“The average detective story is probably no worse than the average novel, but you never see the average novel. It doesn’t get published. The average — or only slightly above average — detective story does…. Whereas the good novel is not at all the same kind of book as the bad novel. It is about entirely different things. But the good detective story and the bad detective story are about exactly the same things, and they are about them in very much the same way.” — Raymond Chandler

By PJ Parrish

Okay, it’s time to talk about the F-word.

But before we do, I have to back up a little and first talk about ballet.

Back in my newspaper days, I spent 18 years as a dance critic. I was privileged to see every great ballet company in the world, and interview wonderful dancers. I also took a lot of classes, starting when I was a tubby little 12-year-old to around 35 when I finally hung up the toe shoes. I didn’t know it at the time, but ballet was really good training for becoming a crime novelist. Because both are based on finding magic within the formula.

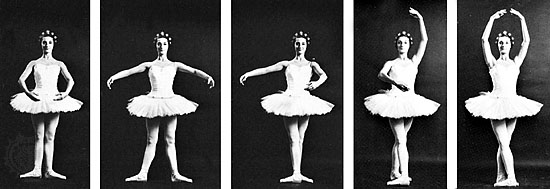

A quick primer for all you ballet-adverse types out there. Bear with me, because you will need this when I get to Raymond Chandler:

Everything in ballet can be boiled down to five positions. There are only five ways to position your feet, five ways to hold your arms. But…

Everything in ballet -– from the classical precision of Swan Lake (1875) through the sassy sweep of Twyla Tharp’s Nine Sinatra Songs (1982) — flows out of this. Think about that for a second: Within one strict formula can be found myriad unique opportunities for self-expression.

One of my favorite ballets is George Balanchine’s Serenade. Balanchine was a genius. He sort of did for dance what Raymond Chandler did for the detective novel, building a bridge between the 19th and 20th centuries, finding new permutations within the old formula, and changing everything that came after forever. Serenade was the Rosetta Stone for a new kind of dancer. Philip Marlowe, likewise, held the DNA for a new kind of hero.

The opening of Serenade is breathtaking in its simplicity and promise. Seventeen dancers stand motionless on stage, one arm raised, feet parallel. Then, slowly, their arms come down together in first position, and a beat later, their feet turn out. With that one motion, they mutate from mere women into dancers, standing in the first position from which all movement flows. Go watch it and come back. It will only take 53 seconds.

Now, here’s the opening of Chandler’s The Big Sleep.

It was about eleven o’clock in the morning, mid October, with the sun not shining and a look of hard wet rain in the clearness of the foothills. I was wearing my powder-blue suit, with dark blue shirt, tie and display handkerchief, black brogues, black wool socks with dark blue clocks on them. I was neat, clean, shaved and sober, and I didn’t care who knew it. I was everything the well-dressed private detective ought to be. I was calling on four million dollars.

Like Serenade, this opening is breathtaking in its simplicity and promise. Right away, we know we are beginning a journey with a very special guide. And oh, those telling details. Who but a man who’s been on too many benders would point out that he was sober this time? And that last line? A lesser writer would have been content with: “I was going to see a rich guy.” Such delicious sarcasm and attitude!

Both Serenade and The Big Sleep are exemplars of two master artists working within the confines of their genres even as they explore and expand the formula.

So back to the F-word. Let’s talk about formula. I think it’s become a dirty word in our crime writing world, tossed around as a pejorative by folks who want to put us in our place. Some want to draw distinctions between genre fiction and literature. (“Her novel transcends the blah-blah-yada-yada.”) And some, even within our own circle, want to diminish writers who hew too closely to the bones. (“He’s working the tired old formula.”)

Years ago, I was on a panel about the future of the PI novel. There was a strange undercurrent to it, like it was put on the program almost as an apologia. It was like the conference organizers were accommodating the private eye novelist as the goofy cousin you seat at the kid’s table at Thanksgiving. Chandler himself, in a great interview with Ian Fleming put it this way: “In America, a thriller, a mystery writer as we call them, is slightly below the salt.” (Click here to hear the entire fascinating exchange.)

But I think the PI formula — and indeed, the entire crime fiction blueprint — has much to recommend it. Mainly because, as with ballet, once you master its fundamentals, once you understand the underlying structure and learn the basic “rules,” you are freed to swing for the fences.

I guess we should stop and take a hard look at that word “rules.” It’s a scary word because some of us think we don’t know the rules and others think the rules are there only to be broken. There have been a lot of rules doled out over the years regarding crime fiction. S.S. Van Dine’s “Twenty Rules for Writing Detective Stories,” written in 1928, might be the most famous. Van Dine prefaced his rules thusly:

The detective story is a kind of intellectual game. It is more—it is a sporting event. And for the writing of detective stories there are very definite laws—unwritten, perhaps, but nonetheless binding; and every respectable and self-respecting concocter of literary mysteries lives up to them.

My favorite Van Dine-ism: “There simply must be a corpse in a detective novel, and the deader the corpse the better.”

A year later, Ronald Knox wrote “The Ten Rules of Detective Fiction” My favorite Knox sin: “No Chinaman must figure into the story.”

T.S. Eliot was a big fan of detective novels, and was compelled to publish his own set of rules, in 1927 in his literary magazine The Criterion:

- The story must not rely upon elaborate and incredible disguises.

- The criminal’s motives should be fairly predictable. “No theft, for instance, should be due to kleptomania (even if there is such a thing).”

- The solution should not involve the supernatural or “mysterious and preposterous discoveries made by lonely scientists.

- Elaborate and bizarre machinery is an irrelevance. Detective writers of austere and classical tendencies will abhor it.

- The detective should be highly intelligent but not superhuman. We should be able to follow his inferences and almost, but not quite, make them with him.

Even Raymond Chandler himself couldn’t resist laying some laws. Here are his Ten Commandments For the Detective Novel:

- It must be credibly motivated, both as to the original situation and the dénouement.

- It must be technically sound as to the methods of murder and detection.

- It must be realistic in character, setting and atmosphere. It must be about real people in a real world.

- It must have a sound story value apart from the mystery element: i.e., the investigation itself must be an adventure worth reading.

- It must have enough essential simplicity to be explained easily when the time comes.

- It must baffle a reasonably intelligent reader.

- The solution must seem inevitable once revealed.

- It must not try to do everything at once. If it is a puzzle story operating in a rather cool, reasonable atmosphere, it cannot also be a violent adventure or a passionate romance.

- It must punish the criminal in one way or another, not necessarily by operation of the law….If the detective fails to resolve the consequences of the crime, the story is an unresolved chord and leaves irritation behind it.

- It must be honest with the reader.

Now of course you can see that Chandler’s “rules” are more in tune with our own modern sensibilities. He, like ballet’s Balanchine, pointed the way to the future. He, like Balanchine, took the old formula and made it new. Which is why we still read him today and we don’t read S.S. Van Dine or Ronald Knox.

It’s often said that we writers only recycle the same plots over and over. There are, in fact, only seven stories in the world, according to the writer Sir Arthur Thomas Quiller-Couch. Here they are:

- man against man

- man against nature

- man against himself

- man against God

- man against society

- man caught in the middle

- man and woman

So Romeo and Juliet is reborn as West Side Story. Moby Dick resurfaces as Jaws. King Lear becomes A Thousand Acres in the hands of Jane Smiley. And don’t get me started on what Bram Stoker unleashed on us.

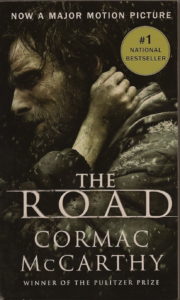

This post was inspired by Larry Brook’s post here last week on concept vs premise. Go back and read it if you haven’t already. As I said in my comment there, the current hit movie The Martian is really just an old plot, one Sir Arthur himself would recognize as Man vs Nature but transported to Mars. Before The Martian, we had Robinson Crusoe, The Swiss Family Robinson, PD James’s Children of Men, Laura Ingalls Wilder’s The Long Winter, Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, and Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend, which was recycled into the cheesy Charleston Heston movie Omega Man.

Formulas are not, in themselves, bad things. And given the long and glorious history of the crime novel, it is something we should honor, not disdain. The “trick” for us is to find within the universal human experience, fresh things to say about our own times and situations.

The ballet Serenade ends on a mournful note, a man borne off by a female dancer who, to my mind, is a symbolic angel.

And then, there is the equally elegiac ending paragraphs of The Big Sleep.

I went quickly away from her down the room and out and down the tiled staircase to the front hall. I didn’t see anybody when I left. I found my hat alone this time. Outside, the bright gardens had a haunted look, as though small wild eyes were watching me from behind the bushes, as though the sunshine itself had a mysterious something in its light. I got into my car and drove off down the hill.

What did it matter where you lay once you were dead? In a dirty sump or in a marble tower on top of a high hill? You were dead, you were sleeping the big sleep, you were not bothered by things like that. Oil and water were the same as wind and air to you. You just slept the big sleep, not caring about the nastiness of how you died or where you fell. Me, I was part of the nastiness now. Far more a part of it than Rusty Regan was. But the old man didn’t have to be. He could lie quiet in his canopied bed, with his bloodless hands folded on the sheet, waiting. His heart was a brief, uncertain murmur. His thoughts were as gray as ashes. And in a little while he too, like Rusty Regan, would be sleeping the big sleep.

On the way downtown I stopped at a bar and had a couple of double Scotches. They didn’t do me any good. All they did was make me think of Silver Wig, and I never saw her again.

There is nothing new. Just new ways of making us feel.

By the time we travelled to Bath I was ready for the next few gems, including a reference to a potential character in the Bath abbey and a visit to a charming town in the Cotswolds that had a small medieval church and graveyard that could totally be used in a future book.

By the time we travelled to Bath I was ready for the next few gems, including a reference to a potential character in the Bath abbey and a visit to a charming town in the Cotswolds that had a small medieval church and graveyard that could totally be used in a future book.