2024 Flathead Writers Conference

Photo credit: David Snyder

by Debbie Burke

The 34th Flathead River Writers Conference was October 5-6, 2024. The conference is always good, but this year was stellar with superb speakers and enthusiastic interaction among attendees.

As I drafted this post from my notes, it kept growing with more information that needed to be included. As a result, it ran way too long for a single post. So I’m dividing it into two. Today is Part 1 of the greatest hits from the event. Part 2 will follow in a couple of weeks.

~~~

Debra Magpie Earling (Native-American author of The Lost Journals of Sacajawea and Perma Red) gave the moving keynote which set the tone that continued through the entire weekend.

Debra opened with a description of “wonder”, which she defined as “surprise mingled with admiration.” She went on to tell a story of wonder about the last Christmas she spent with her dying mother. On a peaceful Montana night, she described their visit as like “being inside a snow globe.”

Her mother said, “When I die, I’ll send you a sign. A hummingbird.” Debra went along with her mom but had her doubts. After all, hummingbirds are common at her home during summer so how would she ever know which one was the sign?

Nevertheless, after her mother passed, the following spring Debra set up many feeders and waited.

It was a strange summer. Other bird species came and went. Crows sat on the feeders. But not a single hummingbird appeared.

On the evening of her mother’s birthday in July, Debra and her husband were sitting outside and Debra said, “Well, I guess she didn’t send the sign.”

At that moment, the only hummingbird of the year appeared. It flew to Debra’s forehead and hovered for a few minutes then left.

Debra and her husband asked each other, “Did you see that? Is that what I think it was?”

With that anecdote, she summed up the magical wonder of storytelling, the conference theme.

While talking about where inspiration comes from, Debra said, “The muse is a lot of dead people who want their stories told.”

That sentence sent chills through me. Recently I’ve considered writing historical fiction. Did Debra send me a sign that it’s time to explore the past?

~~~

Danica Winters

Million-selling Harlequin romantic suspense novelist Danica Winters told the audience, “This is not your grandmother’s bodice ripper.” Romance sales account for an astounding $1.4 billion each year.

Today’s variations are limitless: contemporary, historical, erotica, Young Adult, thriller/suspense, LGBTQ+, dark romance, paranormal, holiday, fantasy/romantasy. Even serious social issues like human trafficking find their way into romances.

Why are they so popular? Danica believes, “They are everyone’s escape. They bring joy and make people laugh. Romance is a promise. We writers are entertainers.”

Danica sells many more paperbacks than ebooks, unlike other genres where ebooks dominate. She added an interesting market detail: When Walmart changed its shelving to hold 6″ by 9″ books, that prompted publishers to shift book production to that same size because Walmart is such a huge market.

While most romance readers are women, Danica said about 20% are men, often in law enforcement and the military. Turns out even alpha males like escape, too.

~~~

Leslie Budewitz

Three-time Agatha winner Leslie Budewitz focused on crime fiction with an excellent summation of differences within the genre.

- Mystery is “What Happened?”

- Suspense is “What’s Happening?”

- Thriller is “What Might Happen?”

Leslie has her finger on the pulse of the cozy market and talked about shifts within the genre, including a new trend of millennial cozies that include some swearing and adult language.

For a cozy, the semiofficial acceptable body count is three. So far, Leslie has only had two murders in one book.

With 19 published books, Leslie must keep track of two amateur sleuth series and multiple standalone suspense novels. She developed an ingenious system to avoid repetition of plots and characters. For each book, she creates a spreadsheet with the following headings:

Victim Killer/Method Suspects Motive VGR

What is VGR? The Very Good Reason why the amateur sleuth gets involved in a crime.

~~~

Kathy Dunnehoff

Only a truly gifted writing teacher can make grammar entertaining. That describes longtime college instructor Kathy Dunnehoff, author of bestselling romantic comedies and screenplays.

Kathy offered nuts and bolts hacks to improve writing productivity.

- Measure your success by what you control, not by factors outside your control. Success is the number of words you produce.

- Use a writing calendar to track production either by word count or minutes…as long as that time is spent actually writing. Watching goat yoga or doomscrolling doesn’t count.

- When you don’t write, record your excuse in the calendar. Talk about making yourself accountable!

- Recognize procrastination in its many disguises: research, reorganizing your office, talking about writing rather that writing, etc.

- When revising, try the “Frankenstein Method” (from Jessica Brody’s Save the Cat Writes a Novel): Start a new document for the second draft, then copy and paste sections from the first draft.

- There is no extra credit for suffering!

~~~

On Saturday evening, our local indie shop, the BookShelf, hosted a reception for conference attendees and speakers. Gather a bunch of writers in a bookstore and we’re more excited than dogs at the dog park. Even though people mock-complained their brains were overloaded and they were exhausted, no one wanted to leave. All that creative energy kept us buoyed and eager for the following day.

Come back here in two weeks for Part 2 of the Greatest Hits from the Flathead River Writers Conference. Highlights include freelance article writing, side hustles to supplement income from book sales, anatomy of a publicity campaign, and 16 questions an agent asks when assessing a manuscript.

~~~

TKZers: Do any of the ideas mentioned resonate with you? What is your favorite productivity hack?

~~~

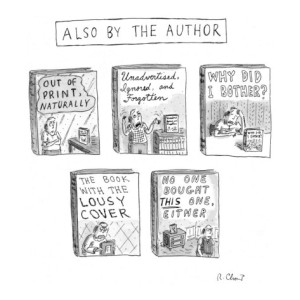

Conferences are also a good venue to sell books and I did!

Please check out my latest thriller Fruit of the Poisonous Tree at this link.