By PJ Parrish

So here I am, sitting in my Starbuck’s auxiliary office, and suddenly I woke up and smelled the coffee.

I had this epiphany about writing. It is just like making coffee. Some folks have a natural ability to make great coffee. They can start with the cheapest Maxwell House in the supermarket, add tap water, and it comes out tasting like Starbuck’s Rwanda Blue Bourbon made in a Bunn Tiger XL Super-Automatic Espresso Machine. Others can’t boil water for a tea bag without scorching the pot.

I am in this latter category. I’ve tried every kind of bean and brewer but my coffee always comes out tasting like dishwasher residue run through yesterday’s old paper filter.

For the life of me, I don’t know where I go wrong.

Now, my sister? Her coffee is always great. Even though she has a Mr. Coffee she found at a garage sale, has Northern Michigan well water, and uses Folger’s Classic Roast. When she comes to stay with me, she uses MY coffee stuff, my filtered water, my grinder, my Braun brewer and my Fresh Market cranberry-chocolate whole beans, and it still comes out better than mine every time. If you are like me and find that your coffee is not turning out the way you want it, then maybe it is time to invest in a new coffee machine. That is what my sister did and the results are way better than before and better than mine. The best way for me to make up my mind about what coffee machine I wanted next was to look at reviews. This way how I managed to make a quick decision, otherwise I would have been there forever. If I wasn’t recommended to look into a company like Identifyr, I probably would still be drinking my poor coffee from my old machine. For anyone in this situation, I would recommend that you treat yourself to a new coffee machine, to finally get the perfect cup of coffee and guess what goes fantastically well with new coffee machines? Some high-quality coffee. I hear that Iron and Fire have some of the best coffee going. Now that I have a new coffee machine, I actually think that having other pieces of equipment like a milk frother just makes it look like you know what you’re doing, even if you don’t. With this being said, when you start learning how to make that perfect cup of coffee, it might make all the difference when it comes to the tools you use. After doing my research and coming across sites like neptune coffee, I’m considering getting one of these. Considering I am trying to improve my coffee making skills, maybe this could be the solution to create the best coffee ever. I won’t know if I don’t try! She’s gotten even better at coffee making since she went to work at Horizon Books because she sometimes has to man the espresso machine. She can even make latte art – you know, panda faces in the foam kind of thing. She’s tried to teach me to make coffee and I’m getting better. Which gives me hope. Which also might give you hope.

Because making coffee is a lot like writing. If you study the craft of successful coffee-makers, if you work at the formula and fine-tune your machinery, you can produce something others will find worth consuming.

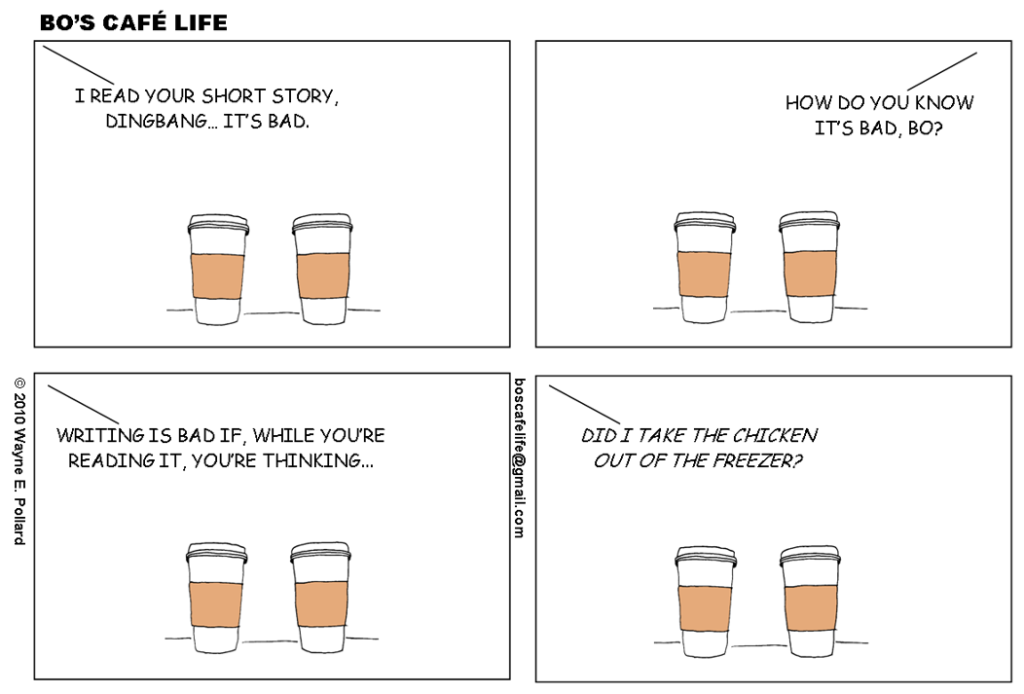

So, in an effort to help you brew a better manuscript, I am going to offer some silly but effective coffee metaphors. And thanks to Bo’s Cafe Life, one of my fave blogs about the writing life as seen through the eyes — and ink pen — of talented cartoonist Wayne Pollard. CLICK HERE to see more of Wayne’s work. His blog is worth a regular visit!

Muddy Coffee

A common problem in manuscripts is lack of simple clarity in the writing. Who is doing what where? Have you clouded your action with too many side trips into description or backstory? Have you told the reader where the hero is in time and geography? Can we understand what he/she is doing? Do we know who is talking? (ie, is your dialogue attribution signage clear?) Can we “see” the action?

“I have trouble writing if I can’t picture how things are going to look. –Robert Kirkman

Robust Coffee

Pay attention to your mood, imagery, description. You can put your cup of coffee in front of someone but if they can’t taste it, smell it or feel its warmth, they will pour it down the drain. One problem we often see in manuscripts is anemic or even non-existent description. No, you don’t want to lard up your beginning pages with TOO much of this. But some well-honed description can go a long way to seducing a reader into your story.

Deep Dark Coffee

This is what we call “internal dialogue.” This is a narrative device whereby you let the reader into your characters thoughts, memories and feelings. Internal monologue can and should happen anywhere but it should complement whatever is happening in action.

In high action: Use shorter, faster, high impact words. You are inside the POV character’s brain. The words you choose to describe what he/she is feeling should amplify the mood of the scene. In slower scenes: You can use longer sentences, more thoughtful, calmer tone, softer words and a slow pace. Using a slower style in an action scene will end up giving you something like this:

He stood over the man, knife in hand. He wondered now if he could actually stab him, if he had the guts to thrust the blade into flesh. He remembered that hot day in July twenty-three ago, sitting at his mother’s knee, looking up to her with the kind of hope only a young boy could hold. Will Daddy be home soon, mama? His father had taught him…

The above cup of coffee should be tossed down the sink.

Distinctive Coffee

Dialogue is the lifeblood of your fictional brew. Keep it clean, effective and do not waste your precious beans on over brewing it or making more than your reader can drink.

Burnt Coffee

Did you “phone in” the last few chapters because you were just sick and tired of your own story or your own characters? Did you lose control of your pacing somewhere earlier in the story and as you raced toward the end and now you have too many loose ends to tie up? The ending of a book is almost as important as the opening. We talk here often about how crucial it is to concoct a grabber first couple pages. But a finely crafted, well-planned slam bang ending is also important. You have to leave the reader with a feeling of satisfaction (which isn’t the same as a “happy” ending) and a feeling that the ending has been well-earned.

Stale Coffee

Maintaining suspense is critical to crime fiction. But even if you write kid lit or historical romances, you still need to keep the reader guessing. Does what you brew taste stale? Does it make you hunger for more? Does it go cold too quickly? And pay hard attention to the “second act” of your story, what we call the “muddy middle.” This is where most stories go off the rails. Suspense does not have to a stalker lurking in the shadows. It can be as subtle as a long awaited kiss or as dramatic as a killer jumping out of the bushes. This is probably the hardest task for writers – keeping the coffee at just the right temperature and rich taste for the duration of the pot.

Keeping Your Coffee Great For 400 Pages

• Stay focused

• Occasionally re-read your how-to books to help recognize where you’ve backslid. (Sample your own coffee every once and while)

• Read good writers to break through writer’s block and ignite your creativity. (Try other people’s coffee.)

• Read bad writers to jump-start confidence and rev up determination. (Pick up a cheap cup of coffee occasionally and force it down.)

• Continue to seek out and accept feedback as a professional.

• Know when a scene or the book is FINISHED. There’s only so much sugar, cream of cinnamon you add to a cup of coffee.

Cutting Your Chances of Your Coffee Being Rejected

Before she went into retirement, super-agent Miss Snark blogged often about what she looked for in manuscripts that crossed her desk. She said it always boiled down to three simple questions she asked of every submission she read:

- Do you write well? (Is your coffee hot and finely brewed?)

- Is your book premise fresh and interesting? (Have you cultivated a new bean?)

- Is your voice compelling? (Do you have a fresh way to serve your coffee, or have you added a unique flavor?)

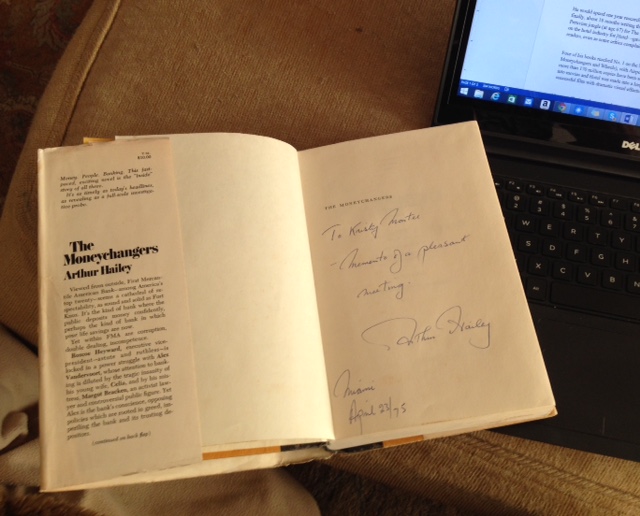

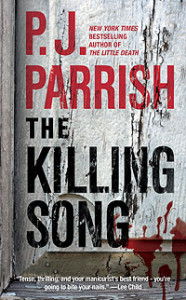

I hope you’ll allow me a moment of blatant self promotion. Our new book SHE’S NOT THERE is finally out! The South Florida Sun-Sentinel critic Oline Cogdill calls it “captivating.” Author Hank Phillippi Ryan, calls it “Taut, tense, and twisty—this turn-the-pages-as-fast-as-you-can thriller is relentlessly suspenseful.” Here’s the LINK.

Postscript: I am on vacation in France’s Loire Valley this month and I have wifi at my little cottage. But given the proximity of wineries, patisseries, and good books waiting to be read, I might not be here to comment. I promise to try to check in! But in the meantime, go get that second cup of joe (or a glass of Sancerre? Hey, it’s apero hour somewhere!) and watch this little video Kelly made on how to become an overnight success in this writing biz. Watch for your cameo, Nancy Cohen!