Recently Kay DiBianca and I talked about the elements of a cozy mystery, which you can read here if you missed it the first time.

I thought it would be worthwhile to dive into the TKZ archives to look at mystery elements in general. I love studying story elements and structure, especially with mysteries.

Red Herrings are an important part of mysteries, and Kathryn Lilley has a terrific summation of what makes some good and some stink. Foreshadowing is important in fiction in general, but I’d argue that it’s essential in mystery fiction. Jodie Renner looks at ways to use foreshadowing which can work well in setting up and revealing a mystery. Finally, how do you come up with a mystery? Where do you begin? Cozy mystery author Nancy Cohen shares her methodology, which also does a fine job of giving a rundown of the core elements of a mystery.

As always, the full posts are date-linked at the bottom of their respective excerpts.

What makes some red herrings good, and others stink like yesterday’s…well, red herring?

Camouflage

Red herrings shouldn’t scream, “Hey, I’m a clue!” from the rooftops. Readers are smart, and they’ll be working to solve the mystery as they go. They don’t need you to stomp on ’em. The subtlety rule applies to all clues, not just to red herrings.

A fish before dying

You can plant a red herring before your victim turns up dead, right at the beginning of your story. At that point, your reader doesn’t even know who is going to get killed, much less whodunnit.

Dead fish need not apply

All clues, including red herrings, must serve to move your story forward. Don’t use your red herrings only as a way to throw the reader off. Make them integral to your plot or character-building.

Two-faced fish

In some of my books, I wasn’t sure who the villain was until very near the end of the writing process. I write all the clues so that any of them can be red herrings or valid clues, depending on the ending.

Kathryn Lilley—August 4, 2009

Here are some ways you can foreshadow events or revelations in your story:

– Show a pre-scene or mini-example of what happens in a big way later, for example:

The roads are icy and the car starts to skid but the driver manages to get it under control and continues driving, a little shaken and nervous. This initial near-miss plants worry in the reader’s mind. Then later a truck comes barreling toward him and…

– The protagonist overhears snippets of conversation or gossip and tries to piece it all together, but it doesn’t all make sense until later.

– Hint at shameful secrets or painful memories your protagonist has been hiding, trying to forget about.

– Something on the news warns of possible danger – a storm brewing, a convict who’s escaped from prison, a killer on the loose, a series of bank robberies, etc.

– Your main character notices and wonders about other characters’ unusual or suspicious actions, reactions, tone of voice, facial expressions, or body language.Another character is acting evasive or looks preoccupied, nervous, apprehensive, or tense.

– Show us the protagonist’s inner fears or suspicions. Then the readers start worrying that what the character is anxious about may happen.

– Use setting details and word choices to create an ominous mood. A storm is brewing, or fog or a snowstorm makes it impossible to see any distance ahead, or…?

– The protagonist or a loved one has a disturbing dream or premonition.

– A fortune teller or horoscope foretells trouble ahead.

– Make the ordinary seem ominous, or plant something out of place in a scene.Zoom in on an otherwise benign object, like that bicycle lying in the sidewalk, the single child’s shoe in the alley, the half-eaten breakfast, etc., to create a sense of unease.

– Use objects: your character is looking for something in a drawer and pushes aside a loaded gun. Or a knife, scissors, or other dangerous object or poisonous substance is lying around within reach of children or an assailant.

– Use symbolism, like a broken mirror, a dead bird, a lost kitten, or…

Jodie Renner—January 27, 2014

How do you formulate a traditional murder mystery plot? Do you start with the victim? The villain? Or do you select an evocative location or a controversial issue and start there?

I’ll clue you in to my methodology. This might work differently for you and is by no means a comprehensive list. But these are the elements I consider when planning a mystery. It’s part of what I call the Discovery phase of writing.

Book Title

Do you title your story before or after you write the book? I prefer to have a title up front. Sometimes, this dictates what I have to do next. For example, in Murder by Manicure, I had a title and no plot.

This had been part of a three-book contract, and all of a sudden my publisher wanted a synopsis. I had to come up with an idea that incorporated the title. Someone had to die either while getting a manicure or as a result of one. I face this same quandary now. I have the title, and I have to suit the crime to this situation. That brings us to the next element.

The Crime Scene

Do you begin with the victim or the villain? In a psychological suspense story, you might begin with the villain and why he became that way. The focus would be on how he turned to the dark side and what motivates him now. Then in comes your hero who has to figure out a way to stop him while delving into his psyche at the same time.

My plots center around the victim. Who is this person? Where do they die? How do they die? Once I figure out the Howdunit, I’ll move on to the next factor.

The Victim

What made this person a target? Here we might learn about their job and personal relationships. Was this person loved without a single blemish in his past? Or did other people have reason to resent him? What might have happened in his past to lead up to this moment? And what did he do to trigger the killer at this point in time? What could he be involved in that you as a writer might want to research?

The Cause

This is the passionate belief that underlies your story. It’s what gets me excited about a book, because I can learn something new and feel strongly about an issue while weaving it into my tale. In Hanging by a Hair, I deal with condo associations and their strict rules. I also touch upon Preppers and the extremes they go to in their survivalist beliefs. Or perhaps my theme is really about family unity, and how Marla strives to bring peace to the neighborhood so she can resume a normal family life. In my current plot, I finally hit upon The Cause. Now the elements are starting to come together. It’s exciting when this happens. And that brings us to the next factor.

The Suspects

Who has the motive, means and opportunity to have committed the crime? Does every one of your suspects have a viable motive? If so, whodunit? And why now? How can you relate these people to each other? This is the fun part, where the relationships build and the plot begins to coalesce in your mind. Character profiles might help at this stage, so you have a better concept of each person before they step on stage. Seek out photos if necessary and do any research you might need before you get started writing. What does The Cause mean to these people? Is it the reason why the victim had to die? Or is it the glue the sleuth will use to put the pieces together?

Nancy Cohen—August 13, 2014

***

- What makes a good red herring for you, both as a writer and a reader? How do you avoid an obvious red herring?

- What’s a favorite way you like to foreshadow?

- How do you come up with a mystery? What inspires you?

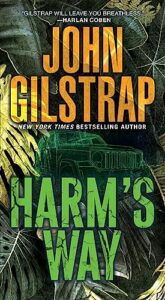

First things first. As I write this, it’s Book Launch Day! Harm’s Way, the 15th entry in my Jonathan Grave thriller series drops today. In this story, Jonathan is summoned by FBI Director Irene Rivers to rescue someone special from the grips of a drug cartel that has taken a group of missionaries hostage in Venezuela. Once the team arrives, however, they discover trouble far more horrifying than a standard hostage rescue. When the first book in the series appeared in 2009, I never would have thought it would have the kind of legs that it has.

First things first. As I write this, it’s Book Launch Day! Harm’s Way, the 15th entry in my Jonathan Grave thriller series drops today. In this story, Jonathan is summoned by FBI Director Irene Rivers to rescue someone special from the grips of a drug cartel that has taken a group of missionaries hostage in Venezuela. Once the team arrives, however, they discover trouble far more horrifying than a standard hostage rescue. When the first book in the series appeared in 2009, I never would have thought it would have the kind of legs that it has.

We often talk about a character’s backstory, including a “wound” that haunts as a “ghost” in the present. It’s a solid device, giving a character interesting and mysterious subtext at the beginning. The wound is revealed later as an explanation. (Think of Rick in Casablanca. “I stick my neck out for nobody” and his casual using of women. The wound of Ilsa’s “betrayal” doesn’t become clear until the midpoint).

We often talk about a character’s backstory, including a “wound” that haunts as a “ghost” in the present. It’s a solid device, giving a character interesting and mysterious subtext at the beginning. The wound is revealed later as an explanation. (Think of Rick in Casablanca. “I stick my neck out for nobody” and his casual using of women. The wound of Ilsa’s “betrayal” doesn’t become clear until the midpoint).