“Fiction is the truth inside the lie.” — Stephen King

By PJ Parrish

We all tell lies. Some of us, like politicians, make it into an art form. But most of us just bump along through life moving along the lie spectrum from the little-white variety (“Of course you’re not too old to wear leopard leggings!”) to the whopper (“I’m a natural athlete.” – Lance Armstrong.)

We all lie. To prove it, I’ll start with a little Truth or Dare. Here are five statements about me. Which ones are lies? (Answers in a little bit.)

- When I was 47, I was in the Miami City Ballet’s production of “The Nutcracker” directed by the acclaimed dancer Edward Villella.

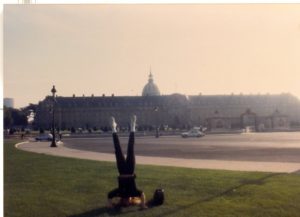

- I once stood on my head at Les Invalides, the place in Paris where Napoleon is entombed.

- I interviewed Michael Jordan in the Bulls locker room for a story about “hang time.”

- I was invited to a party on the royal yacht Britannia where Queen Elizabeth asked me what I did for a living.

- Telly Savalas let me lick his lollipop.

Now, we writers are born liars. We have to be to create fiction. And the better we are at lying, the better our books tend to be. Okay, let’s elevate the conversation and call it “suspension of disbelief” instead of lying. We hear that phrase all the time, here at The Kill Zone, in reviews, and on panels at writers conferences. But what does “suspension of disbelief” really mean?

All fiction requires some suspension of disbelief, right from the get-go. We crack open a novel knowing what we are about to read is not really true. We strike a bargain of sorts with the author — we are willing to believe his story’s premise before we read even the first word. But that is a mere promise. The hard part for us, the writers, comes in maintaining that suspension of disbelief over the course of an entire story.

If you’re writing fantasy, horror, or science fiction, “suspension of disbelief” is a basic ingredient of the craft stew. In these unreal worlds, vampires fall in love, Harry Potter breaks the laws of physics and Virgin Air has daily flights through wormholes to Vega. That’s cool because these worlds are meant to be very different from our own. But what about the “real worlds” of crime fiction? What lies can we get away with in our quest for dramatic impact?

Time out for the answers to my true lies:

- True, I was in The Nutcracker at age 47. I was only in Act I but when it was over, I wanted to do it all over again. The experience gave me a taste of the narcotic all performers feel.

- True. Here’s the picture at left to prove it.

- True, I interviewed Michael Jordan. It was on the occasion of Jordan’s comeback (first or second one, I can’t recall). Most the Bulls were nekkid or almost so. Mike was resplendent in a white suit. He was holding court surrounded by sycophantic sportswriters who all tried to elbow me aside. I was the ballet critic and talked to Jordan about the similarities between hang time and ballone (how dancers seem to float in the air). Jordan was fascinated by this but wasn’t happy when I told him Spud Webb was recorded by a physics professor as having the longest hang time in the NBA.

- True. I was sent by my newspaper to cover the opening of the Bahamian parliament in 1977 and got to meet Her Majesty on the yacht. Liz did, indeed, ask me what I did for a living. I don’t remember what I said because I was absolutely impaled by her icy blue eyes. For the record, Liz is even shorter than I am. But her husband Phil was very tall, very gregarious, and had a little too much to drink.

- Not true. I did get to interview Savalas. He gave me a big hug but did not let me lick his lolly.

Back to the issue at hand. Now, I can’t talk too authoritatively about fantasy, sci-fi or horror because I am not well-read in those genres. But I’ve read hundreds of crime books (and written a few), and I think some writers of crime fiction think “suspension of disbelief” gives them license to write whatever they want — damn reality or fact.

Which is a lie.

Crime fiction, in its way, is harder to write than sci-fi or fantasy when it comes to how much we can lie. That’s because while we crime writers are tethered to the realities of police protocol, forensics, legal procedures, we have to bend these truths in service of good plotting and dramatic tension.

I once heard a famous crime writer guy on a panel say that all crime fiction had to have verisimilitude. I used to think that was just a ten-dollar word for truth. But then I realized what he was talking about was not truth, but a conjured version of it.

Definition: Verisimilitude /ˌvɛrɪsɪˈmɪlɪtjuːd/ is the “life-likeness” or believability of a work of fiction. The word comes from Latin: verum meaning truth and similis meaning similar.

Verisimilitude is not truth. Verisimilitude is the “similar” to “truth.” So the our goal as crime writers should be creating a credibility that reflects the realism of human life. It’s as if, when we create our fictional crime worlds, we are asking our readers to view them through a mirror…not directly on, but by a reflection, slightly altered for dramatic effect.

So why do some crime books feel so wrong? Why do some characters feel so false? When does good suspension of disbelief slide into the muck of lazy writing? Here are some ways I think this happens. (You guys please add your own!)

Characters do outrageous things. Yes, a character can go rogue or surprise. But their actions must arise from the realities of their nature as you have laid them out. Have you ever read a scene and you find yourself shaking your head and saying, “I just don’t believe the hero would do this.” That’s the writer not laying down the psychological foundation for the character to act a certain way.

Characters do stupid things. Yes, it’s good to have your hero go mano-a-mano with the bad guy in the climax, but you have to set it up. I read a thriller a while back where the female detective, fresh off a hot date, goes up into a creepy old house after a serial killer — in her heels and without a gun. This is a variation of the dumb-blonde-goes-into-the basement thing.

But…but…Clarice Starling went down into the basement after Jame Gumm! Yeah, but Thomas Harris set it up brilliantly by having her show up at the wrong house and then, when she realizes the killer is there, she goes into the basement after him because she knows Kathryn is still alive and the clock is ticking. (Harris establishes this by telling us Buffalo Bill keeps his victims alive so he can starve them and loosen their skin).

Don’t put your protag in peril by making them stupid or inept. Do it by creating a crafty set-up. Shape the action leading up to your end-game situations so your confrontation is believable enough for reader to buy into.

Dumb police procedure, legal things, and forensics. You have to be in the ballpark with this stuff. In real life, cases drag on forever, test results take weeks to come back from the lab, court cases drone on without Perry Mason moments. But that is boring in books. So we writers have to condense time, inflate authority, cross boundaries, and yes, even make some stuff up — yet still make it feel true. This is not easy. It helps if you have some experts to fall back on. I’ve called on attorney friends for legal questions, on Dr. Doug Lyle to help me fudge forensics, and I have a retired state police captain on speed dial who keeps me honest but appreciates the fact I have to bend the truth for drama.

One of my favorite crime novelists, Val McDermid, has written two terrific non-fiction books on forensics. She has this to say on the subject: “By and large, I try to be pretty accurate in how I write about the science. But sometimes you do need to make changes for dramatic necessity – for instance, squeezing a test that would take three weeks into two days. That’s the area where we mostly fall down – compressing time frames.” Click here to read more.

Getting the police stuff right is really important to me. My favorite crime movie is Zodiac, the fictionalized story of the real Zodiac killer who terrorized northern California for a decade. The movie shows the drudgery, time-dragging reality, and soul-destroying futility of police work, yet remains dramatically riveting. And the case never got solved.

I can get anal about cop details. I’m writing a chapter this week where Louis is tracing the steps of a suspect that leads him to an apartment where he sees — surprise! — a crime scene premises seal on the door. Louis learns from the owner that a woman was murdered inside a week ago. The local cops have cleared the scene. Can Louis go inside? Can he seize evidence that he thinks is relevant to the OTHER case he is pursuing? I emailed my police captain, laying out this scenario. He wrote back (in part!):

“The Fourth Amendment only protects the “person’s” right from governmental action – the illegal search and seizure. Louis is “government” but the person whose rights might be violated is no longer a person — she is dead — so Louis could go in and seize her property and because she is not around to be prosecuted for the “evidence” he may seize then it is not a Fourth Amendment issue. Second, the owner has permission and the right to enter the apartment so if Louis asks and the owner gives permission for Louis to enter with him then he has the right to be there. Once there anything that he sees in plain sight that he thinks is evidence he could seize.”

Problem solved. Louis gets in, finds what he needs, plot moves forward. In reality, things would play out differently, my police captain said. But with this, I am in the ballpark of suspended disbelief.

Lost and Befuddled Amateurs. So what if your protagonist is not a cop or detective? What if they have no logical reason to get involved with the crime? This is a tough one, and one reason we get so many protags who are lawyers and journalists, as these jobs can dovetail with the crime world. Now, if you wrote cozies, your readers allow for a suspension of disbelief by default, buying into the idea of the civilian-savior. But you still have to set things up so the protag isn’t just an idle observer (yawn) but an active participant (Yay!).

I have been working with a writer through Mystery Writers of America’s mentoring program. Her book features an engaging protag who works in a florist shop. While delivering flowers to a rich matron, the protag finds her dead body in the foyer. Cops are called, of course, but the writer had a problem: She couldn’t justify a flower shop employee having access to the case — or even a reason to solve it. The scenes weren’t believable because the cops would never let a civilian on scene let alone into the case. But through tough rewriting and hard rethinking of her protag’s motivations, the writer solved the problem by making the protag a disgraced journalist who is desperate to clear her reputation.

She’s learned the lesson. Yes, you can lie. But it better ring true.