By P.J. Parrish

When I write, I don’t read. Because I know, from experience, what happens when I do. I steal.

Now, don’t get me wrong. All writers steal. At least, the smart ones do. Because this is partly how you learn to write a novel, by reading other novels, figuring out how the person structured the story, analyzing how the characters were layered, how the motivations were laid out, how the words were put together to elicit an emotional response. We learn by digesting the craftsmanship of others.

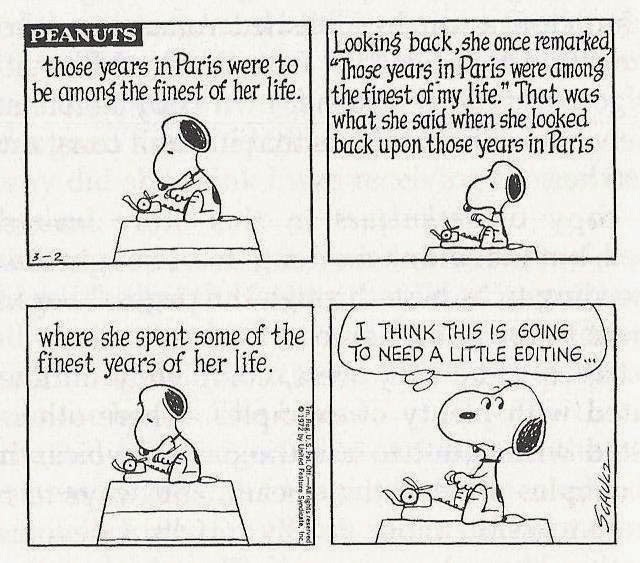

Here’s the thing though: You have to steal in the right frame of mind. And for me at least, that is NOT when I am working on my own book. If I see a way of structuring a scene or chapter that is clever, I will try to replicate it in my own book. If I read a passage that sings, I will try to mimic it even if it’s not my style. When I am writing, I am in this weird fugue state and my brain is very porous and open. The temptation to take things that really don’t belong to me is too great.

But something changes once I am done writing my own book. I binge read for pleasure. Freed from my own insecurities and writer ego, I hear other writers more clearly. And when that happens, I learn more about writing in general and the lessons sort of sit in my brain, baking and bubbling, until I need them.

So, yes, I steal from other writers. Here are some of the things I have taken and the people I took them from:

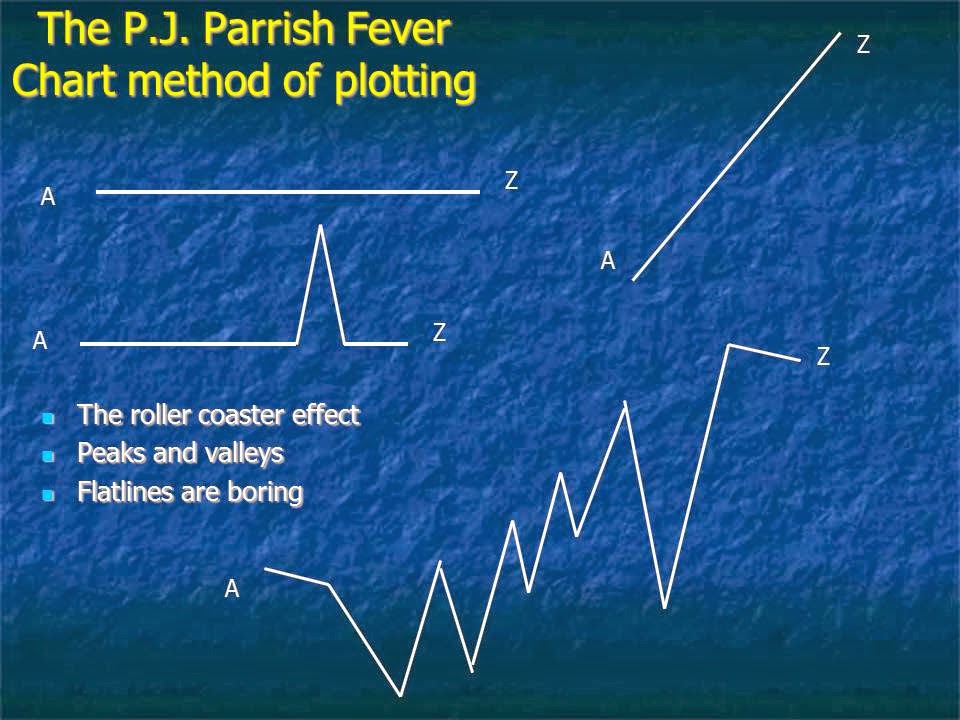

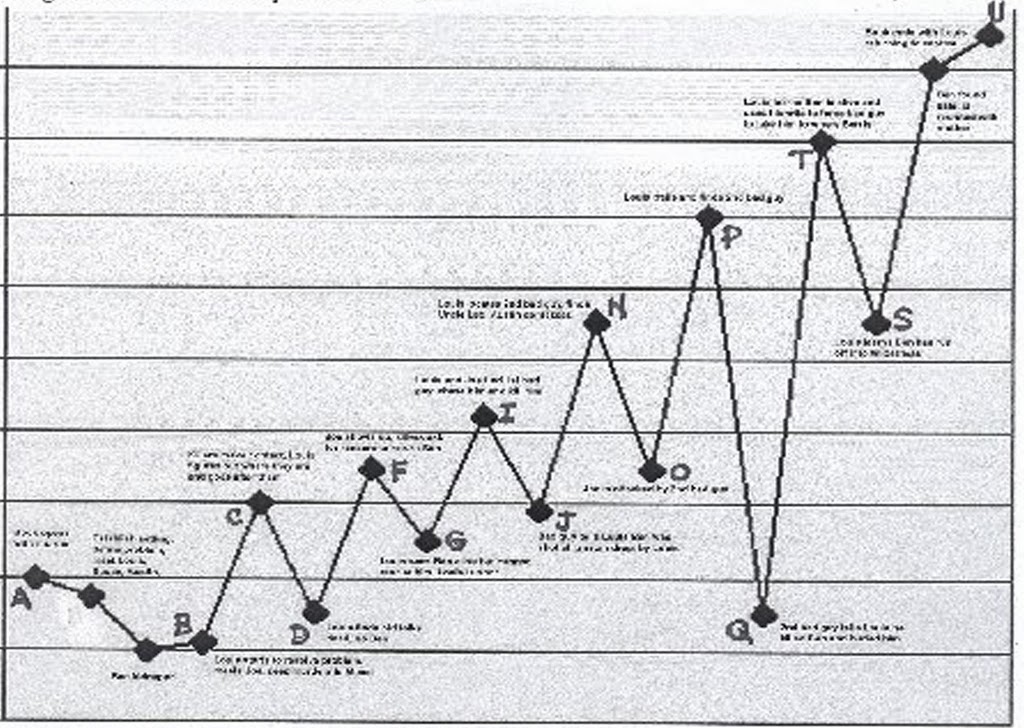

Every sentence must do one of two things: reveal character or advance the action. I stole this from Kurt Vonnegut. About ten years ago, I was struggling mightily to write my first short story. I went back and read Cheever, Hemingway, Saki and O Henry. I discovered John D. MacDonald’s The Good Old Stuff. But it wasn’t until I got to Vonnegut’s Bagombo Snuff Box that I hit pay dirt. In the preface, Vonnegut laid out his eight rules for writing. (Click here to read them all.) His idea that every sentence must reveal character or advance plot was a light bulb moment for me. It now informs everything I write. And when I teach, I try to impress on writers that every scene, every chapter, must work hard in service to the twin poles of character and plot.

Kill Your Darlings. Nope, I didn’t get this one from Faulkner. I stole this from E.B. White. And by “darlings” I mean good characters. Charlotte’s Web is my favorite book, maybe the one that most influenced me as a writer. It has many great lessons but the most enduring is that a writer can – must – be brave enough to kill a good character. I’ve written about this before, so click here if you want to read more.

Fall in love with the sound of language. Stole this one from Truman Capote after reading Music for Chameleons. This is a miscellany of stories and essays published in 1980 after a 14-year drought following Capote’s brilliant In Cold Blood. It contains passages of exquisite beauty and it taught me, when I was just starting to write, to pay attention to what words sounded like. Like those chameleons in the lead story, I was mesmerized by the music, and have spent all the years since trying to make my own. (In his preface, Capote writes: “When God hands you a gift, he also hands you a whip for self-flagellation.” Ha!)

Don’t be afraid! This one I got from Mike Connelly’s The Poet. For most of our Louis Kincaid series, we have stayed mainly with a third-person intimate POV because we think filtering the story through our hero’s consciousness enhances the reader’s bond with him. But when we started our first stand alone thriller, The Killing Song, we realized our protag and villain were equally important. We needed something special to drive home their dichotomy of good and evil, so we decided to copy Connelly’s The Poet and mix first and third POVs. Our first chapter was written in first-person from the killer’s POV and the second chapter switched to third-person from the hero’s POV. But it wasn’t working. And we couldn’t figure out why. I ran into Mike at Bouchercon and told him I stole his idea. He smiled, shook his head and said, “But give the first-person to your hero. It’s his story.” We took his advice and the story took off. But I wouldn’t have had the guts to try without reading The Poet.

There have been other lessons learned from my life of crime. From Stephen King, who has tried everything from horror to westerns, from eBooks to novellas, I learned not to let expectations box me into one genre or style. This has given me the courage to use an unreliable narrator in my WIP. As E.B. White said, “Sometimes a writer, like an acrobat, must try a trick that is too much for him.”

From Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, I stole the idea that a protagonist can be deeply flawed. From Jane Austen’s Emma I learned to pay attention to secondary characters because they might hold the key to the story (In the end, George Knightley won Emma’s heart). From Pete Dexter’s Paris Trout, I got the revelation that all good crime stories are not about the crime but rather its rippling effect on the people and the town. And last but not least, From Anne Lamott, I learned that my quest for perfectionism is death. She wrote in Bird by Bird: “The only way I can get anything written at all is to write really, really shitty first drafts.” Which might be the best advice for writers I have ever heard.

Who do you steal from? And what treasure did you get?