The other day I caught an interview with Tony-winning playwright Terrance McNally. His new play Mothers and Sons is now on Broadway and he and its star, Tyne Daly, were talking about it:

Daly: Terrance is great at punctuation.

McNally: Punctuation is very important.

Daly: If you follow what he does, it’s like a musical score.

McNally: That would be in my notes, that it’s a comma not a semi-colon. I want to hear a comma and you’re giving me a semi-colon.

To which I said: “Yes!”

Did you notice that I used an exclamation mark there? That is because when I heard McNally talk about punctuation, I got really, really excited. Because I am one of those old-fashioned writers who believe that all those little marks we pepper in our fiction:

. ; : ? ! ( ) , “”

all those little marks make a big difference. So forgive me if I go in the weeds today (yeah, I know, I do this often) but I want to talk about getting the little stuff right.

But first, I’m thinking we need a definition of “right.” Because even though all of us savvy folks here at TKZ know we need to be up on our grammar so our editors will accept our manuscripts and our readers won’t flame us with Amazon one-star reviews, we also know that when it comes to fiction, rules can be bent.

In fact, sometimes they need to be bent. Sometimes, you the writer are going for a particular mood or effect or style, and if you do that with confidence, then grammar police be damned!

Take a look at this opening line of a famous book:

Marley was dead: to begin with.

That’s the opening line of A Christmas Carol. I’m not sure what Dickens was trying to do with it, and technically it’s a misuse of the colon. It probably should be “Marley was dead, to begin with.” But that’s flat and prissy. That oddly placed colon is like slamming up against a brick wall in the fog. I think it works in a weird sort of way. (Hat tip to blogger Kathryn Schulz for this example).

Here’s another strange one that I’m sure you’ll recognize:

Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins. My sin, my soul. Lo-lee-ta: the tip of the tongue taking a trip of three steps down the palate to tap, at three, on the teeth. Lo. Lee. Ta.

Again, misplaced commas, an inflamed colon, fragments and a plethora of periods. But it is music, no?

One more and then we’ll move on:

Grogan’s is not the oldest pub in Galway. It’s the oldest unchanged pub in Galway.

While as the rest go

Uni-sex

Low-fat

Karaoke

Over-the-top

it remains true to the format fifty or more years ago. Beyond basic. Spit and sawdust floor, hard seat, no-frills stock. The taste for

Hooches

Mixers

Breathers

hasn’t yet been acknowledged.

I can just hear the grammar gurus grinding their teeth over that one. This is from Ken Bruen’s Edgar-nominated The Guards. This is classic Ken, a style that ignores convention to create its spare lilt. Like George Saunders and Joyce Carol Oates, Ken plays with sentence structure, indention, and makes up new uses for all the old punctuation symbols. Because when he hears his story in his head, he hears a singular rhythm that you or I would not if we tried to tell the same story set in that Irish pub.

But here’s the thing: (colon!) These writers all knew the rules before they broke them. Charles Ives was a church organist before he broke away to write The Unanswered Question.

Picasso painted this

Before he felt free enough to paint this

William Strunk, the éminence grise of grammar, says: “The best writers sometimes disregard the rules. Unless he is certain of doing well, [the writer] will probably do best to follow the rules.” Or, as I often tell folks in my workshops: Don’t start juggling machetes if all you can control is two tennis balls. So maybe we should take a moment — pause em dash — to look at some of those little marks and decide which ones we can play around with without slicing ourselves to bits.

The Period

Wars have been waged over the poor comma. Some people are very strict about them, sticking them in every little compound sentence crevice. Others feel less is more, that fiction’s narrative voice allows you the freedom to “feel” your way around a phrase without the pause a comma injects. If you publish traditionally, your editor will have style manual and will inflict many commas on you. Some are bad:

Woman, without her man, is nothing

But some are good:

Woman! Without her, man is nothing.

The Colon

This is a pretty clear-cut fellow. It introduces text that amplfies something previously said or it tells you a list is coming up. I don’t think colons have much place in fiction, except maybe for that second use. A colon finds a better home in non-fiction. I think a better, less stodgy substitute for the colon is:

The Em Dash

I adore the em dash because to my eye and ear, it feels more like people really talk and think. Our thoughts tend to move forward and there is something pure and lively about seeing this — instead of this : A colon bring your eye to a stop while a dash implies there is more movement ahead. Two examples:

“The gambit is when you sacrifice one of your pieces to throw an opponent off,” the chief said. “There are many different kinds: the Swiss gambit, the classic bishop sacrifice, the Evans gambit.’

“The gambit is when you sacrifice one of your pieces to throw an opponent off,” the chief said. “There are many different kinds —the Swiss gambit, the classic bishop sacrifice, the Evans gambit.”

I think the second is better because it is dialogue. You also can use the em dash to show an abrupt break in the dialogue, when one person is cutting off another:

“Define insubordination.”

Louis wet his lips. “I did something — ”

“I don’t care what you did. Define the word.”

Which leads us to the ellipses. It’s a cousin of the em dash in that you see it used in dialogue often. But there’s an important difference. Whereas a dash implies an abrupt break in the dialogue, the ellipses implies a trailing off. It can also imply a slowing of thoughts.

“Why didn’t you quit?” Jesse asked quietly.

Louis shook his head. “Can’t…”

“Why?”

“He’s still out there.”

The Exclamation Mark

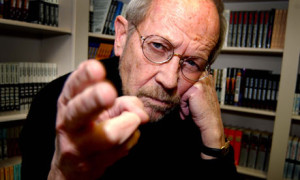

This thing can be like a rabid ferret…hard to control. Yes, you need a rare one to convey extreme emotion. But like a dash or italics, it can lose its effectiveness if you overuse it. As Elmore Leonard said: “You are allowed no more than two or three per 100,000 words of prose. If you have the knack of playing with exclaimers the way Tom Wolfe does, you can throw them in by the handful.”

The Semi-Colon

I saved this one for last because I hate the damn things. Semi-colons are like some professor-types. They’ve got an inflated sense of importance from living in the academic world. Or maybe they’re like literary novelists who like to go slumming in crime fiction. I think I’ve used maybe two semi-colons in sixteen books and both times I had to take a shower right after. I am not alone in my attitude. Let’s go back to what the playwright Terrance McNally said for a moment: “I want to hear a comma and you’re giving me a semi-colon.”

Our own James Bell called semi-colons the eggplant of punctuation. (Click here to read it). Why are semi-colons bad? Because the beautiful business of fiction is replicating real life on the page and in real life people don’t think or talk in semi-colons. Unless they’re using emoticons. And c’mon, don’t you want to punch out those people anyway?

Postscript: After I finished this, I was proofing one of my back list titles. It is filled with em dashes! The Em seems to be my default punctuation. That got to wondering why I hate the semi-colon so much and what this says about me as a person. So…

What Your Favorite Punctuation Says About You

Period: You are emphatic, decisive, fearless. In the life raft, everyone looks to you to figure a way out. You bowl overhand.

The exclamation mark: You’re dramatic and get a lot of invitations to parties. You wear purple. You’re probably the person people glare at for talking on your cell phone too loud at the bagel store.

The Em Dash: You are creative and optimistic. Life is a cabaret, old chum. You keep fresh kale in your fridge, wait for a Kraftwerk comeback and you root for the Knicks.

Question mark: You are deeply spiritual and people in meetings always wait to hear what you think. You have read and understood everything George Saunders has written. Your favorite color is tweed.

Colon: You’re organized and make to-do lists. People always ask you to arrange the Christmas office party but no one grabs you under the mistletoe. You do the Times crossword in ink.

Semi-colon: You are cautious and methodical but you change your mind easily. You have trouble ordering at a restaurant and often resort to eating off other people’s plates because you think you made a mistake in getting the sea bass. You think Rand Paul makes a lot of sense.