who drive Saabs would have said about us. Because cars are not nous. They’re adjectives.”

Which is why, when I finally divorced my first husband, I got rid of my Honda Accord and bought a TR6 convertible.

Sea of Tranquility and Last Night In Montreal. By Emily St. John Mandel.

You might know from my previous posts that I’m a big fan of this writer. Her Station Eleven and Glass Hotel are two of the best books I’ve read in the past five years. I splurged on a hardcover of her latest Sea of Tranquility. It involves time travel, love, and plague that takes the reader from Vancouver Island in 1912 to a dark colony on the moon five hundred years later, unfurling a story of humanity across centuries and space. Loved this book! So I grabbed a used copy of her first book Last Night in Montreal at the Abbey Bookshop, ready to be entranced again. Oh brother, what a hot mess. The main character Lilia was abducted in the night by her father. As an adult, Lilia wanders from city to city, lover to lover, eluding a PI who’s obsessed with finding her. There’s a second character Eli, also obsessed with her, trailing her like a sick puppy. Lots of dark hints about a tortured childhood, a bad mom, and such. But mainly, it’s Lilia and Eli whining about their useless lives, as the detective — totally without motivation –lets his relationship with his own daughter wither and die.

The Lessons: Sea of Tranquility taught me that you can indeed whiplash readers through time but only when you’ve got the firmest grasp of your craft. Mandel never gets you confused. Plus she’s a master at world-building. I totally believed her scenes set on the moon colonies. Last Night in Montreal taught me that SOMETHING HAS TO HAPPEN. (Boy, you haven’t heard that here before, right?) And that whining isn’t deep. It’s just boring. Oh, and that big secret about her bad childhood? A big meh at the end. Lesson: Don’t set up some juicy plot tease and then not follow through. (Montreal is the book that landed in the pool.) And a final lesson for you all just starting out: Yes, your first book might be flawed but put it behind you and keep moving forward. There’s maybe a Station Eleven — it won the PEN and National Book Award and was an HBO series — waiting to claw its way out of you.

La Sentence By John Grisham

By my final three days, I had exhausted the rental house’s English novels. There was just John Grisham left. Now, I’m not a Grisham fan. I concede he’s a good storyteller but his writing sounds clunky to my ear. Also, this book was in French. It was called La Sentence, a translation of Grisham’s 2018 family saga cum mystery cum war novel The Reckoning.

Thanks to years of adult ed and Babbel, I have a passable reading knowledge of French. So, dictionary in hand, I cracked open La Sentence, ready for a long slog. The story hooked me immediately. It is 1946 and wounded war hero Pete Banning has returned to his family cotton business in small town Mississippi. Page one: On a cold morning, Banning wakes before dawn and decides today is the day he will kill someone. He knows it will change the lives of everyone he cares for, but “the killing became as inevitable as the sunrise.”

I’ve tried to read French novels before — mainly Georges Simenon’s Maigret series — but the native language’s nuances frustrated me. But this was easier reading, maybe because it is so plot-driven. Also, I began to wonder if Grisham’s translator had added something, making the description and emotion more musical. When I got home, I got a used copy of The Reckoning in English and compared the two.

Take this line in the French version, from a scene where Banning is heading toward town, surveying the cotton fields and workers as he drives.

Les fleurs de coton, emportées par le vent, saupoudraient la route derrière les charrettes.

Here is how I translated it (and checked it via Google):

The cotton flowers, carried away by the wind, powdered the road behind the carts.

But here is how it appeared in The Reckoning (original English) as Grisham actually wrote it:

Cotton blown from the trailers littered the shoulders of the highway.

Note the difference in word choice: “flowers” instead of cotton balls. “carried away by the wind” instead of “blown” and “littered.” And there’s the use of that verb saupoudre, which in French is used most often to describe powdering a cake with white sugar.

THE LESSON: Word choices matter. Given his massive success (and The Reckoning was well reviewed), maybe Grisham needn’t worry about finding the great word or well-turned phrase. But given this book’s sad opening and almost elegiac tone, I wish he had tried harder to give Pete Banning a better soundtrack. I’m going to finish the book, but sticking with the French version. I like a little powdered sugar with my plots.

So, what have you all been reading lately? And what did you learn from your reading that helped you as a writer?