https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s0sbTLCLpgY

By PJ Parrish

As you know, I have trouble sleeping. Usually, it is because I can’t slow down the hamster wheel in my head. It is whirring around, filled with junk, to-do lists, misconjugated French verbs, woes real and imagined and regrets (I’ve had a few, too few to mention).

And then there are those story ideas floating around in my brain just as I’m trying to drift off. Those tantalizing fragments of fiction, those half-seen shadows of characters-to-be, those little loose pieces of plots just waiting to be sculpted into…

Books?

Here is the question I was pondering last night just before I finally drifted off: Is every idea worthy of a book? Does every story really need to be told? And then, in the cold light of morning, the answer came to me: NO, YOU FOOL!

You all know what I am talking about. Whether you are published yet or not, you undoubtedly have some of the following around your writing area:

1. A manila folder swollen with newspaper clippings, scribblings on cocktail napkins, pages torn from dentist office magazines, notebooks of dialogue overheard on the subway, stuff you’ve printed off obscure websites. At some point, you were convinced all these snippets had the makings of great books. (I call my own such folder BRAIN LINT.)

2. A folder icon in your laptop called PLOT IDEAS or some variation thereof. These are the will-o-wisps that came to you in the wee small hours of the morning, whispering “tell my story and I will make you a star!” So you, poor sot, jumped out of bed, fired up the Dell and tried to capture these tiny teases.

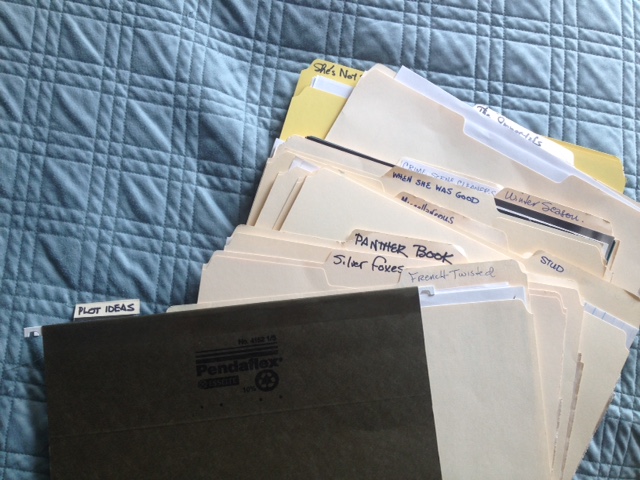

Here’s a picture of my PLOT file. Here are some of the WIP titles: Stud, Panther Book, Silver Foxes, Winter Season, The Immortals, Card Shark. Feel free to steal any of these.

Here’s a picture of my PLOT file. Here are some of the WIP titles: Stud, Panther Book, Silver Foxes, Winter Season, The Immortals, Card Shark. Feel free to steal any of these.

Or maybe you’re one of those bedeviled souls who keeps a notepad by the bed — just in case. (Mine is right under my New York Times Crossword Puzzle Book and paperback of John D. MacDonald’s Ballroom of the Skies.

3. Manuscripts moldering in your hard-drive. Ah yes…the stunted stories, the pinched-out plots, the atrophied attempts, the truncated tries. (Sorry, when alliterative urge strikes, you have to let it out or it shows up in your books). These are the books you had so much hope for and they let you down. These are the books you went thirty chapters with but couldn’t wrestle to the mat for the final pin. These are the books you grimly finished even as they finished you. Maybe you even sent these out to either agent or editor and they were rejected. At last count, I have six of these still breathing in my hard-drive. And at least four others finally died when my Sony laptop did, lost to mankind forever.

So what do you do with all these ideas? You expose them to sunlight and watch them burn to little cinders and then you move on. Because — hold onto your fedora, Freddy — not every idea is a good one. Not every idea makes for a publishable book. And sometimes, you just gotta let go.

Let me give you a metaphor. I think you women out there will get this more readily than the guys. You have a closet full of clothes. Most of the clothes you never wear. But they were really good ideas at one time. Like that hot pink Pucci shift you found at the consignment store but makes your boobs disappear. Like those Calvins you haven’t been able to shoehorn into since 1985. Like that yellow blouse you got at Off Fifth that makes you look like a jaundice patient but you keep it because it is Dolce & Gabanna and you paid $59.99 for it.

I read a good blog entry a while back about “Shelf Books.” I am kicking myself for not writing down who coined this great term; I’m thinking John Connolly? Someone please help me if you know. The idea is that you sometimes have to finish a book just so you can get it out of your system and move on. Doesn’t that make sense? Sort of like cleaning out your closet of clothes that make you frustrated and sad, so you can create space for good new stuff?

We all have Shelf Books. Some are meant to be only training exercises. They teach you valuable lessons that you must learn in order to be a professional writer. I will never forget listening to Michael Connelly talk at a Mystery Writers of America meeting when I was just starting out. He said that he completed three novels before he wrote his Edgar-winning debut The Black Echo, because he knew none of the first three were ready to go out into the world. Fast forward fifteen years to last month when I moderated a panel at SleuthFest with our guest of honor C.J. Box, who told the audience that he wrote four books before he finally hit it right with Open Season (which, like Connelly’s debut, also won the Edgar for Best First Novel.) And I clearly remember reading Tess Gerritsen on her blog where she confessed she wrote three books before she got her first break with Harlequin. She also said how dumbfounded she was that some writers expect to get published on their first attempt.

I think I understand that last thing. I had the hubris to think the same thing myself when I was starting out. But it took me a couple tangos with bad ideas before I found a story that worked. I have also seen some of my published friends lose valuable time not wanting to give up on an idea because they got so emotionally invested in it. And I have seen many unpublished writers lock their jaws onto one idea like a rabid Jack Russell and chew it to death. We all can become paralyzed, unable to give up on our unworkable stories, unable to open our imaginations to anything else. I think it is because we fear this one bone of an idea is the only one we will ever have. Don’t let anyone kid you — even veteran writers get into this mindset, frozen with fear that they have dried up, that they will never again have another good idea.

For unpublished writers, two things happen when they reach this point:

They self-publish — badly. Meaning without getting editing help or good feedback.

Or they get smart, take to heart whatever lessons that first manuscript taught them, put that book on the shelf, and move on to a new idea.

Here is my favorite quote about writing. I have it over my computer:

The way to have a good idea is to have many ideas.

— Jonas Salk

You have to know when to let go. And you have to trust that yes, you will have another idea. Maybe a good one. Maybe even a great one.

I think I will now go clean out my closet. There is a gold lame thrift store jacket in there I need to get rid of. Here it is. It’s yours if you want it. Check out my ad on LetGo. I will even throw in my un-used book title STUDS.