So there I was, standing in the corner at the Christmas party Friday, nursing my apple-tini and watching the crowd, when my friend Trent sidled up.

Trent’s dream job is to be Clinton Kelly on “What Not to Wear” so at the party he was mentally undressing the women and then re-dressing them. He is also a disciple of the Alice Roosevelt Longworth axiom “If you can’t say anything nice about somebody, come sit by me.” (Teddy’s daughter once described Calvin Coolidge as “looking like he was weaned on a pickle.”) And this being a Christmas party, you can imagine that Trent had a lot of material.

He says that there’s something about dressing up that just confounds some women down here in South Florida, particularly during the holidays. I have to agree with him. Women start out okay with maybe a little black dress. But then too many pile on every button and bow, every piece of bling they own. Trent calls it “the Full Boca.”

Okay, I’m picking on the women here, but men have it easy when it comes to formal wear; you have to try really hard to mess up a tux. But women? Some of them just don’t know when to leave well enough alone.

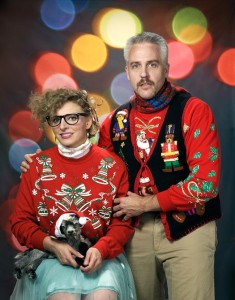

And standing there at the party with Trent, I realized a lot of writers have this same problem. Me, included. So let’s talk about description and how to keep your book from turning into an ugly Christmas sweater.

Description is maybe the most potent tool in our narrative toolbox. It sets a mood, signposts a sense of place, and renders characters into flesh and blood. Description has the crucial function of letting the reader

sense — see, hear, smell, feel and taste — what it going on in your story. If your description is truly compelling, it can make a reader believe in things that are otherwise incredible. Think of what Stephen King does with “Salem’s Lot.” By making his mythical Maine town come alive through description, we are willing to suspend disbelief when the vampires start showing up.

Speaking of King, here’s what he says in his book “On Writing”:

“Description begins with visualization of what it is you want the reader to experience. It ends with your translating what you see in your mind into words on the page. It is far from easy. We’ve all heard someone say, ‘Man, it was so great (or horrible/ strange /funny)…I just can’t describe it!’ If you want to be a successful writer, you must be able to describe it, and in a way that will cause your reader to prickle with recognition. If you can do this well, you will be paid for your labors. If you can’t, you’re going to collect a lot of rejection slips.”

“Prickle with recognition.” Isn’t that a great way to put it?

Why do so many of us struggle with description? I think it’s because many writers don’t know how much description to use. Some don’t use enough. But usually, they have way too much. Description is narrative and narrative disrupts action. So a little goes a long way.

Which brings us back to the little black dress. When description is working well, it is concise and evocative. It also concentrates on a few well-chosen specific details that imply a host of other unspecific details. When Holly Golightly got dressed to go visit Uncle Sally in prison, she didn’t junk up her Givenchy. Just sunglasses and that great hat.

So how do you find your happy medium? How do you know when you’ve gone too far or haven’t gone far enough? How do you resist gilding the lily? There are no easy answers but here are a few things to think about:

Don’t generalize: Try to avoid abstractions. Be concrete in your descriptions. Instead of saying someone played a board game, say it’s Monopoly. Instead of a “bad smell” use the specific “like sour milk.” But again, don’t reach too hard or you look silly.

Don’t forget to compare and contrast. The secret to originality is the ability to see relationships. If you’re describing something green, it’s your job to come up with something fresher than “grass.” Here’s one of my faves from Steinbeck: “The customers were folded over their coffee cups like ferns.” And come to think of it, Alice’s description of Calvin Coolidge as “looking like he was weaned on a pickle” is pretty good. But again, don’t strain for originality or you just sound pretentious.

Don’t lean on adjectives: Just lining up a string of modifiers is lazy writing. (ie tall, dark and handsome). Try to find one vibrant adjective rather than several weak ones. But again, don’t strain or reach for the Thesaurus. Sometimes a lawn is just a lawn…not a “verdant sward.”

Don’t use cliches: It’s easy to slip into tired, flabby words. If you want to say something is white, you can’t use “white as snow.” It’s not yours! Neither is “thin as a rail, sick at heart, hard as a rock” or even “overcome with grief.” Time has eroded all those. It’s your job to find new ways of making your reader experience your fictional world.

Yeah, it’s tough to dress your writing for success. But don’t despair. Description is one of the things that you can get better at. Believe me, I know. I used to lard my paragraphs with lovingly crafted images that dammit, were going to stay in there because I worked so hard on them. But then my sister told me one day that I was — ahem — dressing to impress. I made every writer’s biggest mistake: I fell in love with the sound of my own voice and was trying to be “writerly.”

Finding your style — be it writing or fashion — is a lifelong process. When I went to my prom, I looked like a cross between Scarlett O’Hara and a Kabuki dancer. Through practice, I look a little better these days. Likewise, in my writing, I have learned what to leave off, what to cut out. In fact, I have gone too far with my WIP so my critique group friends tell me I am now underwriting and they are advising me to add more description.

Here is Stephen King again:

“Description is a learned skill, one of the reasons why you cannot succeed unless you read a lot and write a lot. It is not a question of how-to, you see; it is also a question of how much to. Reading will help you answer how much, and only reams of writing will help you with the how. You can only learn by doing. “

I’ll leave you with one final fashion icon as metaphor. If you try hard, you can get better at this. If she could go from this:

To this:

So can you.