Put on your waders because we’re going deep into the fiction-writing bulrushes today. I want to talk about one of my favorite micro-topics — transitions. Actually, maybe it’s quicksand we’re wading into, because if your book doesn’t have good transitions, it can sink faster than Janet Leigh’s ’57 Ford in Psycho.

We talk a lot here at TKZ about how important pacing is, and transitions go along way to creating that seamless narrative flow you need as your story shifts in time, location, or point-of view. But here’s the thing: Transitions look easy but they can be tricky to get right.

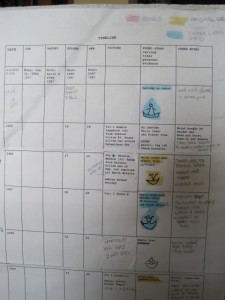

I think I dwell on transitions so much because I work with a co-author. Kelly and I write our books by talking out the plot then writing alternating chapters. So we don’t have the normal one-brain flow of a unified writing procedure. We always know the purpose of each chapter but often we write with no clear idea of what the links between the chapters will be. Sometimes we just leave red-ink pleas like this for each other —INSERT BETTER ENDING HERE — then we deal with links in rewrites.

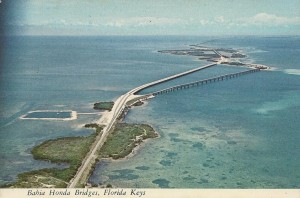

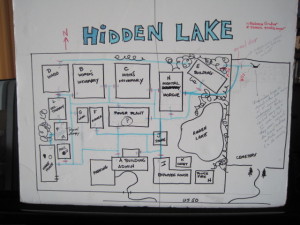

I used to think this was nuts but then I read an interview with Katherine Anne Porter wherein she described her writing process as “creating scene islands” and “building bridges” between them. This gave me great comfort, knowing I could approach writing like a good engineer. Getting my chapters to flow became akin to making the long journey to Key West.

It also made me think that maybe the island-bridge analogy is useful for those of you who work alone. Because the scene (and by extension chapter) is the terra firma of your plot structure and once you have that solid you can always go back and figure out the best ways to move between those plot clots. A consistent problem I see with critique manuscripts is that the writer often doesn’t know where to end a chapter for maximum impact. And that leads to not knowing where to pick up the next one. It is helpful, I think, for writers who struggle with this to concentrate on figuring out what the MAIN PURPOSE of each scene/chapter is, write that plot clot, and then fine tune the bridges later. I’ve often found that if I just keep telling the story — even if that means sticking in some really pedestrian transition just to keep moving forward — that when I go back later in rewrites the perfect transition jumps out at me.

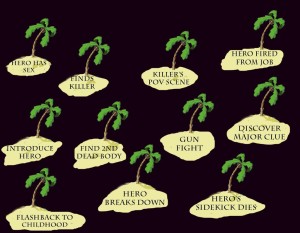

So what exactly is a transition? Well, there are all kinds. Most are straightforward and literal; some are complex and sophisticated. But all good transitions do one thing: They strengthen the internal logic of your story by moving readers from idea to idea, scene to scene, and chapter to chapter with grace and ease. I’m going to move the lens out here and just talk about chapter transitions for now. Here’s some of the ones I’ve identified. Maybe you guys have some others?

Time Transition: This is when you want to move forward (or occasionally backward) in time with your story. These are pretty workmanlike but very useful in that they simply bridge time from your previous scene. (Unless noted, all examples here are from our latest book HEART OF ICE).

Chapter 4

It was nearly three by the time Louis met Flowers at the docks.

Chapter 7

Just over an hour later, Dagliesh had left the headland and was driving west along A1151. (P.D. James)

A word about time stamps. These are the tags you see at chapter beginnings ie “Sunday” or “November 1967” or even just “Later that day.” I have a slight bias against time stamps because too often they are a cop-out by a writer who can’t figure out how to gracefully weave time changes in the narrative. But sometimes you really need them, especially thriller writers who work on big canvases. If your story is happening at two different times, time stamps help the reader move between the threads, i.e. “New Orleans, 1855” or “Kabul 1999.” In his thriller

The Phoenix Apostles, our own Joe Moore (with Lynn Sholes) pin-balls between Mexico, the Bahamas, Paris in present time and Reno, Washington D.C. and even 1899 Chicago. Without his time/location stamps we’d be lost!

Time/location tags can be pretty elaborate. In her complex novel about 9/11, Absent Friends, S.J. Rozan weaves multiple narratives together by using tags like so:

PHIL’S STORY

Chapter Six

___

The Invisible Man

Steps Between You and the Mirror

This is grad school stuff; Rozan knows what she’s doing. Another good use of time stamps is found in Gone Girl. Gillian Flynn must find a way to bring the missing wife Amy to life so Flynn alternates the husband Nick’s present-day narrative with his wife’s diary entries, all clearly marked with time/name stamps.

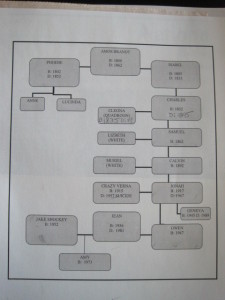

Point of View Transition: When you move between characters, you could just pick up with the new character’s voice. But the flow can be enhanced if you find a way to subtly link them. Here is Louis talking to a police chief about the abandoned hunting lodge where they just found old bones at the end of Chapter 6:

“Nobody comes here. It’s just a broken down old dump,” the chief said.

Louis shook his head. “No, it’s important. It’s his Room 101.”

“What?”

“It’s from Orwell…1984.”

“Never read it.”

Flowers moved away and Louis looked back at the lodge. He could still recall the exact quote from the book – maybe because it reminded him of things in his foster homes he wanted to forget.

The thing in Room 101 is the worst thing in the world.

Chapter 7

There were thousands of them. Small, black jelly-bean creatures crawling around the plastic bin, piggybacking one another to get to that one last shred of meat on the bone.

The beetle larvae were hungry today.

This skull would be ready by nightfall.

Danny Dancer made sure the lid was secure on the bin and left the room.

By using the Orwell “room” quote we tried to lead the reader to the horror of what they were about to see in Danny Dancer’s room. Change of POV but bridged with purpose.

Continued Narrative Transition: Here, the story simply continues from what came in previous chapter. The main artistic choice you makeis how much time elapses between scenes. It can be minutes, days or years. Here’s John Sandford ending Chapter 14:

“He tried to hang Spivak, for Christ’s sake,” Lucas said, exasperated.

“That was just part of the job,” Harmon said. “You can understand that.”

Chapter 15

Lucas couldn’t. He got off the phone, breathing hard for a few minutes, backed off the gas.

Sometimes, the continued narrative transition can be deep in a character’s pysche. Here’s a nice transition from Jeff Lindsay’s Dearly Devoted Dexter at the end of chapter 10:

The only reason I ever thought about being human was to be more like him.

Chapter 11

And so I was patient. Not an easy thing, but it was the Harry thing.

The thing with this transition is that you the writer have to make calculated decisions on where to pick up the action and what you can leave out in the lapse. Say you end a chapter with a cop getting a call at home to come to a crime scene. Where do you pick up the thread? Do you show him strapping on the gun, getting in the car, walking up to the yellow tape? Or is it more effective to begin the next chapter with “As Nick took his first look at the woman’s body, he realized with a start he had seen her face before.” Here’s exactly such a passage from Val McDermid’s splendid A Place of Execution:

End of Chapter 11

The door to the caravan burst open and Grundy stood in the framed doorway, his face the bloodless grey of the Scardale crags. “They’ve found a body,” he said.

Chapter 12

Peter Crowther’s body was huddled in the lee of a dry-stone wall three miles due south of Scardale as the crow flies. It was curled in on itself in a fetal crouch, knees tucked up to the chin. The overnight frost that had turned the roads treacherous had given it a sugar coating of hoar.

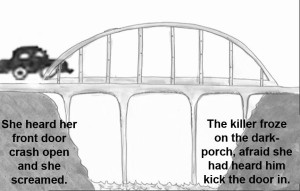

Action/Reaction Transition: When you have a juicy action scene it can be very effective to break at just after the action peak and open next chapter with a character-focused reaction: Here is the end of our chapter 17, an ambush where Chief Flowers gets shot.

“Clear! We’re clear! Get the ambulance in here now!”

Louis’s heart was finally slowing but he still had to blink to clear his head. Joe was kneeling by Flowers, and from somewhere down the dirt road sirens wailed.

He heard a whimper and looked down at Danny Dancer. The bastard was crying. Curled up like a baby and crying.

Chapter 18

How could he have been so stupid? He knew that anyone who showed an abnormal interest in a crime scene was someone who needed to be treated with suspicion.

Yet he had allowed Flowers, who was blind to the idea that anyone on his island could be a cold-blooded murderer, walk into a crazy man’s line of fire.

At beginning of Chapter 18, an hour has elapsed and Louis is waiting in the hospital as Flowers lays dying. We chose this transition because the “quiet” moment of Chapter 18 provides relief for the reader after the tension of the ambush, much like letting you catch your breath after the steep drop of a roller coaster. It’s all about pacing.

Descriptive Transition: This is another way to alter your pacing. Say you had a explaining-the-case chapter with heavy dialogue between investigators. It’s often effective then to go from staccato to legato and open the next chapter with a descriptive passage. And yes, you can use weather — in moderation! It is also a good way of telling your readers where we are. I’m of the mind that description transitions should only be used early in your story because they can slow things down too much once your plot-engine gets really chugging. UNLESS, like Joe Moore, you are globe-hopping, and then a well-honed location description can be a sturdy bridge. Here’s Elaine Viets in Murder With Reservations, opening chapter 3 with a description that also slips in some protag’s backstory:

Helen grew up in St. Louis, where houses were redbrick boxes with forest green shutters. To her, the Coronado Tropic Apartments were wrapped in romance. The Art Deco building was painted a wildly impractical white and trimmed an exotic turquoise. The Corondado had sensuous curves. Palm trees whispered to purple waterfalls of bougainvillea.

Echo Transition: This is a nifty little device wherein you end a chapter stressing a certain word then use that word again as your bridge to the next. It’s like a grace note in music. Lee Child is a master of this and here’s the end of his chapter 6:

“You have to do something.”

“I will do something. Believe it,” Reacher said. “You don’t throw my friends out of helicopters and live to tell the tale.”

Neagley said, “No, I want you to do something else.”

“Like what?”

“I want you to put the old unit back together.”

Chapter 7

The old unit. It had been a typical Army intervention. About three years after the need for it had become blindingly obvious to everyone else, the Pentagon had started to think about it.

The Parallel Transition: This can be really cool but if you whiff on it, it just looks like you’re showing off. This is used when you are shifting POV’s. It is conscious repetition of an idea, image or symbol between two chapters. Like the Echo Transition, it creates an almost musical connection in the reader’s mind, like a good hook in pop music. And it doesn’t always come at the end/beginning of chapters. Here’s the first paragraph of Chapter 1 of our thriller A Killing Song. We are in the killer’s POV in Paris as he watches his next victim:

He couldn’t take his eyes off her. The last rays of the setting sun slanted through the stained glass window over her head, bathing her in a rainbow. He knew it was just a trick of light, that the ancient glass makers added copper oxide to make the green, cobalt to make the blue, and real gold to make the red. He knew all of this. But still, she was beautiful.

Here is the opening of chapter 2, from the protagonist’s POV as he watches his sister dancing in a Miami Beach nightclub:

I couldn’t take my eyes off of her. Maybe it was because I hadn’t seen her in two years and in that time she had passed through the looking glass that separates girls from women. Whatever it was, Mandy was beautiful and I couldn’t stop staring.

This was a calculated thing for us because the book’s theme is partly about the two men whose lives spiral out of control and the fine line between violence that is driven inward and outward. (And yes, we mixed first and third POV but that’s a different post for another day.)

Two last thoughts about building bridges. First, transitions are just a tool, a part of your writer’s technique, and as such you can learn to use them with flair and confidence. Study writers you admire. Go grab a book and open to the blank spots between chapters. Then analyze how the writer has moved through time and space, how he has bridged the gaps between his chapters. You’ll find that most of the time, the best writers adhere to the golden rule: KISS. They keep it simple, stupid. Which leads me to my last thought:

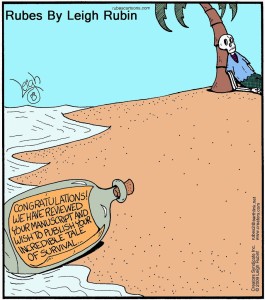

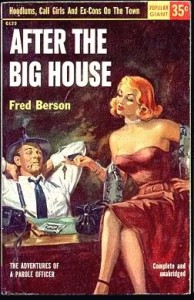

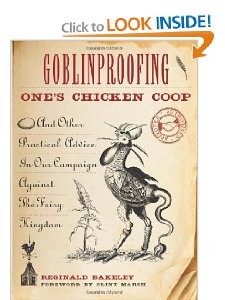

Don’t over-think this. Resist the urge to build this:

When all you need is this:

Your first job as storyteller is to just keep the reader moving between your islands. You don’t want them to stop and admire turrets, filigree and gargoyles. More often than not, a sturdy little span is the best way across.