Our wonderful family here at TKZ runs the gamut in terms of how we are published. Some of us walk the self-published “indie” path, others the traditional. I get the impression a few are “hybrid,” journeying on both paths.

I showcased evergreen self-publishing words of wisdom last month, and wanted to do the same with traditional publishing today. While I am an indie, I have many author friends who are “tradpubbed.” For almost all of them working with an agent remains a vital part of their careers. For new writers who want to be picked up by a publisher, especially one the Big Five, an agent seems more essential than ever.

So, with that in mind, I found a post on agents by John Gilstrap from 2012, another from 2013 by James Scott Bell, and a 2016 post by Kathryn Lilley on avoiding pitfalls when querying agents. As always, the full posts are date-linked at the end of their respective excerpts.

I also want to highlight that JSB does an annual post on publishing, which is well worth reading.

What role does your agent play after the publishing contract is signed?

Understand that a lot of negotiation goes into what a publishing contract looks like. What rights will be sold? More importantly, what rights will be retained by the author? Is this a one-book contract, or a multi-book contract? What will the pay-out schedule be? If it’s a multi-book contract, will they be individually accounted or jointly accounted? (Joint accounting means that Book #1 would have to earn back its advances before you could start earning advances on Book #2. It’s by far the least preferable method, but first-timers often don’t have a lot of heft there.)

The agent is the go-between for all uncomfortable transactions. For example, in fifteen years, I have never discussed money issues with an editor, and no editor has had to tell me to my face that I wasn’t worth the money I was asking for. The agent keeps the creative relationship pure. Beyond that, if everything goes well, the agent doesn’t have a lot to do after the contract is negotiated.

But things rarely go well. What happens if your editor quits or gets fired? What happens if you really hate the cover, or if the editor is getting carried away with his editorial pen? On a more positive note, the agent will continue to pursue foreign publishing contracts, movie deals, etc.

What kind of deadlines are there? How firm are those deadlines?

Deadlines are part of the negotiation process. You’ll have to agree to respond to your editorial letter by a certain date with a corrected manuscript, and then you’ll have copyedits and page proofs, all while making your commitment to deliver the next book in the contract if it’s a multi-book deal. I consider deadlines to be inviolable. I’ve had to push the delivery date by a couple of weeks once, but I hated doing it because it inconveniences so many people, and it makes me look unprofessional. Here is another instance where a track record of performance keeps people from losing faith in the author. For first-timers, blowing a deadline can kill a career. Remember, by blowing the deadline, you technically violate the contract, which the publisher would have the authority to void.

Writers need to understand that publishing calendars are set 12 to 18 months ahead. Working backwards from those dates are the in-house deadlines for the production side of things (cover design, copyedits, publicity, ARCs, reviews, and a thousand other details). If a deadline is blown by as little as a month, publishers may pull the author’s book from the calendar and replace it with another, thus potentially adding months to the publication date.

John Gilstrap—March 16, 2012

Seriously, those agents I know are good ones: caring deeply about the success of their clients, hurting when they can’t place a project, or when a client is dropped by a publisher. But they know this is the duty they signed up for. They are professional about it.

That’s a key word, professional. In any business relationship, no matter how warm, there are duties. So it’s proper to ask what each party owes the other.

What do writers owe their agents? I think they owe them productivity, optimism, partnership and patience. There will be times, of course, when concerns must be expressed and details hashed out. Time for phone calls and complaints. But these should be rare in comparison to the positives.

A writer needs to listen. Part of a good agent’s job (we’ll get to bad agents in a moment) is to guide a career, and the writer (who ultimately makes the decision about direction) ought to consider and attend to an agent’s wisdom.

And just plain not be a “pill” (slang, 1920s, “a tiresomely disagreeable person.”)

I said we’d get to bad agents, and here’s all I have to say: it is better by a degree of a thousand for a writer to have no agent than to have a bad agent. A bad agent is one who will make you pay fees up front before reading or submitting something; who will slough you off to an editorial service which kicks back a finder’s fee to the agent; who provides no feedback on projects or proposals; and who throws up anything against several walls to see if it sticks. How does one find the good and avoid the bad? The SFWA has a post that’s very helpful in this regard.

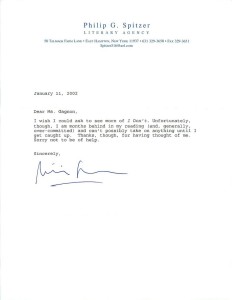

Now, what does an agent owe a client? Honesty, encouragement, feedback. But I think there is one thing above all, and that is what prompted this post today. Over the years I’ve heard from writer friends who are frustrated and sometimes “dying on the inside” because of lack of this one thing:

Communication.

When I was an eager young lawyer I took a course on good business practices from the California Bar. One item that stood out was a survey of clients on what they most wanted from their attorneys. At the very top of the list, by a wide margin, was communication. Whether it was good news or bad, they wanted to know their lawyer was thinking about their case or legal matter.

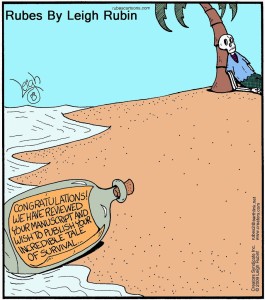

Writers are the same way. Even more so, because the insecurity of the business is an ever-present shadow across their keyboards. So if a writer sends in a proposal or list of ideas to his agent, and the agent doesn’t respond within a few weeks . . . and writer sends follow-up email or phone call, and still doesn’t hear from agent . . .this is not a good thing. In fact, for a writer, it is close to being the worst thing.

So I would say to agents what the California Bar says to young lawyers: just let the client know what’s going on from time to time. Especially if the client has sent something to you.

Now, I know from my agent friends that there are times when they can’t drop everything to communicate immediately. They have other clients, and things may be popping for one or more of them. It may be that the writer has submitted something that is going to take a lot of time to go over and assess. The agent may be off at a conference or maybe, gasp, needs some personal family time. All understandable.

But communication can be brief, even if it is just a short email acknowledging receipt.

James Scott Bell—May 5, 2013

Before there is an Agent and a Publishing Deal, there is every writer’s dreaded obstacle and Final Wall: the Query Letter. Here is a list of the top five reasons a query letter is rejected by an agent.

- Perilous Protocol

Manners and professionalism count. Your query letter will be met with an instant “No” if it doesn’t meet the minimum requirements of query letter protocol.

What is “protocol”?

It almost goes without saying, protocol requires you to pay close attention to an agent’s posted Submission Guidelines. Here are some links to excellent discussions about some other how-to basics of crafting a query letter.

The Complete Guide to Query Letters That Get Manuscript Requests, by agent Jane Friedman.

How to Write a Query Letter by agent Rachelle Gardner.

Query Shark (a site where where you can post your query letter for review, discussion, and critique)

- Misses and Misdirection

This point sounds obvious, but you must send your query letter to an agent who represents your manuscript’s genre. Do your homework. Research which agents are actively seeking new manuscripts in your chosen genre. (Genre-blending works are frequently problematic here–if you can’t pinpoint which genre your story belongs in, it makes it that much harder to attract an agent).

- “Good”, But Not Good Enough

The Truth: Agents aren’t looking for good writing. They’re looking for great writing. They’re looking for compelling, fresh writing that sizzles. “Good” (AKA amateur) writing simply won’t cut it in the current marketplace. So before you submit your query letter, make sure your writing meets that mark. You have to be brutally honest when judging the merits of your own writing. Compare your first chapter to some best sellers in your genre, and then ask yourself: am I there yet?

Kathryn Lilley—February 23, 2016

***

There you have it—posts on agents and querying them. I would love to hear your thoughts.

- Are you traditionally published, or aspiring to be traditionally published?

- What advice do you have on finding and working with agents?

- Have things changed since 2016 in terms of how advice on query letters?

- Do you have any other insights or advice on having a career in traditional publishing, or as hybrid author?